Art & Exhibitions

Major Feminist Art Installation ‘The Sister Chapel’ Resurrected After 37 Years

A key work of 1970s feminism rises from the shadows.

A key work of 1970s feminism rises from the shadows.

Sarah Cascone

A major feminist art installation from 1978 is about to be resurrected in New Jersey, where the Rowan University Art Gallery in Glassboro, New Jersey will show The Sister Chapel for the first time in nearly four decades.

In 1974, artist Ilise Greenstein enlisted a group of twelve artists to help bring to life her vision of a hall of fame for women. The work’s title is an obvious reference to Michelangelo‘s fresco on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, but the figures enshrined in The Sister Chapel represent important women from history, religion, and myth, rather than Biblical figures.

The portraits include Italian Renaissance great Artemisia Gentileschi; Betty Friedan, author of The Feminine Mystique; and 15th-century martyr, saint, and soldier Joan of Arc.

Greenstein was inspired to create the ambitious work, both by and for women, while studying the famous Vatican fresco.

The Sister Chapel installation at PS1, Long Island City, New York, January–February 1978. Photo courtesy of a private collection, used with permission.

“Where was woman in man’s relationship to God?” she recalled wondering in a 1983 interview with Dorothy D. Horowitz for the William E. Wiener Oral History Library of the American Jewish Committee. “God and Adam touching hands—almost. Where was Eve?… I decided that I would challenge the Michelangelo concept; I would retell the myth of creation.”

After years of collaboration, The Sister Chapel debuted at PS1 in Queens in 1978, featuring eleven larger-than-life portraits of heroic female role models and an abstract ceiling panel by Greenstein. The original plan called for the chapel to be enclosed in a tent-like nylon and velvet structure by Maureen Connor, but due to cost-constraints the final product only included a model of her design.

Alice Neel, Bella Abzug—The Candidate (1976) from The Sister Chapel.

Photo: © the estate of Alice Neel; Rowan University Art Gallery.

The Sister Chapel was shown again that year at SUNY Stony Brook, and in 1979 at Cayuga County Community College in Central New York, as well as in 1980 at the Associated Artists Gallery in Fayetteville, New York. The final two venues presented an incomplete version of the work, without the ceiling and one of the figures, Sharon Wybrants‘s Self-Portrait as Superwoman (Woman as Culture Hero), 1977–78.

Though originally reviewed in publications such as the New York Times and Newsday, The Sister Chapel has fallen into obscurity in the decades since it was last shown. Over recent years, the work was acquired, piece by piece, by Rowan University at the behest of professor Andrew Hottle, author of the 2014 book The Art of the Sister Chapel.

June Blum, Betty Friedan as the Prophet (1976). Photo by Andrew Hottle ©June Blum; Rowan University Art Gallery, gift of the artist, 2012.

“Many of these artists have been overlooked, in a way probably unfairly,” Hottle told artnet News of The Sister Chapel‘s contributors in a phone conversation. “It’s actually a very important collaboration.”

He cites the 1985 death of Greenstein, who was one of the project’s greatest advocates, as part of the reason it has not maintained a higher profile. A parallel could be Judy Chicago‘s installation The Dinner Party, which has been permanently installed at the Brooklyn Museum‘s Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art since 2007.

Sylvia Sleigh, Lilith (1976). Photo by Karen Mauch Photography, © Friends of Sylvia Sleigh; Rowan University Art Gallery, Sylvia Sleigh Collection.

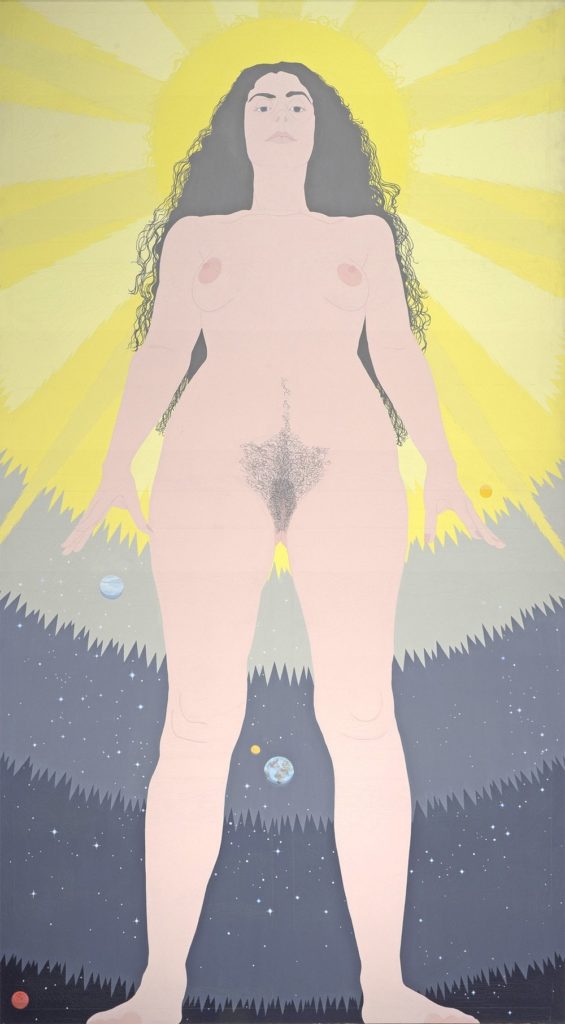

In addition to the works by Greenstein, Wybrants, and Connor, The Sister Chapel includes the following paintings: Bella Abzug—the Candidate (1976) by Alice Neel, Betty Friedan as the Prophet (1976) by June Blum, Marianne Moore (1977) by Betty Holliday, Joan of Arc (1976) by Elsa M. Goldsmith, Artemisia Gentileschi (1976) by May Stevens, Frida Kahlo (1976) by Shirley Gorelick, God (1977) by Cynthia Mailman, Durga (1977) by Diana Kurz, Lilith (1976) by Sylvia Sleigh, and Womanhero (1977) by Martha Edelheit.

When Hottle began researching The Sister Chapel a decade ago, he found a dearth of scholarship on the project. “I thought this was odd given how impressive it was,” he noted. Hottle was pleasantly surprised, however, to learn that almost of all of its individual pieces still belonged to the artists or their families.

Diana Kurz, Durga (1977). Photo by Karen Mauch Photography, ©Diana Kurz; Rowan University Art Gallery, gift of the artist, 2013.

He began inquiring about possible donations, and found that there was a great interest among the artists in bringing the works back together to be seen as originally intended. (Sleigh even went so far as to donate her entire personal collection of 100 works of art by 60 women artists to Rowan.)

Today, almost the entire project belongs to Rowan, the only hold-outs being Stevens and the private collector who now owns Holliday’s canvas. Those two paintings are on loan to the university for the upcoming exhibition, and Connor’s fabric enclosure is being fabricated for the occasion. “In a way, this is the first time it’s really being seen the way they wanted it,” said Hottle.

The Sister Chapel installation at PS1, Long Island City, New York, January–February 1978. Photo courtesy of a private collection, used with permission.

Bringing the full Sister Chapel vision to life is a major achievement, given the collaborative nature of the piece. “Most of the time, one person or a group of persons tends to dominate, but this was very much an equitable arrangement,” Hottle noted. That aspect of it makes it truly in the spirit of the women’s movement, where the goal was to help women achieve and support other women.”

“Many of them did not imagine that this would ever resurface,” Hottle admitted. “It was buried for so long that they thought maybe no one would ever find an interest in it.”

Cynthia Mailman, God (1977). Photo by Karen Mauch Photography, ©Cynthia Mailman; Rowan University Art Gallery, gift of the artist.

Greenstein, had she lived, would not have been as surprised: “I knew that this would be tremendously historically important,” she told Horowitz during the oral history project. “It would be an artwork that would sum up something that was happening in the ’70s.”

The Sister Chapel is on view at the Rowan University Art Gallery West, Westby Hall, 201 Mullica Hill Rd., Glassboro, New Jersey, March 28–June 30, 2016.