Reviews

Tate’s Robert Rauschenberg Survey Is a Brilliant and Much-Deserved Homage to a Unique Trailblazer

The retrospective, spanning six decades of work, is big, generous, and fascinating.

The retrospective, spanning six decades of work, is big, generous, and fascinating.

Lorena Muñoz-Alonso

The artistic career of the American artist Robert Rauschenberg was intensely prolific, multidisciplinary, promiscuous even in its unending curiosity and thirst for exciting collaborations. From tomorrow, December 1, the highlights of his six-decade-long career—which spans painting, sculpture, collage, assemblage, performance, printmaking, and costume and stage design—will be on display as part of a major exhibition at Tate Modern.

The show marks a momentous occasion in the study and understanding of Rauschenberg’s work. Organized in collaboration with New York’s MoMA, this is the artist’s first posthumous retrospective since he died in 2008, aged 82, and the most comprehensive survey of his work in well over 20 years. It has been curated by Achim Borchardt-Hume, director of exhibitions at Tate Modern, and Leah Dickerman, MoMA’s curator of painting and sculpture alongside Catherine Wood, Tate’s senior curator of performance.

The participation of Wood is, in fact, key. Despite Rauschenberg’s common reading as a (proto)Pop artist, his practice at large had a huge performative element, underpinning and intertwining seemingly disparate strands of work. As Wood said during the presentation of the exhibition, referring to Rauschenberg’s 1951 White Painting—which was used in Merce Cunningham and John Cage’s Theater Piece No. 1 as a backdrop—“even [his] more abstract works had a relation to the body.”

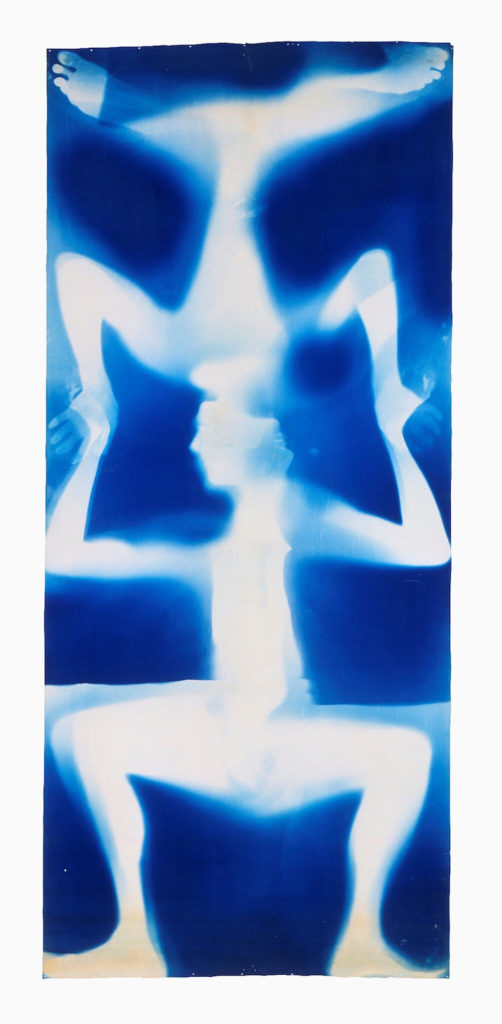

Robert Rauschenberg and Susan Weil, Untitled (Double Rauschenberg)(c. 1950). Photo ©Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York, courtesy Cy Twombly Foundation.

The hang of the exhibition is chronological and, in this case, it doesn’t read like an unimaginative museological convention but rather a riveting narrative device. In the first room, we see the early steps of Rauschenberg as an art student and a young artist, and the influence that his time at Black Mountain College, studying under Josef Albers, has had on his work (despite their many disagreements).

Here, we see the monoprints done in collaboration with his wife Susan Weil, the contours of their bodies outlined in a dazzling blue; his 22 The Lily White painting, one of the four extant pieces from his debut exhibition at the influential Betty Parsons Gallery in New York (both works 1950); the 1952 photo series Cy + Roman Steps (I-V), which symbolizes the increasing importance and influence of Cy Twombly in both his personal life and in his work. Also here is his seminal 1953 piece Erased de Kooning Drawing, a conceptual artwork avant la lettre.

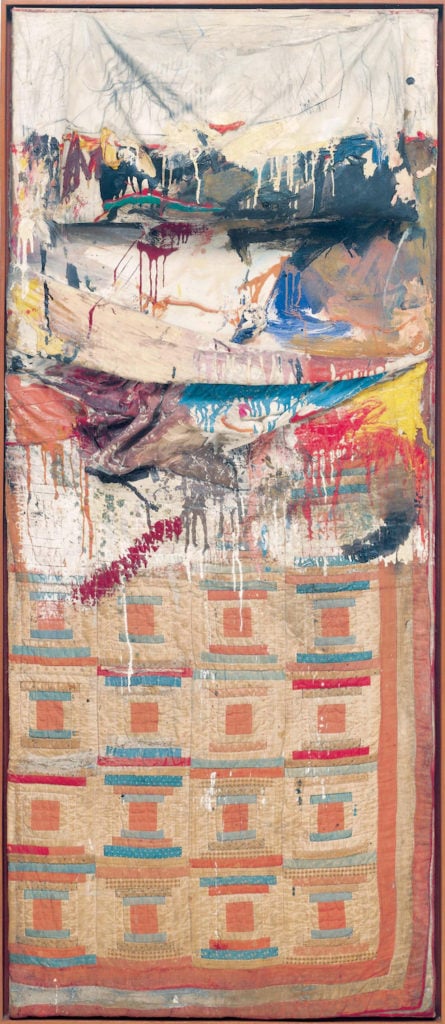

Robert Rauschenberg, Gold Standard (1964). Photograph courtesy Tate Photography. Glenstone Museum, Potomac, Maryland.

In the next two rooms, his Red Paintings—done in response to those who deemed his white and black monochromes as “anti-paintings,” and using the color he found most difficult to master—pave the way for his landmark Combines, a mix of painting and sculpture. The loans that Tate has secured here are nothing short of impressive.

Charlene for example, credited with being the key transitional piece from painting to the Combines, seldom leaves its home at Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum, yet here it is, near a projection of Minutiae (both works 1954), the ballet piece by Cunningham for which Rauschenberg devised a beautiful free standing sculpture-cum-backdrop. The piece, currently in a private collection, is sadly not here, but the performance documentation gives us a sense of both its presence and function.

Robert Rauschenberg, Bed (1955), the Museum of Modern Art, New York, gift of Leo Castelli in honor of Aldred H. Barr, Jr. Photo the Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence, ©Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York.

Also at Tate are the iconic and rarely loaned Combines Bed (1955) and Monogram (1955-59) which traveled from New York’s MoMA and Stockholm’s Moderna Museet, respectively. (To put things in perspective, this is the first time that Monogram travels to the UK in over 50 years). Protected behind vitrines and showing the patina of time, they nevertheless ooze the aura only masterpieces emit. They also look impossibly contemporary, still well ahead of the curve six decades after they were created.

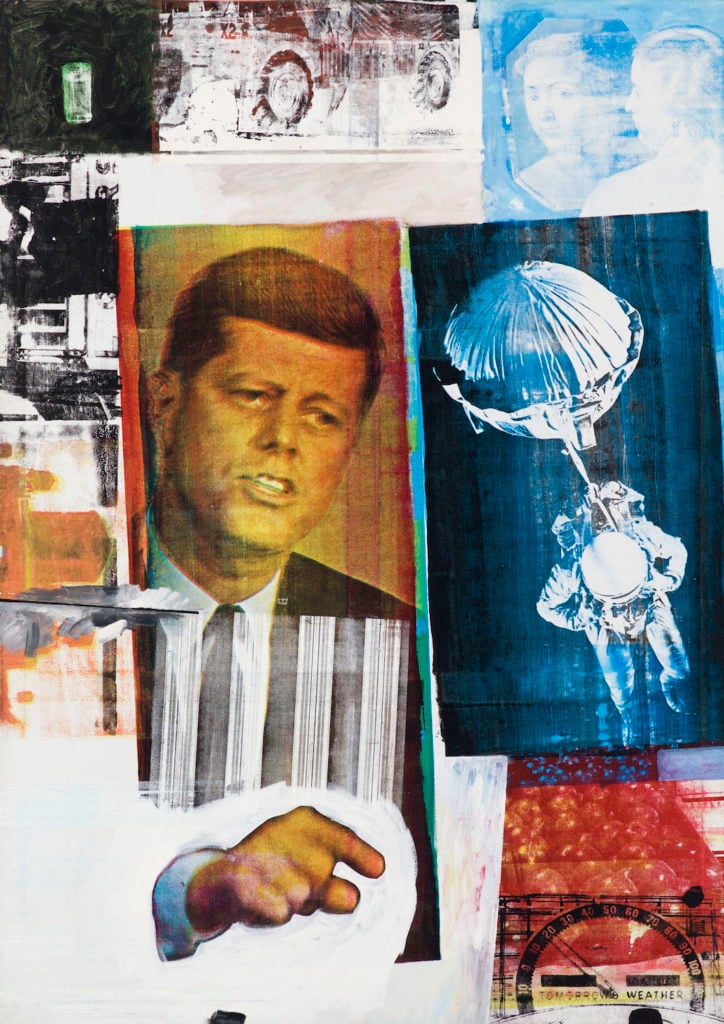

Up next, two rooms devoted to his transfer drawings and 1962 silkscreens, are perhaps the least compelling for this writer. The silkscreens particularly, coeval to those of Andy Warhol, are definitely Pop in their techniques, aesthetic, and themes (addressing subjects ranging from mass media to politics and the space race). That Retroactive II (1964), which incorporates an image of John F. Kennedy, is the show’s featured image, gracing the cover of the exhibition guide, its catalogue, and even its press materials, bears testimony to the major position that these Pop-infused works occupy in the general understanding of Rauschenberg’s work.

Robert Rauschenberg, Retroactive II (1964). The Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, partial gift of Stefan T. Edlis and H. Gael Neeson, ©Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York. Photo Nathan Keay ©MCA Chicago.

Yet, I can’t help thinking that another line of work, which he was simultaneously exploring in his prolific creative frenzy, is what made Rauschenberg the maverick innovator that he was—“one of art’s greatest trailblazers,” as Tate Modern’s director Francis Morris put it.

By that I mean his performance works, done in collaboration not just with his long-standing partners Cunningham and Cage, but also the members of the Judson Dance Theater (including Trisha Brown, Yvonne Rainer, and Steve Paxton), and the engineer Billy Klüver, with whom he organized 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering in 1966, followed by the creation of the nonprofit Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.)

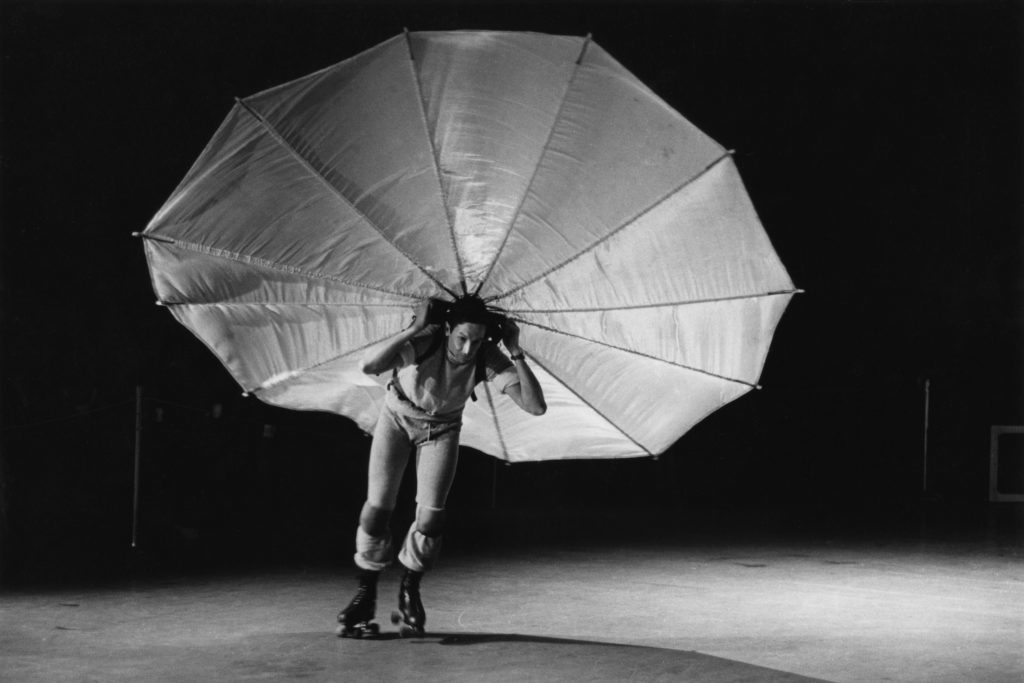

Rauschenberg’s role in this field was not limited to conceptualizing or designing sets; he become a performer, too, his body conquering the stage. The exhibition in fact shines a light on one fascinating hidden piece of art history: how and why Rauschenberg became an active performer. In 1963, after being accidentally credited as a choreographer in a program, he decided to go ahead with it, creating the piece Pelican, in which the artist and a companion roller-skated on stage, parachute-clad and circling around the dancer Carolyn Brown.

The sculptures he designed to be used on stage and interacted with are among his best works, as if the idea of use and function—of art-as-prop—enticed and excited the artist particularly. Minutiae, Oracle (1965), and the set created for Trisha Brown’s 1985 Lateral Pass particularly stand out in that regard.

Peter Moore, documentation of Robert Rauschenberg’s Pelican (1963).

Likewise, in the mid 1970s, during the period in which he worked intensely with textiles, fascinated by the properties of silk and other lightweight fabrics that he encountered during his travels across India, he created a brilliant series of sculptures as part of his Jammer series. Yet, never do these fabrics beguile and shine more than when Rauschenberg used them to create the costumes of Travelogue (1977), his reunion piece with Cunningham, where dancers wore fan-shaped structures attached to their bodies, dazzling the viewer as the stretch and hide those colorful shapes, like strange human wings.

Tate’s retrospective—which will travel to MoMA and SF MoMA next year—is big, generous, and fascinating, abundant both in aesthetic pleasures and joyful experiences and in scholarly research. It satisfies both the body and mind, and rewards close attention and repeated visits, so the small details—like the vitrines containing fascinating archival documentation of E.A.T., for example—can be properly looked at and taken in. Go see it, and then, go again.

“Robert Rauschenberg” will be on view at Tate Modern, London, from December 1, 2016 – April 2, 2017.