Reviews

Black Power Comes to Tate Modern in an Urgent Show Charting a Movement’s Rise

'Soul of a Nation' celebrates works by African American artists, many shown in the UK for the first time.

'Soul of a Nation' celebrates works by African American artists, many shown in the UK for the first time.

Hettie Judah

Tate Modern’s project of exploring less-visited art histories has hitherto favored work by artists that, by dint of either gender or geography, have not received the attention they deserve. That in 2017 this project should extend to a major show of mid-century works by African American artists—almost all little known in the UK—is simultaneously shocking and, alas, not that surprising at all.

There are many parallel narratives running through “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power”—Tate Modern’s outstanding summer exhibition—but conspicuous among them is the fight for presence, visibility, and value.

For one, there’s a pervasive lack of nurture: Phillip Lindsay Mason’s The Deathmakers, (1968), a chilling painting showing Malcolm X’s corpse raising an accusing finger at the skeletal white policemen carrying his body, could not be included in the show because no record could be found of its sale or ownership. A photograph showing Noah Purifoy leaning against his sculpture Totem (c.1966) indicates that it was originally almost double the height of the version on show, suggesting that segments of it were broken or lost over time.

These are just two examples from the roll call of art destroyed, lost, or hidden in storage, unseen for decades. The backstory of how curators Zoe Whitley and Mark Godfrey tracked down the works for “Soul of a Nation” would likely make for some fascinating reading in itself. It would be interesting to know, too, how many works required serious TLC from the conservation department before going on display: as it is, the show pops and sparkles with colour and clean, glossy surfaces.

Emory Douglas, 21 August 1971, ‘We Shall Survive without a doubt’ (1971). Courtesy Center for the Study of Political Graphics (Culver City, USA).

The works are shown in loose clusters of alliance: there are rooms dedicated to Chicago’s AfriCOBRA and New York’s Spiral groups, and artists associated with the Manhattan gallery Just Above Midtown, as well as abstract art, photography, and portraiture. Each suggests different questions concerning the role of the artist engaged with African American identity in this turbulent era in the USA: where should art be shown? What audience should it be for? Could there be such as thing as a “Black Art”? Did artists have a duty to work for and represent their community? What materials should they use? Should they fight for representation in the mainstream or forge an alternative system?

“Soul of a Nation” makes a virtue of its artists’ diverse strategies. Here we find the crisp and provocative graphic works created by Emory Douglas for the back cover of Black Panther Newspaper, and documentation of the (now destroyed) Wall of Respect, a mural painted on a public wall in the South Side of Chicago by OBAC (the Organization of Black American Culture).

Benny Andrews, Did the Bear Sit Under a Tree? (1969). Courtesy the Emanuel Collection, Estate of Benny Andrews/DACS, London/VAGA, NY 2017.

In Chicago too, AfriCOBRA (the African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists) drew up a manifesto for new “Black Art,” creating works throbbing with Kool Aid colors, panels of metallic shine and text integrated into the pattern of the work: “Black Children Keep You Spirits Free,” “Uphold Your Men.” Many were produced as prints or editions; radical art was part of the radical politics, intended to connect forcefully with a mass audience. (In this aspect, the show connects interestingly with Christine Macel’s investigation of 1970s feminist and community art in “Viva Arte Viva” at this year’s Venice Biennale.)

The show’s dynamism comes in part from the intertwining of artistic investigation and agendas of representation and dissent. Photographer Roy DeCarava’s intimate portraits of family life and political protest are, at the same time, technical exercises in beautiful darkness, the light so leached from the image that one struggles to pick out forms faint as breath in the silvery black of his prints. Sam Gilliam’s vast, loose, abstract painting April 4 (1969) was painted in the year following Martin Luther King’s assassination on that date. Its bleeding, washy stains of red and purple hint at regicide; its slack canvas, at a shroud.

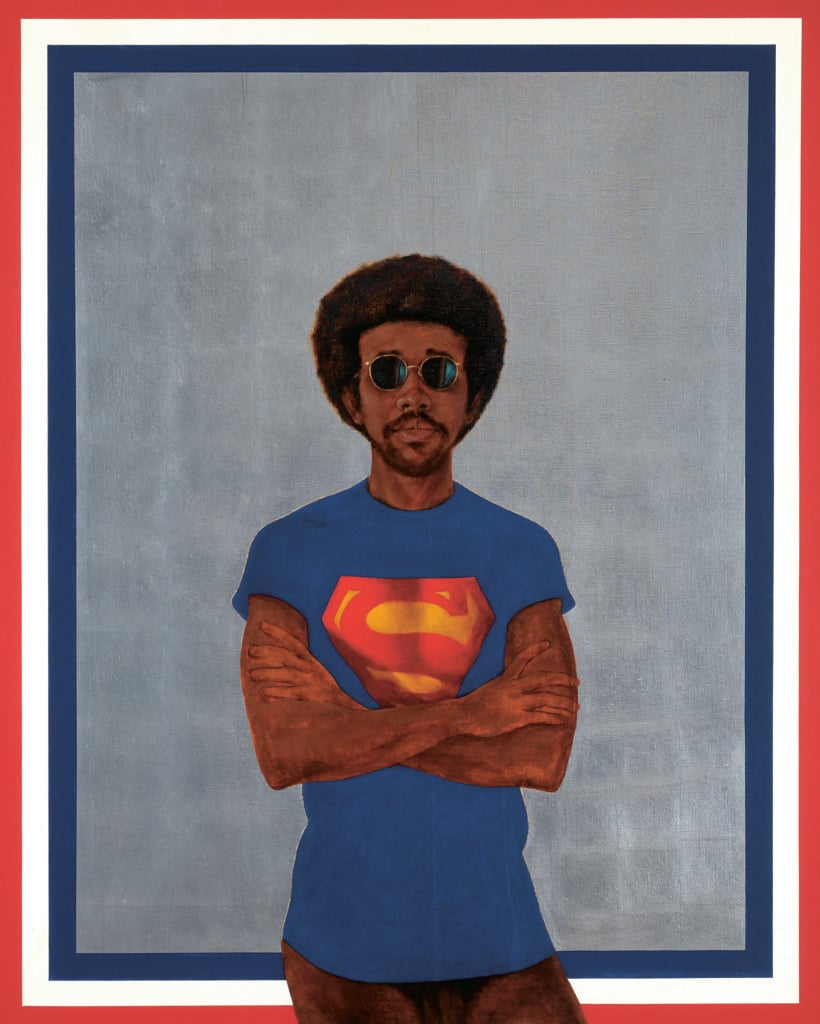

Barkley Hendricks, Icon for My Man Superman (Superman Never Saved Any Black People–Bobby Seale), (1969). Courtesy Barkley L. Hendricks and Jack Shaiman Gallery, NY.

Can we take a moment for Barkley Hendricks? Oh my, hearts will break. He is, both literally and figuratively a massive presence in this show. Two self-portraits flank his seductive tonal study What’s Going On (1974), picturing five figures, four glamorously dressed in white, one nude. The care and precision with which Hendricks captures skin color, texture, and sheen is a political act in itself in the face of cartoonish stereotyping of the Aunt Jemima ilk—a figure who, elsewhere in this show, is fierced up and armed with a gun courtesy of Betye Saar. To its right, Hendricks’s Brilliantly Endowed (Self Portrait) (1977) presents the artist gorgeous and naked save for his hat and tennis socks, short neither on skill nor on ego. To its left, he appears as a self-anointed icon in a superman t-shirt, pubis just on view, against an aluminum leaf background.

David Hammons’s body print Injustice Case (one of a number of major works by the artist in this show) is an audacious tour de force. It shows a grease print of the artist’s body, bound hand and foot and gagged on a chair, in reference to the courtroom restraint of the political activist Bobby Seale. The pigment-dusted print is framed in cut-up portions of the American flag.

Speaking in 1975, Hammons lamented the fact that work by African American artists only seemed to make it into mainstream institutions when it was grouped together: “Throwing everyone into a barrel—that bothers me, that that’s still happening.” “Soul of a Nation” is a great exhibition, but, more than 40 years on, it is yet another group show, carrying the work of artists—Hendricks, Hammons, Gilliam, Saar among them, as well as Norman Lewis, Romare Bearden, Faith Ringgold, and others—well deserving of solo outings. Let’s hope this is but a first step for Tate, rather than the end of the journey.

“Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power” is on view at Tate Modern until October 22, 2017

Following its presentation at Tate Modern, the exhibition will tour to Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas and the Brooklyn Museum, New York.