Art & Exhibitions

How Artist Renzo Martens Aims to Funnel Western Capital Back to the Plantation

Chocolate sculptures have changed workers' lives.

Chocolate sculptures have changed workers' lives.

Brian Boucher

What if a gallery show in Berlin or Amsterdam, with sculptures selling for thousands of Euros, could benefit African workers who live on salaries in the range of a dollar a day?

That’s been the recent project of Dutch artist Renzo Martens, one that comes in for scrutiny in the first show of 2017 at New York’s SculptureCenter. It’s the debut American exhibition for works by a group of Congolese sculptors that are part of a project to send much-needed money back to African laborers.

The members of the Cercle d’Art des Travailleurs de Plantation Congolaise (CATPC, or Congolese Plantation Workers’ Art League) create sculptures out of chocolate, which is made with cacao, a crop that has been the subject of much scrutiny for its impact on the environment, and for controversial labor conditions. A number of those works will go on view at SculptureCenter, in Long Island City, Queens, in a show organized by the institution’s curator, Ruba Katrib.

View of research center (still under construction), 2016. Photo Léonard Pongo, courtesy SculptureCenter.

Organized as a group with the help of Dutch artist Renzo Martens and his Institute for Human Activities (IHA), the CATPC consists of workers on a plantation owned by the multinational consumer goods giant Unilever.

Martens’s inspiration was to train a number of plantation workers to be artists, whose works would be sold at Martens’s galleries in Berlin and Amsterdam. To date, the workers have received about $35,000, says Martens, which they’ve largely plowed into their own small gardens.

“That amount represents something like 15 yearly salaries for all the members of the group combined,” Martens told artnet News in a recent Skype conversation.

Jérémie Mabiala reflecting on his work, 2015. Courtesy SculptureCenter.

The plantation workers involved in the group include Djonga Bismar, Mathieu Kilapi Kasiama, Cedrick Tamasala, Mbuku Kimpala, Mananga Kibuila, Jérémie Mabiala, Emery Mohamba, and Thomas Leba. Working with them are ecologist Rene Ngongo and the Kinshasa-based artists Michel Ekeba, Eléonore Hellio, and Mega Mingiedi.

“I had never seen, touched, or tasted chocolate before having made sculptures out of Congolese cacao,” CATPC artist Daniel Manenga said in an email. “I did it for the first time in my life thanks to CATPC. But above all now I can send my sculptures to people I will never meet, and to whom I will never be able to explain under which conditions we live here.”

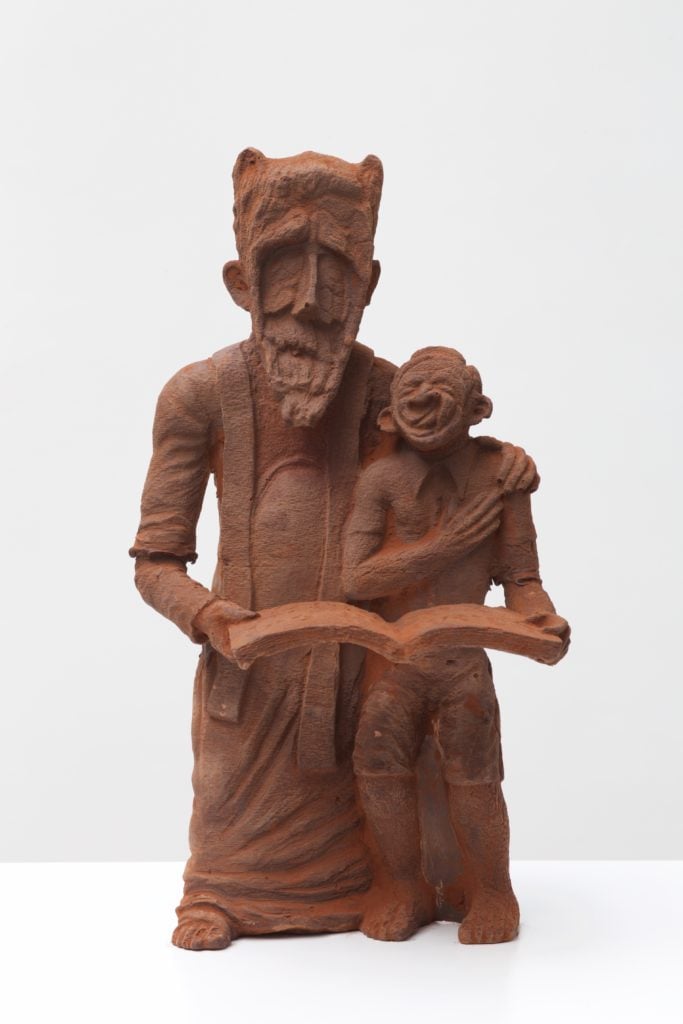

Martens professes to being deeply impressed with the artists’ works, which take the form of portraits, allegorical scenes, and even an image of a bespectacled art collector ensnared by a snake:

The amount of energy the members of CATPC put into these sculptures is unlike anything I see in art studios, because these works are their ticket out. These people put so much power into the sculptures. They know about being on the losing end of capitalism, and they know how to make beautiful works about that. They ask, how can we charge chocolate with our thoughts so that it puts us on the global map and provides us with an income?

Cedrick Tamasala, How My Grandfather Survived (2015). Courtesy SculptureCenter.

Martens is also at work securing donations by artists whose work has been supported by Unilever at Tate Modern, including figures like Anish Kapoor, Bruce Nauman, and Doris Salcedo, to an art museum taking shape on the original Unilever plantation, under design by Rem Koolhaas’s firm, OMA, and scheduled to open in March 2017.

By bringing works by those artists to Africa, Martens says, “We’re repatriating the fruits of the CATPC members’ labor.” He compares the art museum he’s starting to the African notion of the fetish, an object that aims to attract capital. In fact, it has already attracted a donation from Belgian artist Carsten Höller.

“Making sculptures and reaching such a wide audience is really an interesting way of discussing and denouncing inequality,” CATPC artist Tamasala told artnet News via email. “It’s a good way to draw attention to the situation of those most threatened by globalization.”

A desire to redirect global capitalism is at the heart of Martens’ project, on the philosophy that its effects are not only immoral but also impractical.

“This kind of thinking is necessary because the world needs to redress itself,” Martens said. The artist is known for provocative ideas; his 2008 documentary film Episode III: Enjoy Poverty suggested that a country like Congo could actually market its underdevelopment as its most valued natural resources, since this is what brings in international aid.

But in the meantime, out of the deprivation of the workers, the project has created a bright spot.

“My portrait is being eaten everywhere in the world,” said Mabiala via email, “and that makes me happy.”

The US debut exhibition of Cercle d’art des travailleurs des plantations Congolaise, at SculptureCenter, in Queens, will be on view January 28–March 27, 2017.