In 1935, Clara Porset settled in Mexico City in political exile from her native Cuba. Well-traveled, and especially well-connected, the designer and educator was a student of international Modernism, having trained in Cuba, New York, and Paris before studying with Bauhaus émigrés Josef and Anni Albers at North Carolina’s famed Black Mountain College.

Landing in Mexico, Porset was already recognized as a force with distinctively progressive views. She used her practice to advocate for affordable and egalitarian-minded design, and strategically deployed local techniques in her furniture and interiors, as well as materials (like leather and jute) optimized to thrive in local climates. Her Butaque chairs are perhaps her best known pieces—adapted from a popular Colonial-era design fusing pre-Columbian duhos and Spanish X-frame forms.

Porset would soon set up her own studio in her adopted city, and in 1952 she mounted a landmark exhibition, “Art in Daily Life,” which radically dissolved established hierarchies of art and craft by featuring industrial-produced furniture and fitted kitchens alongside handmade traditional woven baskets and textiles.

Clara Porset, Butaque Chair (about 1955–56). Collection of Gálvez Guzzy Family/Casa Gálvez. © The Art Institute of Chicago. Photography by Rodrigo Chapa.

Porset serves as the nucleus of “In a Cloud, in a Wall, in a Chair: Six Modernists in Mexico at Midcentury,” now on view at the Art Institute of Chicago. Its impetus came over two years ago, when curator Zoë Ryan was on a trip to Mexico City. After visiting Porset’s archives, Ryan was struck not just by “how much of an advocate she was for a culture of design in Mexico at this period,” but also by her wide network. “That’s how the story began.”

“In a Cloud, in a Wall, in a Chair” brings together a group of artists and designers for the first time: Porset, Anni Albers, Lola Álvarez Bravo, Ruth Asawa, Sheila Hicks, and Cynthia Sargent. All six members of this international, cross-generational group either lived or worked in post-revolutionary Mexico between the 1940s and the 1970s; all of them furthered their practices there; and all of them upended the paradigm of interdisciplinary methodology. According to Ryan, the show is very much the “beginning of a conversation. It’s a very specific moment in these practicioners’s careers. It’s that moment when you see artists grappling with these techniques and ways of making art.”

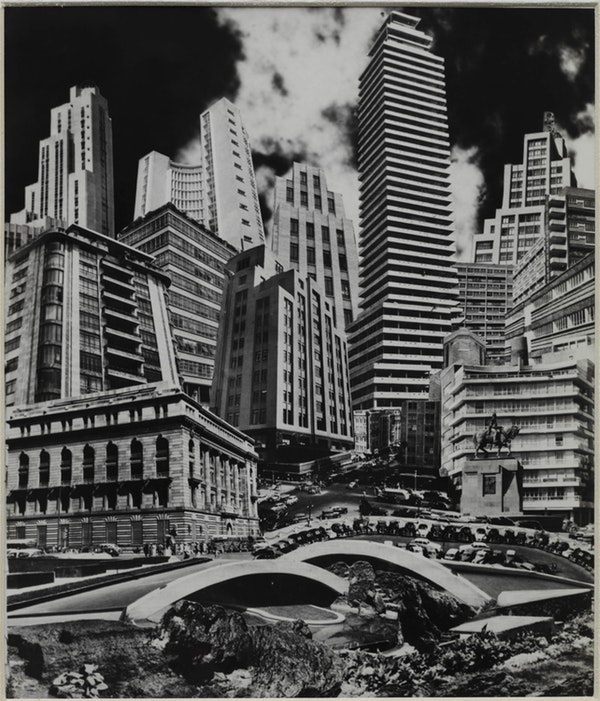

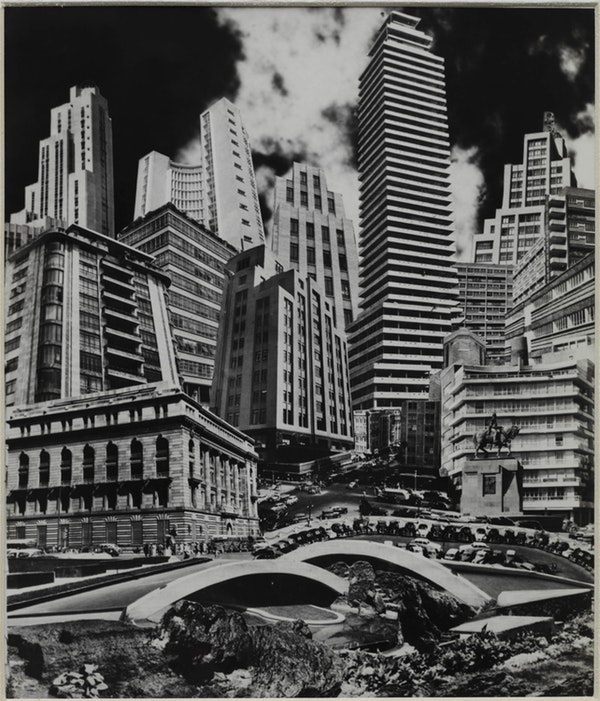

Lola Álvarez Bravo, Anarquía arquitectónica en la ciudad de México (about 1954). Collection of González Rendón Family. © Center for Creative Photography. Photography by Rodrigo Chapa, courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Ryan introduces the exhibition with a ten-foot by twenty-foot photomontage by Álvarez Bravo, depicting a mural she made for an interior of a car factory Porset designed; it signals a country in the midst of mass industrialization. Álvarez Bravo was one of the few women photographers working in the country during this period. Raised in Mexico City, she was a prolific portraitist and photojournalist, and spent much of the 1940s and ‘50s traveling the country photographing its changing rural and industrial landscape. Additionally, Álvarez Bravo was a chronicler of Porset and her work; many of those images appear in the exhibition, along with her photomontages of a changing Mexico.

Overall, the exhibition zeroes in on the exchange of ideas and Mexico as the site of it all. Each practitioner has her own dedicated space in the show, complete with studies, finished works, and associated ephemera. Porset was a connecting thread between the group. After Cynthia Sargent moved to Mexico City from New York and established a weaving workshop turning out popular rugs imbued with her own sense of color and geometry, Porset included her in the “Art in Daily Life” show. Sargent would go on to found the Bazaar Sábado, a popular arts-and-crafts market that continues today.

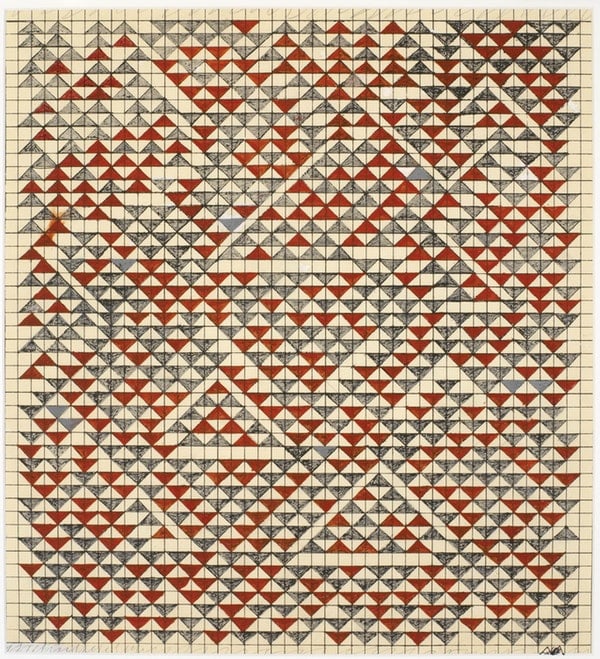

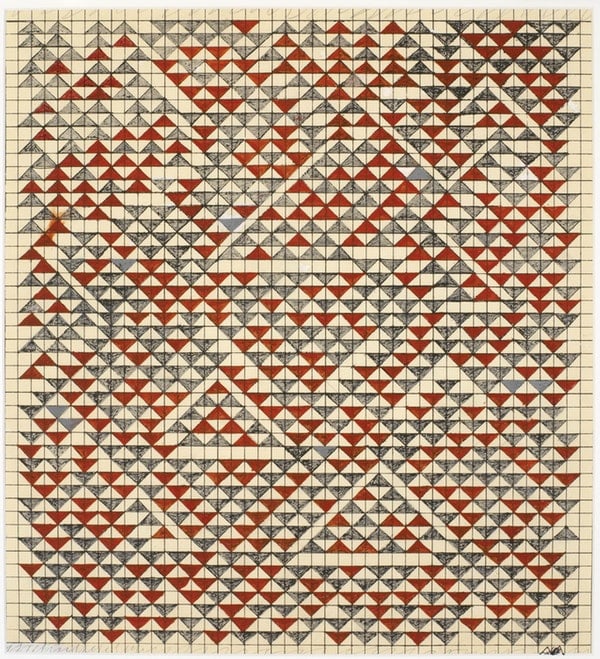

After their time at Black Mountain College, Porset encouraged Anni and Josef Albers to visit Mexico; they subsequently made more than 13 trips. Anni connected with the abstract visual geometric language found in traditional weavings and archeological sites, including the triangular motif that would be incorporated into much of her work.

Sheila Hicks, Learning to Weave in Taxco, Mexico (about 1960). The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Martha Bennett King in memory of her brother, Dr. Wendell Clark Bennett. © Sheila Hicks. Photography: © The Art Institute of Chicago.

“She thought there was so much to learn from here, especially in the modernist vernacular, or ‘universal language,’” Ryan says of Albers. “Crafts were valued, working by hand was something seen as very legitimate, which was not necessarily what they’d come from, what their training had been.”

An especially big discovery, related to Albers’s work at the time, was a weaving she produced for the modernist Camino Real Hotel, which opened in 1968 in Mexico City’s Polanco neighborhood. Commissioned by the hotel’s architect, Ricardo Legorreta, it was thought to be lost. Found in the basement of the hotel, Ryan was surprised to learn the weaving was an industrial-made appliqué. Several of Albers’s Camino Real screenprints are also included in the exhibition.

After visiting Toluca and seeing artisans fabricate baskets by hand with a looped wire technique, Ruth Asawa (another Black Mountain College and Porset alumna) applied it to her drawing practice, bringing it into three dimensions, articulating the sculptural language that would define her body of work. A grouping of Asawa’s delicate, hanging wire sculptures, as well as an egg basket Asawa produced as a gift for Anni Albers, are included here.

Anni Albers. Study for Camino Real (1967). © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 2019. Photography by Tim Nighswander/Imaging4Art.

Though Sheila Hicks is the only artist without a personal connection to Porset, the architect Luis Barragán, Hicks’s major mentor, was a client and friend of Porset’s. Hicks had traveled to Chile and throughout the region, familiarizing herself with pre-Columbian textiles and learning ancient Andean weaving techniques before continuing her studies in Mexico and settling up a workshop in Taxco el Viejo. Ryan has included an array of Hicks’s wall hangings from this period, as well as Falda (1960), a staggering multicolored tangle of wool in which Hicks freed her work from the loom.

“If you’d understood work from the Bauhaus and a much more interdisciplinary approach to practice, you definitely would have gravitated to Mexico where it was playing out in reality,” Ryan says. “Sheila Hicks talks a lot about the fact that she wanted to work and weave but she wasn’t necessarily encouraged. She wanted to remove herself from her environment in America and travel elsewhere to find inspiration. She never looked back.”