Galleries

Galerie Lelong Will Represent the Estate of Mildred Thompson, a Long-Overlooked Figure in the History of American Modernism

Thompson previously had no gallery representation.

Thompson previously had no gallery representation.

Eileen Kinsella

In a 1977 essay, the artist Mildred Thompson wrote that a female dealer once told her “it would be impossible for me to have a show in New York as an artist.” Another gallerist said “that it would be better if I had a white friend to take my work around, someone to pass as Mildred Thompson.”

Forty years later, the artist, who died in 2003, has formal gallery representation for the first time. Galerie Lelong & Co. of New York has announced worldwide representation of her estate. In recent years, the abstract painter has gained growing recognition from museums, but remains little known to much of the art world.

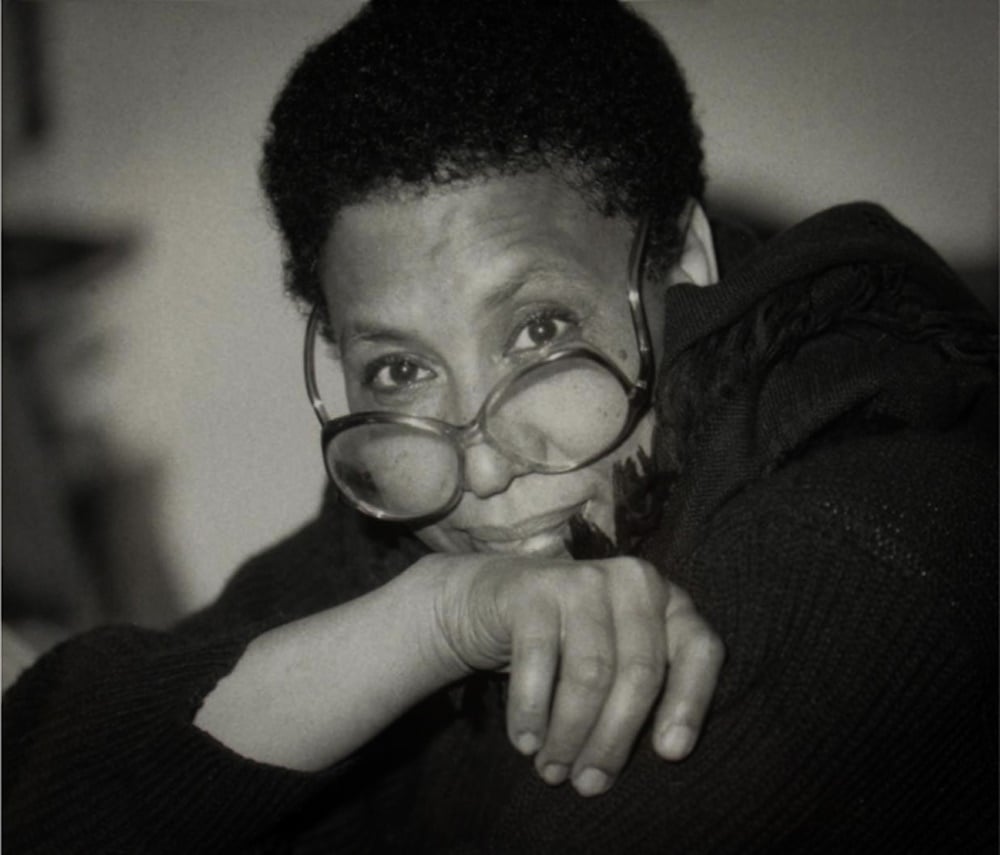

Portrait of the artist, Atlanta, Georgia, 1988© The Mildred Thompson Estate

Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co., New York

A solo show of her work is scheduled to open at Galerie Lelong in New York early next year (“Mildred Thompson: Radiation Explorations and Magnetic Fields,” February 22–March 31). The gallery will also dedicate a booth to her paintings and works on paper at the upcoming Art Dealers Association of America’s annual Art Show at the Park Avenue Armory, which opens in February.

Galerie Lelong’s managing director Mary Sabbatino first encountered Thompson’s work in 2016, when the director of the New Orleans Museum of Art showed her images of several works the museum had just acquired by an older African American female artist. “It’s really beautiful work, it just stuck in my mind,” Sabbatino recalls.

Thompson’s work is also included in the traveling exhibition “Magnetic Fields: Expanding American Abstraction, 1960s to Today,” curated by Thompson estate curator Melissa Messina, and is now on view at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC. Last year, she had a solo exhibition at the SCAD Museum of Art in Savannah, Georgia.

“I thought it had a lot of potential for both recognition and importance in the dialogue of what is abstraction,” Sabbatino says of Thompson’s work. “How artists use the language, and what stories have been left out of the 20th-century canon of Modernism.”

Sabbatino eventually visited the artist’s heir in Atlanta. Because Thompson has not had gallery representation in the past, lots of paintings, pastels, prints, and drawings remain in the estate, but they have not been catalogued—a significant undertaking.

Mildred Thompson, Music of the Spheres: Mercury (1996)

© The Mildred Thompson Estate

Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co., New York

Asked about how the gallery will determine the price of her work given the artist’s lack of primary market activity and auction history (the only two works offered at auction went unsold, according to the artnet Price Database), Sabbatino says she looked to insurance valuations used for museum shows. The modest number of sales during Thompson’s lifetime were also used as a starting point. (MoMA, for example, acquired two of her prints in the ’60s.)

Born in Jacksonville, Florida in 1936, Thompson spent the majority of her career in Germany and France; she went into self-imposed exile after facing racism and sexism in the US. After teaching and exhibiting widely in Europe, she spent the final 15 years of her life in Atlanta, where she was associate editor for Art Papers magazine.

Refined over a four-decade career, Thompson’s signature style of swooping, colorful linear forms was inspired by music and science. Lelong’s addition of the artist to its roster comes as the market has re-evaluated work by women and artists of color from the ’60s and ’70s. But so far, that re-evaluation has been slower to embrace black women.

“I’m really glad that women artists are getting increased recognition,” Sabbatino says. “My hope is that women of color will also share that space and be looked at equally.”

Mildred Thompson<

Magnetic Fields (1991) ©The Mildred Thompson Estate

Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co., New York

“l think her work has a great deal to say to us today, in the sense of the tenacity with which she went about making it, even though she didn’t have recognition in her lifetime,” Sabbatino continues. “She kept making work with great joy.”