In the Studio

In the Studio With Nir Hod

See a 360-degree video of the Israeli, New York-based artist Nir Hod at work as part of artnet's "In the Studio" series.

See a 360-degree video of the Israeli, New York-based artist Nir Hod at work as part of artnet's "In the Studio" series.

Artnet News

To an outside observer, the creation of a work of art can seem like a magical process, with the artist dreaming up a concept and then transmuting it from pure ether into an inspired tangible object. But while the artwork can seem effortless when seen in its finished form, it is in fact the product of trial and error, honed skills, experience, and, in many cases, significant physical exertion—all taking place in the private laboratory that is the artist’s studio. Now, artnet News has teamed up with Dobel Tequila to present the “In the Studio” series, providing a rare glimpse inside this mysterious process with the help of 360-degree video technology. We chose artists who combine technical virtuosity with a relentless appetite for invention. Each has mastered a seemingly traditional medium—from painting to weaving to drawing—in order to take it somewhere entirely new.

Installation view of Nir Hod’s “The Life We Left Behind.” Courtesy of the artist.

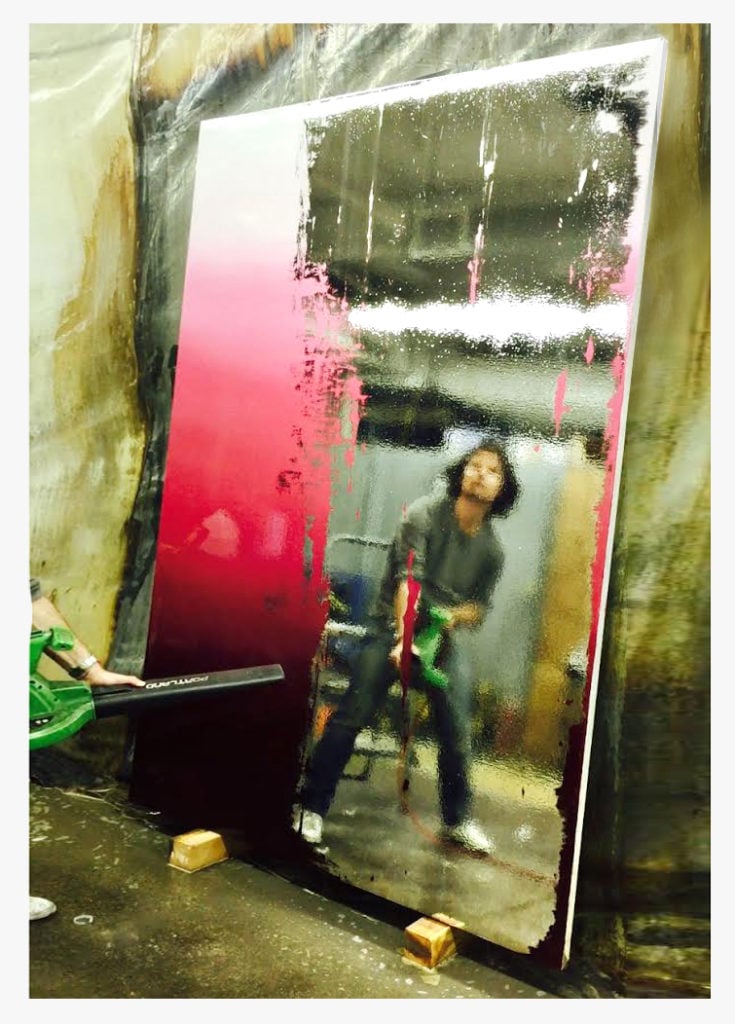

Nir Hod doesn’t do anything halfway. The Israeli-born, New York-based artist has been known to entirely overhaul the lighting system in his studio just to suit a new series he is working on. Right now, Hod is in the midst of a new body of work that fuses chrome with oil painting. The result is canvases that combine the overripe glamour of a Marilyn Minter photograph, the abstract forms of a Gerhard Richter painting, and the mystery of an antique mirror.

For Hod, these paintings are the next step in a career-long exploration of how to fuse luxury and beauty with violence and darkness. As Richard Vine wrote ahead of the artist’s survey at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, “from the beginning of his career, Nir Hod has opposed the ideology that labels sumptuousness an esthetic sin. His work openly substitutes the pleasure principle and a fluid multiplicity of selves for the old notions of high seriousness and personal authenticity.”

After studying at Bezalel Academy in Jerusalem and Cooper Union in New York, Hod began painting Pop-inspired flowers, self-portraits that embrace androgyny, and hyper-realistic-but-surreal paintings inspired by historic photographs. (An image of a former Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin and King Hussein of Jordan sharing a cigarette, for example, planted the seed for a series of paintings of world-weary children lighting up.)

Nir Hod, Mother and Genius Child.

After a concentrated period working in figuration, Hod has newly embraced a different kind of process as well as abstraction. Here, watch a 360-degree video of the artist at work, and read an interview about his innovative approach to making art.

You’ve said it was Gerhard Richter’s work that inspired you to dedicate yourself to the medium of painting, and your canvases often use a similar kind of dreamlike, abstracted photorealism to mine weighty subjects—in your case, topics like sexual identity and genius. Why do you think painting is a uniquely successful way to engage with big issues and questions?

It found me more than I found it. There is something so powerful about looking at an image in a painting—you just want to take part in it. Today, you see so many images every second—in advertising, on your phone. It makes me understand more and more the value of painting. You can’t compare a good painting to anything else.

Nir Hod in his studio. Photo: Nir Hod.

Your chrome-painting process is extremely unique. How did you develop it, and why did you need to take such a novel approach to achieve the look and feel you were after?

There is something really seductive about reflection. In a very simple, human way, it’s fascinating to see yourself. So I decided to chrome these canvases and compose in this violent or romantic way the paint underneath. It was important for me to push the craft in a new direction in this time when everything is so extreme.

There aren’t too many people in the world who can still do this process. From what I understand, it’s a process the navy invented in 1939 to chrome soft material that doesn’t involve any electrical plating. You start with oil on canvas—I paint from my imagination, but my studio is surrounded with images of landscapes, sites from history. When the paint is dry, I take it to another studio where the chrome is applied—that’s a process that takes a few hours. At first, it looks like black paint, but slowly it turns into a mirror effect. It’s like magic, even for me. The whole process takes between seven to nine days. Then I have three or four different ways to expose the paints underneath. One is extreme air pressure. That makes the surface look like an old patina on a building. I like it because it’s very accidental—I can control, like, 60 percent of it.

Art Collector Amy Phelan at the opening of Nir Hod’s “The Life We Left Behind” (2017–2018). Courtesy of Gavlak Los Angeles, Palm Beach

Another way to remove the chrome is to throw ammonia, which starts to heat the chrome but doesn’t do anything to the oil paint underneath. I can also scratch it by dragging the canvas up and down the road next to my studio. It creates a violence that feels so human. I like the relationship between beauty and destruction.

Your paintings oscillate between representation and seeming abstraction. What are the benefits of each approach, and how do they let you explore different themes?

It depends when you ask me, but sometimes even the chrome paintings look like realistic paintings—parts of a landscape reflected on a window or a billboard that got destroyed from the sun. Also, the surface always reflects the viewer and the architecture, so it becomes figurative at some point. They are abstract paintings, but I have all these references—from the “Shadow” paintings of Warhol to the light of J.M.W. Turner. It’s almost like to get lost in something abstract turns it into a representational image, and vice versa.

Installation view, Nir Hod, The Life We Left Behind. Courtesy of Gavlak Los Angeles, Palm Beach.

What are the most indispensable items in your studio, and why?

It changes. Every day, every week, I find something different that I’m obsessed with. The studio, for me, is something that changes. I recently moved my studio to Mana Contemporary in Jersey City from the Meatpacking District. I don’t have an attachment to anything in here except the work.

What is your studio-going routine?

I believe in routine. I go in every day to the studio around 9:30 a.m. and I stay until at least 7 p.m. I also work at night, but never at my studio. At night, I like to think. During the day, it’s very mechanic. The studio is a place for mistakes and interpretation, but in general, I’m just working. At night, I work in a different way. It’s more artistic. For me, a studio is a place where you make magic happen, but you don’t create it there.

Installation view of Nir Hod’s “Mother.” Courtesy of the artist.

What kind of atmosphere do you prefer when you work? Do you listen to music, talk to your assistants, prefer silence? Why?

I change everything—the lighting, the clothes I wear, the music I play—based on what I am working on. You can wear a jacket that makes you feel like a rockstar or a sweater that makes you feel like you want to stay at home and read a book. Sometimes I play music I don’t like to create a different energy. And when I started to work on the chrome series, I changed all the lighting in my studio to fluorescent. I hated that before—it reminded me of the hospital. But it’s part of the way I need to see my work.

How do you know when an artwork is finished?

Over the last nine years, every time I think a painting is done, I listen to the soundtrack of Schindler’s List. I don’t know why, but this kind of music makes me understand or feel if I’m right or wrong—if the work is done or not. I look at only that one work; I don’t look around the studio or compare. The work can be about the Holocaust or about chrome and the sublime—it’s always the same music. It provides the same filter.

Nir Hod, Red. Photo: Nir Hod.

When you feel stuck in the studio, what do you do to get un-stuck?

When I get stuck, I feel the need to go into the studio. So many people look for inspiration by traveling—but I travel in my mind. There were so many times that I knew I was stuck and I would try to continue by doing all these artist clichés—leave the studio, listen to different music. But it wasn’t working. At some point, I just started to destroy paintings—a little study or something. You discover so many things about fear—you have this fear to destroy something that you could sell or invest money in. But I always gain something out of it. It pushes me to the next stage. I think to be stuck is part of being a human, not just being an artist.