Art & Exhibitions

Zehra Doğan Was Jailed for Her Political Art. After a Traumatic Sentence, the Kurdish Artist Has a New Show—With Work Smuggled From Prison

The show features works the artist smuggled out of jail.

The show features works the artist smuggled out of jail.

Matt Hanson

By the length of her thick black hair, the artist and writer Zehra Doğan exudes pride as a Kurdish woman. She wears an elegant nose ring and henna under her lower lip, and speaks of her life and art in Turkish, the language of her oppressors. Her first solo show in Turkey, which recently opened, follows her release from three Turkish jails.

“I proved myself as an artist to the whole world, except for my country,” says Doğan, speaking from London on a video call. The exhibition’s title follows that thinking. “Not Approved” opened on October 9 at a small art space in Istanbul’s Pera district called Kiraathane24, a rare bastion for arts activism in Turkey, including for LGBTQ+ and refugee artists.

The show includes clothing and materials she snuck out of prisons in Mardin, Tarsus, and Diyarbakir, where she was jailed at different times between 2016 to 2019; the latter city of Diyarbakir is her hometown, a place Kurds know as the capital of Kurdistan. Throughout the exhibition’s four rooms, there is scrawled-over newsprint, found material, pieces of writing, as well as paintings, all which champion Kurdish feminism.

Yet her political status still overshadows her creative work. “When you Google the name Zehra Doğan, you always see the news that Zehra Doğan was arrested because of artworks,” says Seval Dakman, who co-curated the show with M. Wenda Koyuncu, both of whom identify as Kurdish. “But we don’t know the artworks of Zehra Doğan.”

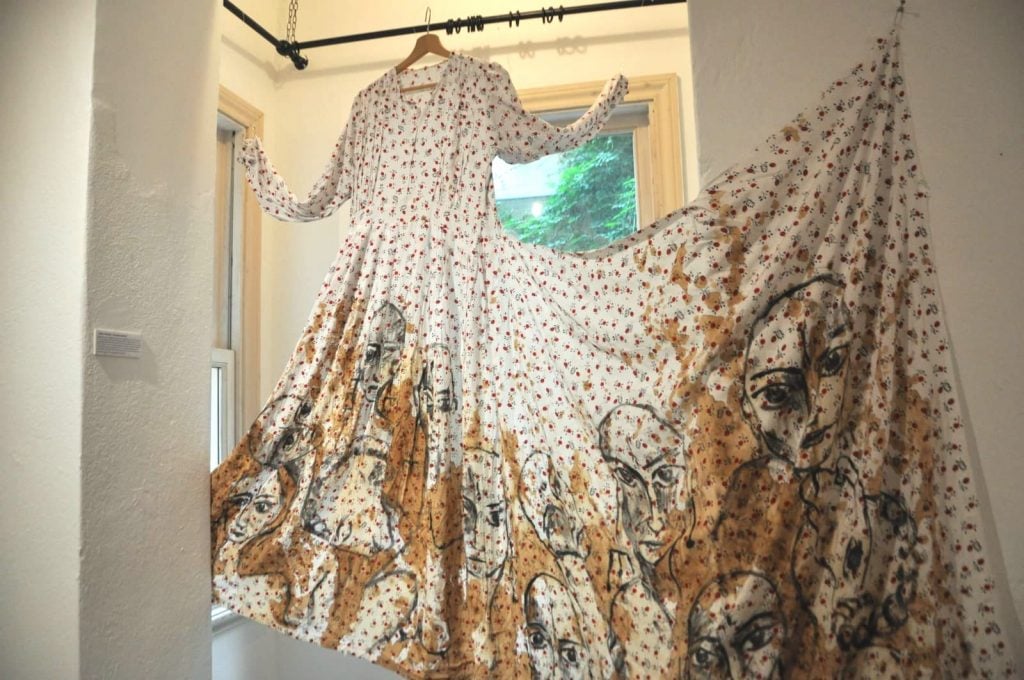

Installation view. Courtesy Zehra Doğan.

Doğan exemplifies the struggle of Kurdish youth who are caught between armed statelessness and cultural survival in the midst of Turkey’s increasingly violent conflict with Kurds, a battle that has been ongoing for decades, but which became more heated since 2015. The Kurdistan Workers Party has been dubbed by the Turkish government as a terrorist organization and many politically active Kurds have been imprisoned.

In 2017, Doğan was jailed for three years after being arrested the year before on terrorism charges for her news reporting, as well as for sharing on social media an image of a painting she made of a Kurdish village destroyed by the Turkish military.

It was while in prison, at age 25, that she finally learned to write in Kurdish, and much of the show in Istanbul features her handwriting in the language, whether on cloth or within the pages of a notebook. She writes about the harsh reality of bodily confinement and political silencing as a Kurdish woman.

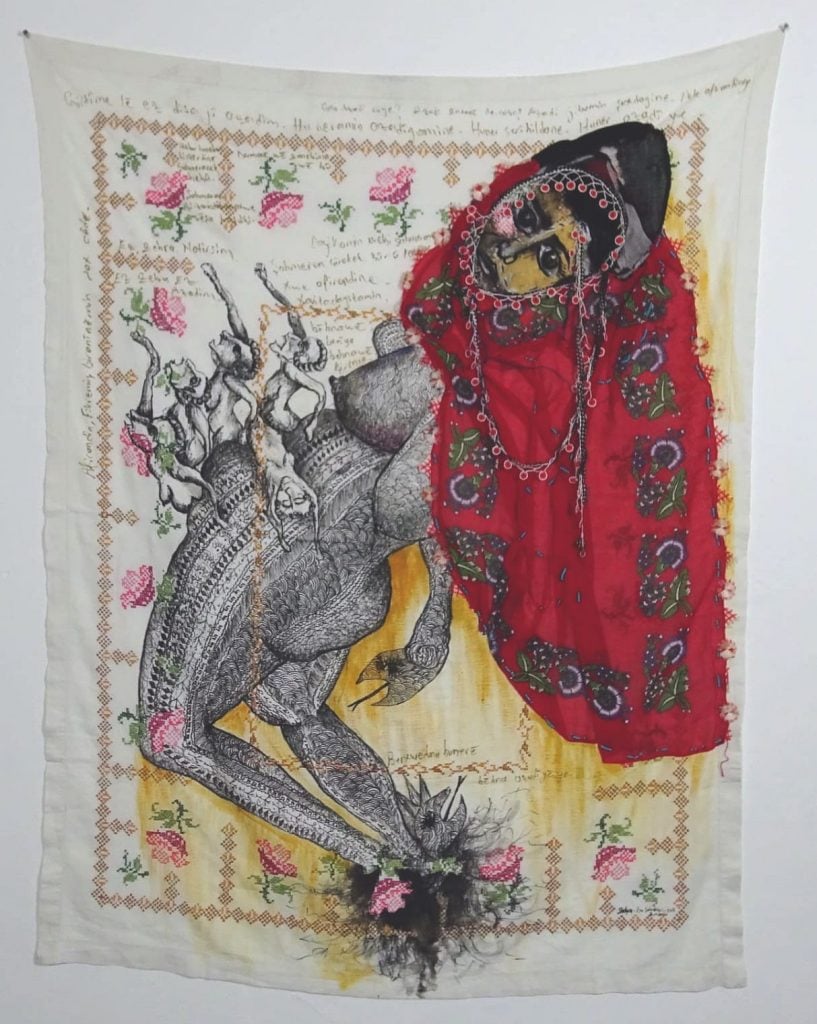

Courtesy Zehra Doğan.

“I cannot say that my activism in my artwork is only about feminism or only about Kurdish political issues, or about human rights. I’m Kurdish. I’m also a feminist. These two things can not be separated from each other. This is my life,” says Doğan. “I always fight against patriarchy, and at the same time I have fought against them as a Kurdish woman.”

Her sentencing brought her international acclaim, particularly in the art world. Her work was on view at the most recent Berlin Biennial. In 2018, she was featured in a major public piece by the street artist Banksy expressing concern over her imprisonment. Others, including artist Ai Weiwei and the Memory Museum in Rojava, Kurdistan, have collaborated with Doğan.

Yet in Turkey, little is known of her work beyond the painting that led to her jailing. “My country hasn’t accepted me,” says the artist. “None of the galleries in Turkey invited me to exhibit, except for Kiraathane24. I wanted to prove myself as an artist in my country.”

Zehra Doğan’s Womanhood. Courtesy Zehra Doğan.

The show does not spare the hardships of Doğan’s jail time. There are sketches of tortured faces in ruddy, blacked paint on newspaper; elsewhere, a public phone is installed with calling cards and a note reading “the world’s shortest 10 minutes,” a nod to the Kurdish diaspora’s struggle to keep connected with one another through persecution. Beside the phone work, a piece titled Womanhood features a simple white dress, browned and sketched with big-eyed faces, outlined black and adorned with Kurdish-style earrings. She snuck it out of jail as dirty laundry.

“This comes from impossibilities,” says Dakman, who is also the owner of Carre D’Artistes Istanbul, a pro-democracy art gallery chain based in France. “She didn’t have the material for art in prison. She demanded it, but they called her work propaganda.” As a result, Doğan used what she could source: menstrual blood, hair, and clothes. “If you are always under oppression, you are always finding solutions,” the curator adds.

Zehra Doğan’s Pain of Shahmeran. Courtesy Zehra Doğan.

One piece in “Not Approved” recalls Kurdish mythology. The story of Shahmeran, a half woman and half snake, is sketched over Doğan’s Kurdish handwriting from her imprisonment in the touristic city of Mardin in a piece called Pain of Shahmeran. Doğan depicts the mythical figure as a contorted woman giving multiple births, her sad face recalling antique mosaic portraiture in Turkey’s southeast. Shahmeran is bound hand and feet by hair, donning the characteristic red shawl traditionally worn by Kurdish women. The figure recurs across several works in the show, sometimes obscured by hair and blood, elsewhere unashamedly menstruating.

“With my artworks I try to fight with my society—not only the Turkish government,” Doğan says. “I am fighting with patriarchy in Kurdish society. We have to fight with them as women.”

Since being released in 2019, Doğan remains subject to threats as an artist, a woman, and a Kurd. Despite her love for her homeland, Doğan says she is unable to return because of security concerns.

But that has not curbed her ability to reach out to young Kurds to encourage them to prioritize cultural activism in the midst of Kurdistan’s armed struggles. In November, she plans to perform at a conference on human rights at Geneva University with Ai Weiwei. Her time in jail will continue to haunt and inform her powerful art practice and her activism, she says: “I didn’t leave my way of being in prison. I am always adding something new and different to my life and art.”