In a 1923 cartoon, a bearded, middle-aged John Singer Sargent ascends the stairs of London’s National Gallery, greeted by a pantheon of artists including Gainsborough, Rembrandt, Van Dyck, and Velázquez. “Well done,” the artists proclaim in the caption. “You’re the first master to break the rule and get in here alive.”

It is hard to overstate just how popular John Singer Sargent was during his life. But the artist behind portraits of high society fixtures from John D. Rockefeller to Isabelle Stewart Gardner began to abandon the format that made him famous—painting—in 1907, opting instead to focus on murals, a form he thought would boost his reputation as more than just an artist for hire by the rich. To make ends meet, however, he continued to make society portraits, but chose to do them in charcoal, a less time-consuming medium than oil.

Portrait of John Singer Sargent by James E. Purdy in 1903. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

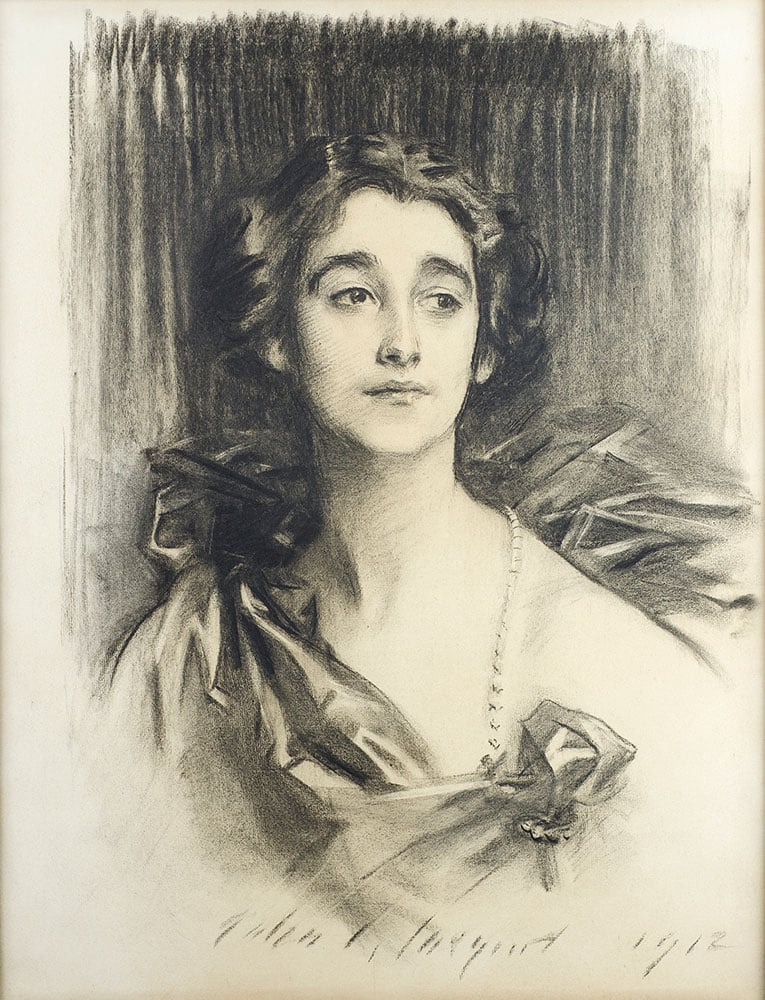

This charcoal portraiture, for which Sargent charged less than a painting but could complete in just three hours each, is the subject of the exhibition “John Singer Sargent: Portraits in Charcoal,” on view until January 12 at the Morgan Library & Museum and subsequently at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in Washington. The show calls the charcoals “often overlooked,” although it is worth noting prior shows, including the 1999 exhibit “John Singer Sargent, Draughtsman,” examined the artist’s work in the medium.

The current Morgan show argues that Sargent reinvented himself at the height of his success as an oil portraitist and demonstrated great skill as a “virtuoso draftsman” in the charcoal portraits. But it remains debatable whether the 750-odd charcoal images, comparatively convenient and slapdash, rise to anything near the prior oils or future murals.

The show also raises a bigger question about how we examine the work of acknowledged masters: Just because one element of their oeuvre is famous, does that mean everything they make is worth examining—and admiring? And, even more fundamentally, how do we tell the difference between a good drawing and a bad one?

The Case for Sargent as Draughtsman

Sargent advocate Laurel Peterson, a curatorial fellow in the Morgan’s drawings and prints department, says the artist’s virtuosity derived from his “ability to give a powerful sense of his sitters, both of their characters and of their liveliness.”

She notes that the artist “approached each drawing with confidence—a confidence that is palpable in the bold strokes of charcoal that we see applied to the page. He also deftly rendered details, paying particularly close attention to the eyes.” He also brings a painterly touch, expertly building dark to light. Unusually, he frequently used the crust of bread as an eraser to scrape away excess charcoal.

Peterson turns to three works in the show to highlight Sargent’s skill as a charcoal portraitist. In his 1913 portrait of Mary Anderson, Sargent outlined the American actress’s scarf with a sharp instrument, “giving the impression of a filmy, gauzy fabric,” she notes.

Sargent’s 1910 portrait of Lady Evelyn Charteris Vesey, meanwhile, reflects the kind of “forceful portraiture” that the artist could make using black on black. “Strengthened outlines give definition to her shoulder, and the rich dark background allows her face to stand out,” Peterson says.

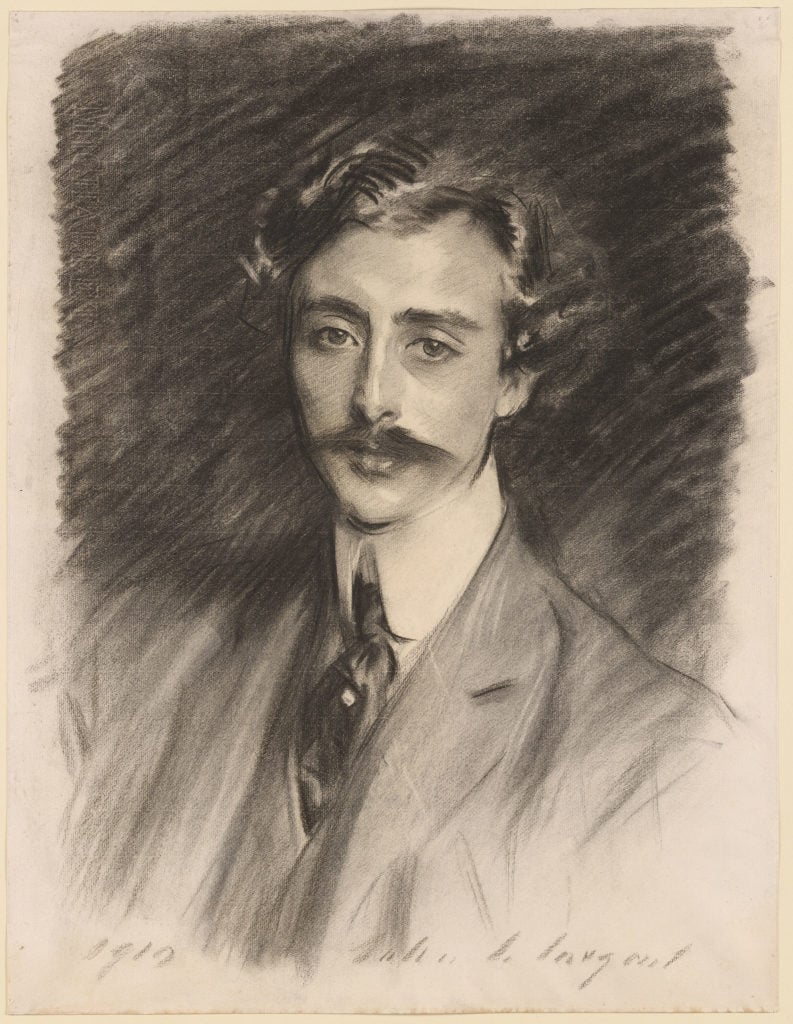

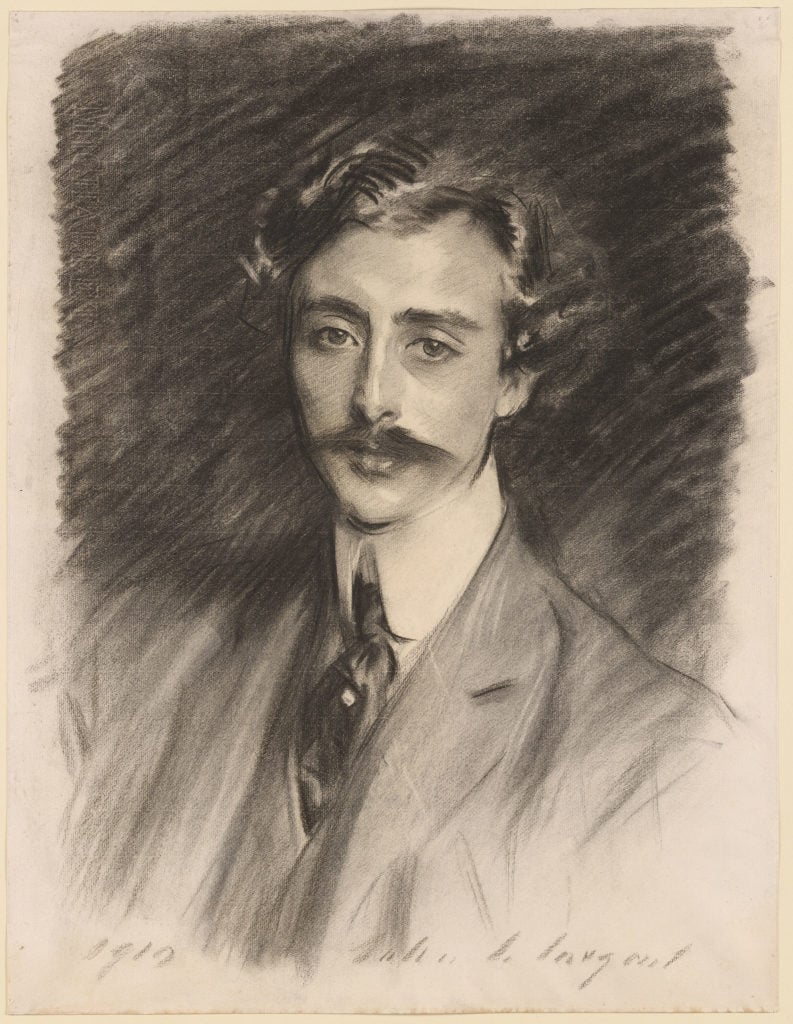

John Singer Sargent, Portrait of Ernest Schelling (1876–1939) (1910). Courtesy of the Morgan Library & Museum.

And in his 1910 charcoal portrait of American musician Ernest Schelling, Sargent demonstrated his “striking” ability to navigate light and shadow by using the crust of bread to remove charcoal and create highlights in lieu of white chalk. “You can see this in Ernest Schelling’s hair, where the highlights add texture and definition,” Peterson says. “They are visible on Schelling’s forehead and nose as well, creating a play of light across his face.”

Peterson maintains the charcoals aren’t compromises, even though they were substantially cheaper than their painted counterparts (about $400, compared to more than $4,000). “The price of the portraits reflected not only the hours of labor but also the cost of materials,” she says.

For all these reasons, Peterson sees the charcoals as “neglected gems” rather than objects that curators and historians were right to overlook. “They’re often hidden from sight, remaining in private collections or kept in museum storage because they are light sensitive,” she says. “Many people who think they ‘know’ Sargent will be astonished by the vivacity of these works in charcoal, which make a profound impression in person.” The artist “didn’t need color to create drama and sparkle,” she adds.

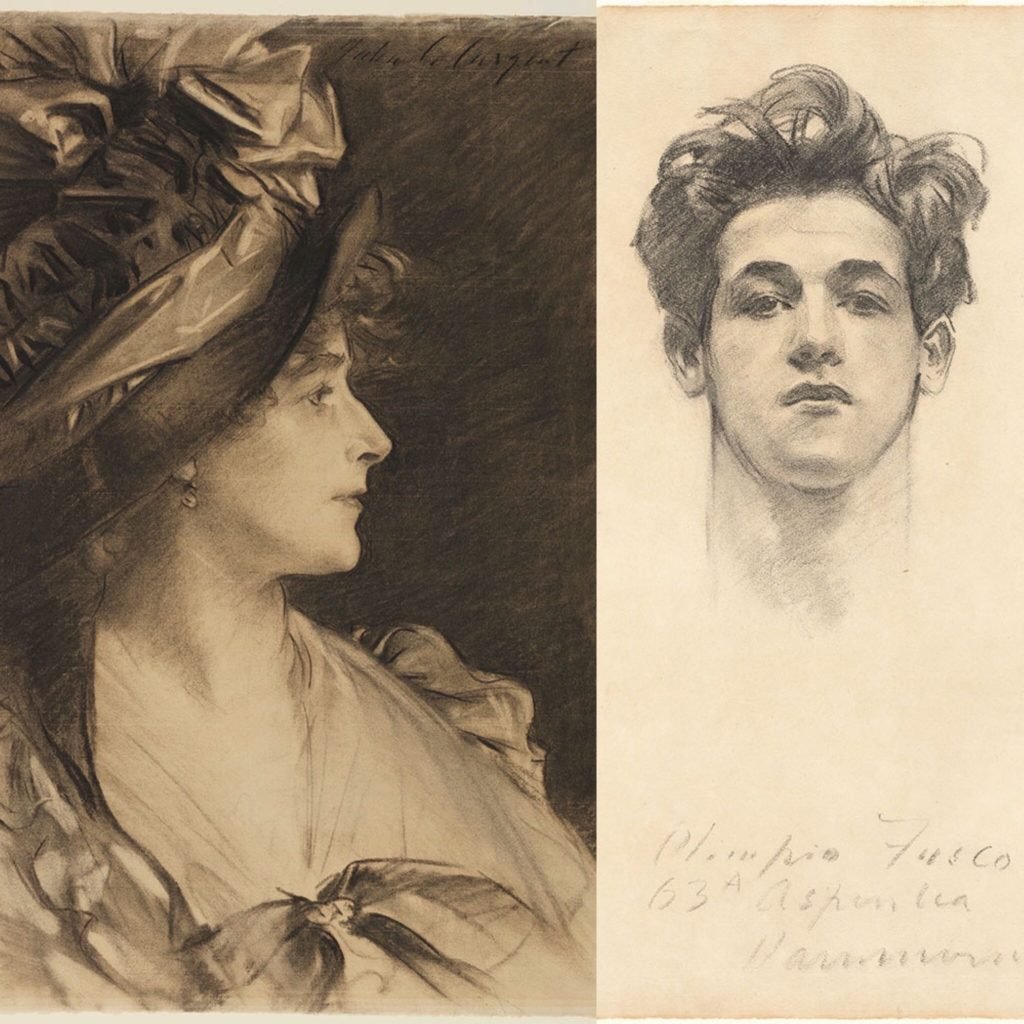

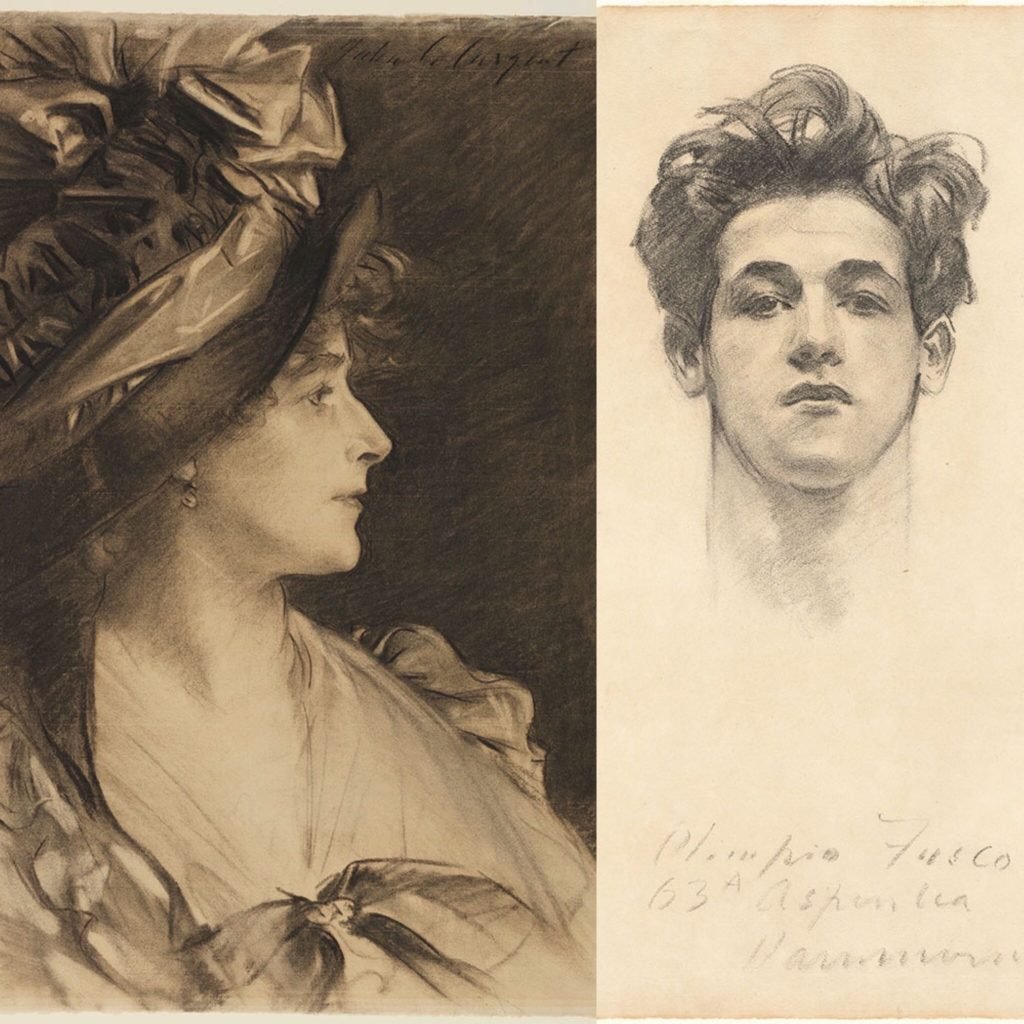

Left, John Singer Sargent, Gertrude Kingston (ca. 1909) and Olimpio Fusco (ca. 1900–1910). Courtesy of the Morgan Library & Museum.

The Case Against

Not everyone agrees with the Morgan’s assessment, however—including the artist himself. Sargent complained that sitters too often meddled in his portraits, which was part of the reason he moved away from the oils in 1907. Yale University’s Sally Promey, author of the 1999 book Painting Religion in Public, noted the “strongly gendered” language that the painter used in dismissing his portraiture. The artist was quoted as saying in 1918, “I lost my nerve for portraits long ago when harassed by mothers, critical wives and sisters.”

The Morgan exhibit shares with viewers a bit of Sargent’s self-doubt and criticism of some of his own charcoals, as well as examples of times sitters or their family and friends felt that the artist hadn’t captured an accurate likeness. The show leaves visitors with less of an impression of the gendered aspect that Promey notes, which is regrettable and fertile ground for future exhibitions. But walking through the Morgan show, one also comes away with questions about Sargent’s virtuosity with the charcoal stick.

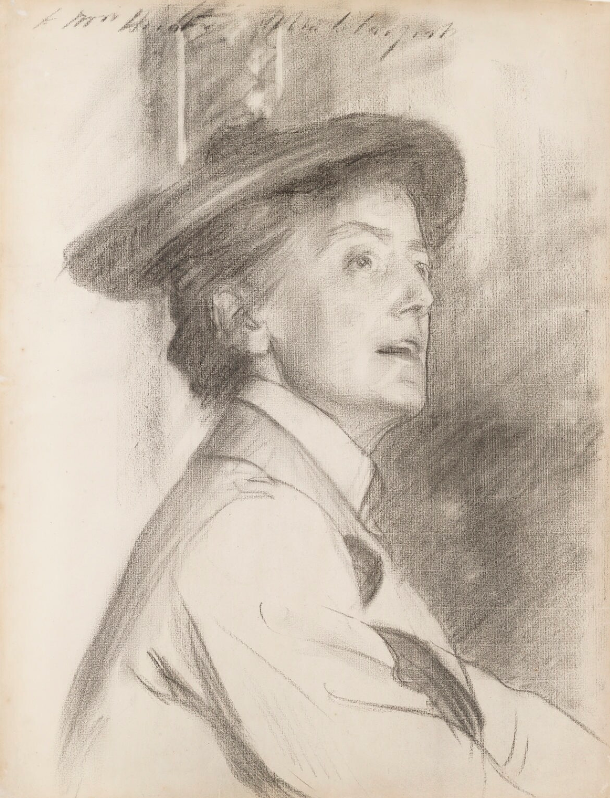

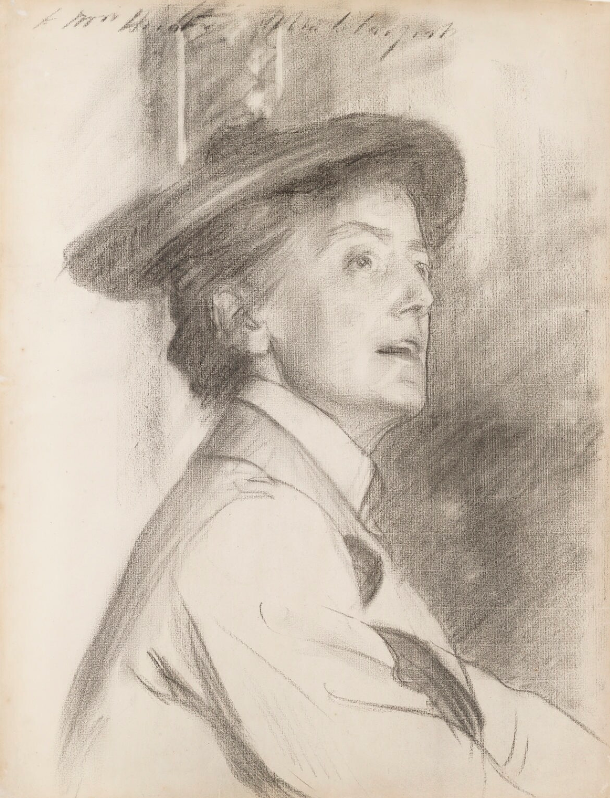

John Singer Sargent, Dame Ethel Mary Smyth (1901). Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Rather than masterfully painting with charcoal, Sargent often flattens faces with unfortunate and unnecessary black outlines. That’s just what he does in a circa 1900 portrait of Jeanette Jerome Churchill on the right side of the heiress’ face, and in a 1901 portrait of Ethel Smyth on the left side of the composer’s face. In both, Sargent looks less like a master in the company of Rembrandt and Van Dyck and more like someone reaching in vain to try to understand a form.

In a 1914 portrait of Ruth Draper, “energetic lines of charcoal in the actress’s hair demonstrate Sargent’s confidence and speed as he produced the portrait,” a wall label states. But the work shows anything but. Many of these charcoals look like they could be whipped off in 10 or 15 minutes, but we know that Sargent spent two or three hours on each. The kind of confidence the artist brought to his oil portraits, which are themselves often prettier than they are sophisticated, often seems conspicuously absent from the charcoals.

Maybe instead of neglected gems about which the artist was his own worst critic, the charcoals might really be a lot less than what Sargent was capable of—which is to say, maybe we should take his criticism of many of them at its word.

“John Singer Sargent: Portraits in Charcoal” is on view at the Morgan Library & Museum,225 Madison Avenue, New York, October 4, 2019–January 12, 2020.