Art & Exhibitions

Yes, Black Women Made Abstract Art Too, as a Resounding New Show Makes Clear

The show is a logical complement to the recent "We Wanted a Revolution."

The show is a logical complement to the recent "We Wanted a Revolution."

Ben Davis

Earlier this year, “We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85” at the Brooklyn Museum dropped like a bomb. Mining a seam of engaged, truth-telling art by black women from the Civil Rights era onward, “We Wanted a Revolution” both recovered an overlooked past and served as a resource for a present smoldering with renewed struggles over racial justice. It will have a long afterlife. I hope part of that afterlife is interest in “Magnetic Fields: Expanding American Abstraction, 1960s to Today,” freshly opened at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC.

To me, “Magnetic Fields” feels like a Chapter 2 to “We Wanted a Revolution”—even if it is also defined by a contrast. Because “Magnetic Fields” focuses on artists who were black, female, and committed their passions specifically to abstract art.

Understanding the mental space defined by these two shows—between ideas of art as a weapon in struggle, and art as a vehicle to transcend a world of struggle, and all the many gradations in between—is another piece of the puzzle of making sense of this past for the present.

Installation view of “Magnetic Fields” with [left to right] works by Jennie C. Jones, Shinique Smith, and Howardena Pindell. Image: Ben Davis.

Hassinger, for her part, is outspoken about the necessity of resisting the temptation to reduce black art to black political art: “Insisting that black people talk about their blackness and about their trauma almost exclusively makes it a style, a trend like Minimalism,” she says in the catalogue. “The sale of black trauma is artificial, offensive, and being an artist is not about being artificial.”

Maren Hassinger, Wrenching News (2008). Image: Ben Davis.

Her work in the show, Wrenching News (2008), is even in some way about that thought: She takes newspapers that testify to the daily horrors of life in the US, and transforms them into a wild, abstract garden.

Curators Erin Dziedzic and Melissa Messina write that assembling the material in the show “required a reexamination of numerous little-known exhibition records, catalogues, and ephemera.” Perhaps these scholarly barriers account for what is weakest about “Magnetic Fields,” that it is not always so clear why this or that work, from this or that period of a career, was picked. For me, new to a lot of these figures, I just can’t always say whether a particular piece makes the strongest case for a practice, or was just what is available.

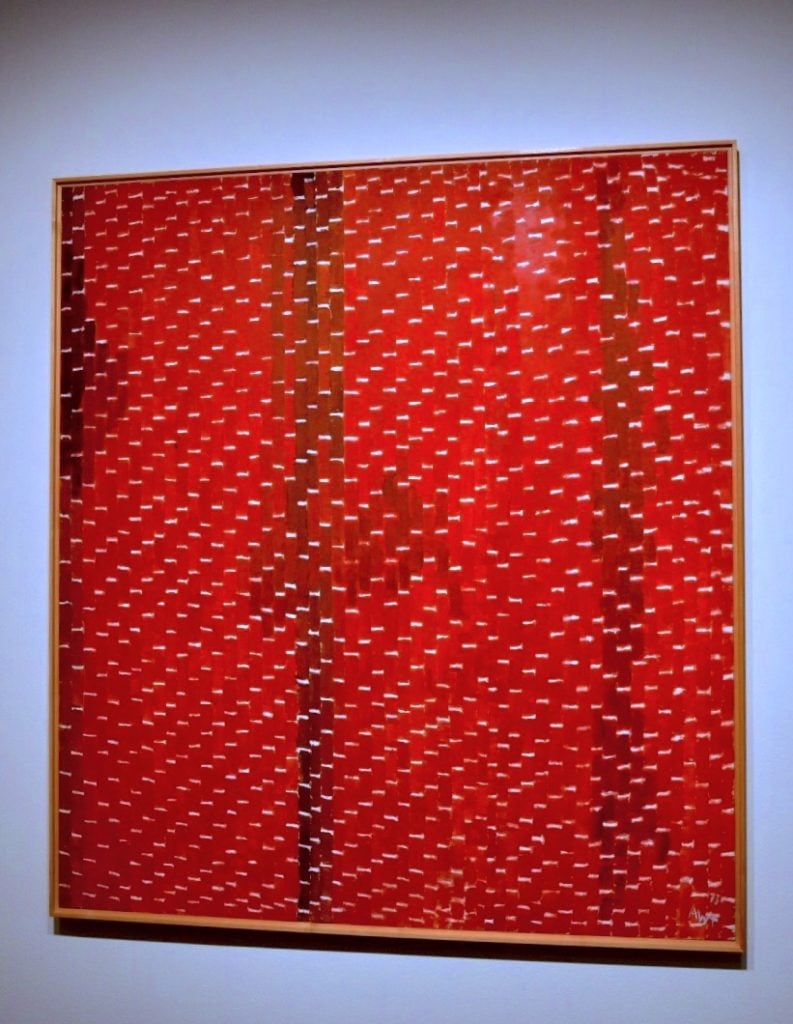

Alma Thomas, Orion (1973). Image: Ben Davis.

Probably the most famous figure in “Magnetic Fields” is DC’s own Alma Thomas (1891–1978), the elder stateswoman here, represented by the tremulous but architecturally solid red lattice of Orion (1973), from the National Museum of Women in the Arts’s collection.

Thomas was a beloved figure, never quite in line with her Washington Color School contemporaries, and not a real success until after retirement. Still, her graceful abstractions, often with cosmic themes, would make her the first black female artist to have a solo show at the Whitney, in 1972—though this overdue inclusion itself was a reaction to the militant black art activism of the era, with the Black Emergency Cultural Council putting pressure on that institution in the late ’60s and early ’70s.

Despite Thomas’s notoriety, there is no doubt that she has been neglected by the canon. The Museum of Modern Art bought its first Thomas only in 2015. And she’s the famous one here!

The relationship between black abstraction and black activism was not always easy, and mostly it was not so synergistic. White audiences expected work that testified to the experiences of racism, which meant figuration of some kind. And as Lowery Stokes Sims notes, a certain tradition of black activism also considered abstract art too ingratiating to mainstream Euro-American tastes, too mute on the pressing realities of racism.

Betty Blayton, Consume #2 (1969). Image: Ben Davis.

Of course, a yen for abstraction didn’t mean that these artists were utterly disengaged from the world. Betty Blayton (1937–2016) casts a long shadow as an advocate, helping to found the Studio Museum in Harlem, the Harlem Children’s Carnival, and more. Her own art has been until recently under-known. Here, a serene tondo striped with diaphanous drips of ocher, blue, and lavender shows what a loss that is.

In any case, the upshot is that the artists of “Magnetic Fields” were often internal exiles within their own art worlds; they worked “on the periphery of a periphery of a periphery,” as the curators put it.

Brenna Youngblood, YARDGUARD (2015). Image: Ben Davis.

“Magnetic Fields” contains some audacious, more-recent stars to connect its legacy to the present (Abigail DeVille, Shinique Smith, Kianja Strobert, Brenna Youngblood). For me, however, the show’s most satisfying achievement is the duty it does in bringing representatives of several older generations of exiles in from the cold.

I’m thinking of meticulous interlocking fields of powdery colors from Nanette Carter (b. 1954), or the small, colorful, wonderfully expressive triangular relief constructions by Lilian Thomas Burwell (b. 1927).

Lilian Thomas Burwell, Menageri (2006). Image: Ben Davis.

My key discovery in “Magnetic Fields,” however, may be Mary Lovelace O’Neal (b. 1942), a very accomplished painter who was once chair of the University of California, Berkeley art practice department. According to the catalogue, Amiri Baraka, leader of the Black Arts Movement, once told O’Neal that her all-black abstractions in the 1970s were not Black enough. “How much blacker can it get?” she is supposed to have replied.

O’Neal’s big statement in “Magnetic Fields” is the wall-spanning, startlingly titled Racism Is Like Rain, Either It’s Raining or It’s Gathering Somewhere (1993). The canvas is grounded in lampblack, a pigment that she has taken up for its dense materiality and symbolic potency. One half is a nearly empty field of this matte darkness, subtly agitated but solid; the other is a dripping cloudfront of exuberant pinks, blood reds, whirling blues, and consuming, darker blacks.

Mary Lovelace O’Neal, Racism Is Like Rain, Either It’s Raining or It’s Gathering Somewhere (1993). Image: Ben Davis.

The title gives the drama of the painting a content. O’Neal has said that her art “spoke, in perhaps a very abstract way, of my struggles as an African American, as an African American woman.” But that “very abstract way” is also clearly important to her, the specific, wordless dynamics of paint on canvas.

The tension between the two halves of this painting, the empty space and the busy color, redoubles the external contrast between the biographical narrative that you can project into the composition and the independence of its abstract forms. That tension forms part of the content of the work.

And that, finally, brings us to Jennie C. Jones (b. 1968), a kind of outlier even within this group of outliers. “Even in a group of black artists, I wasn’t part of the main discourse,” she tells the art critic Lilly Wei in the catalogue. “I was the one doing the weird conceptual thing.”

In the show, that thing looks like a series of paintings—sleek, stylish riffs on Ellsworth Kelly’s hard-edged abstraction, all blacks and whites and grays. They have musical titles such as Muted Measure, Muted Tone Burst With Grace Note, and Tritone (Dissonant). Jones often works with music and musical metaphors, and you can almost read them as scores, rhythmic melodies of light and shade.

Works by Jennie C. Jones in “Magnetic Fields.” Image: Ben Davis.

But the fields of gray are actually found objects: the banal acoustic paneling you find in concert halls.

“There is a tell-your-story expectation and pattern for all artists of color—hence the inescapable narrative,” Jones has said. You can say that these sly conceptual non-narrative paintings are all about mutedness, about courting a knowingly impersonal look that refuses the imperative to testify. But that might also be too easily.

After all, acoustic paneling is all about clearing up noise so that you can hear what is in front of you more clearly. That may be an encoded message of Jones’s work, and may be a way to think of “Magnetic Fields” in general as an intervention: We need to clear up the noise of art-historical stereotypes so that we can perceive the actual voices of these figures—their actual, individual passions and concerns—more clearly.

“Magnetic Fields: Expanding American Abstraction, 1960s to Today” is on view at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC, through January 21, 2018.