In the Studio

In the Studio With Julia Bland

See a 360-degree video of the New York-based artist Julia Bland at work as part of artnet's "In the Studio" series.

See a 360-degree video of the New York-based artist Julia Bland at work as part of artnet's "In the Studio" series.

Artnet News

To an outside observer, the creation of a work of art can seem like a magical process, with the artist dreaming up a concept and then transmuting it from pure ether into an inspired tangible object. But while the artwork can seem effortless when seen in its finished form, it is in fact the product of trial and error, honed skills, experience, and, in many cases, significant physical exertion—all taking place in the private laboratory that is the artist’s studio. Now, artnet News has teamed up with Dobel Tequila to present the “In the Studio” series, providing a rare glimpse inside this mysterious process with the help of 360-degree video technology. We chose artists who combine technical virtuosity with a relentless appetite for invention. Each has mastered a seemingly traditional medium—from painting to weaving to drawing—in order to take it somewhere entirely new.

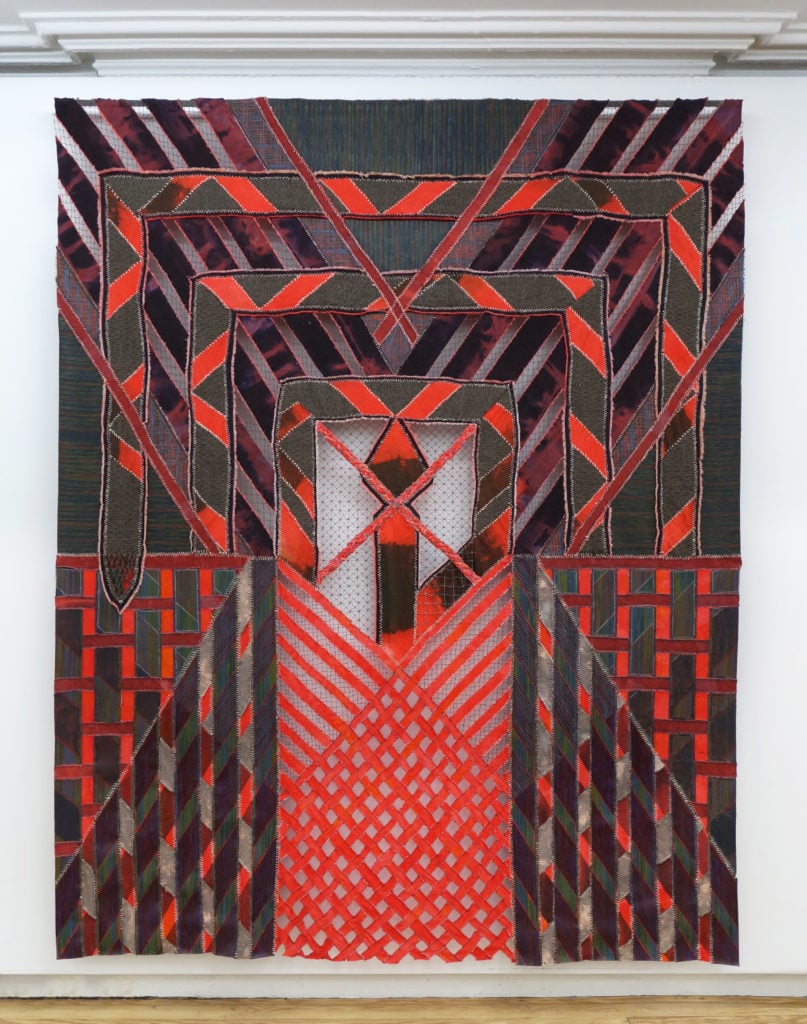

The artist Julia Bland makes artworks that exist somewhere in the space between painting, sculpture, and tapestry. Her experimental process incorporates stitching, weaving, knotting, dying, and even burning her materials. The results are gorgeous abstractions with geometric compositions that have tactile presence in the room.

A graduate of Rhode Island School of Design in Providence, where she earned her BFA in painting, and Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, where she got her MFA in painting and printmaking, Bland has had recent solo shows at New York galleries Helena Anrather—who is showing her work at NADA Miami this week—and Stellar Projects, the latter in conjunction with MILLER, now 17 Essex.

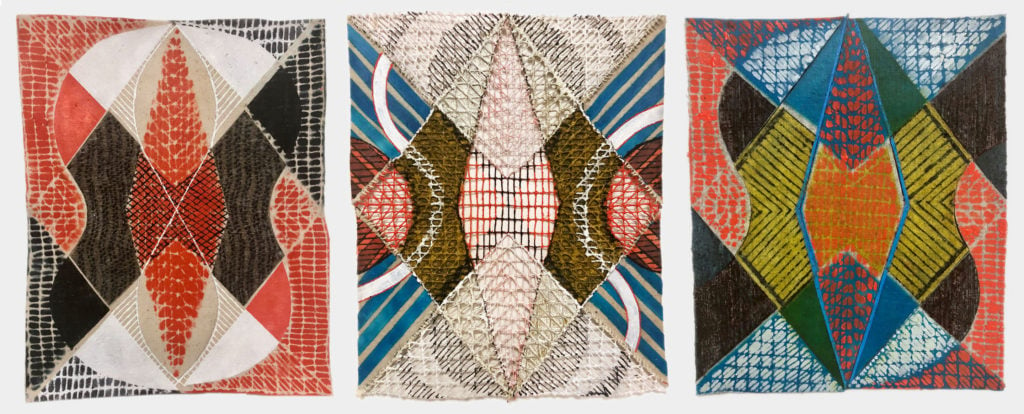

Julia Bland, Sway/ Split/ Sliver (2018). Courtesy of the artist.

While many artists who worked with fiber in the 1960s and ’70s eschewed the traditional loom entirely, Bland incorporates it as one of many tools—alongside her trusty scissors, and, of course her hands—to transform fabric into a transporting tableau.

Bland first became interested in weaving, patterns, and embroidery during a trip to Morocco 10 years ago, where she studied Islamic art and Sufism. The experience has embedded itself in her work, which often contains intricate geometric patterns that recall ornate Islamic architecture and images of snakes, a sign of death and rebirth in Sufism. Other forms in her paint-tapestry hybrids, meanwhile, resemble the suspension bridges of New York—a reminder that majesty can come from the spiritual world, the natural world, and the urban world all the same.

These days, Bland is hard at work in her Brooklyn studio, quietly honing her craft. By fusing two traditional artistic modes—painting and weaving—Bland works to create something imbued with history and yet fully her own. Here, watch a 360-degree video of the artist at work, and read an interview about her innovative approach to making art.

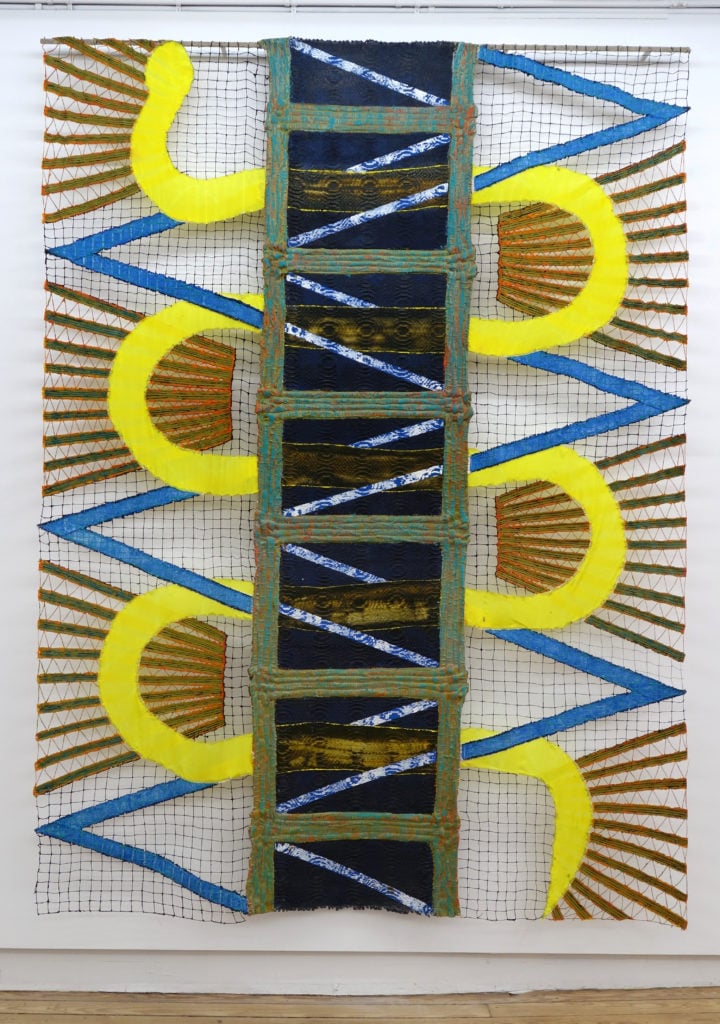

Julia Bland, Broken Clock (Twice A Day) (2016). Courtesy of the artist.

Tell me about the piece you are working on now—what is it, and is it intended for any particular show or destination?

I am working on a series of pieces that incorporate burnt canvas, weaving, and painting. The different processes produce their own shapes and textures, as well their particular relationship to time (duration). I want to create a strong sense of direction and light, as well as interior and exterior within each piece.

I am also working on some small pieces, which has been really exciting. The compositions develop quickly from one to the next, and I am able to explore a few ideas at the same time. These will be shown all together alongside the larger pieces in “Even Thread Has a Speech,” which is an exhibition of contemporary artists curated by Shannon Stratton in dialogue with “Lenore Tawny: Mirror of the Universe” at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center [in Sheboygan, Wisconsin] opening next fall.

What are the two or three most indispensable items/tools in your studio, and why?

I use all kinds of tools and materials and I love them all. But the thing that comes to mind is scissors. I have so many pairs, and I use them constantly in every stage of my work. They have a kind of silent presence, but they are behind a lot of the important moves and decisions.

When do you like to go to your studio? Then what is the first thing you do when you arrive, and why?

Most days I get to the studio at 10 a.m. It’s not too early but it still feels like morning, cool and quiet. When I first arrive, I just look around for a while. It’s a good time to let things linger and settle, figure out what’s happening and what needs to happen next.

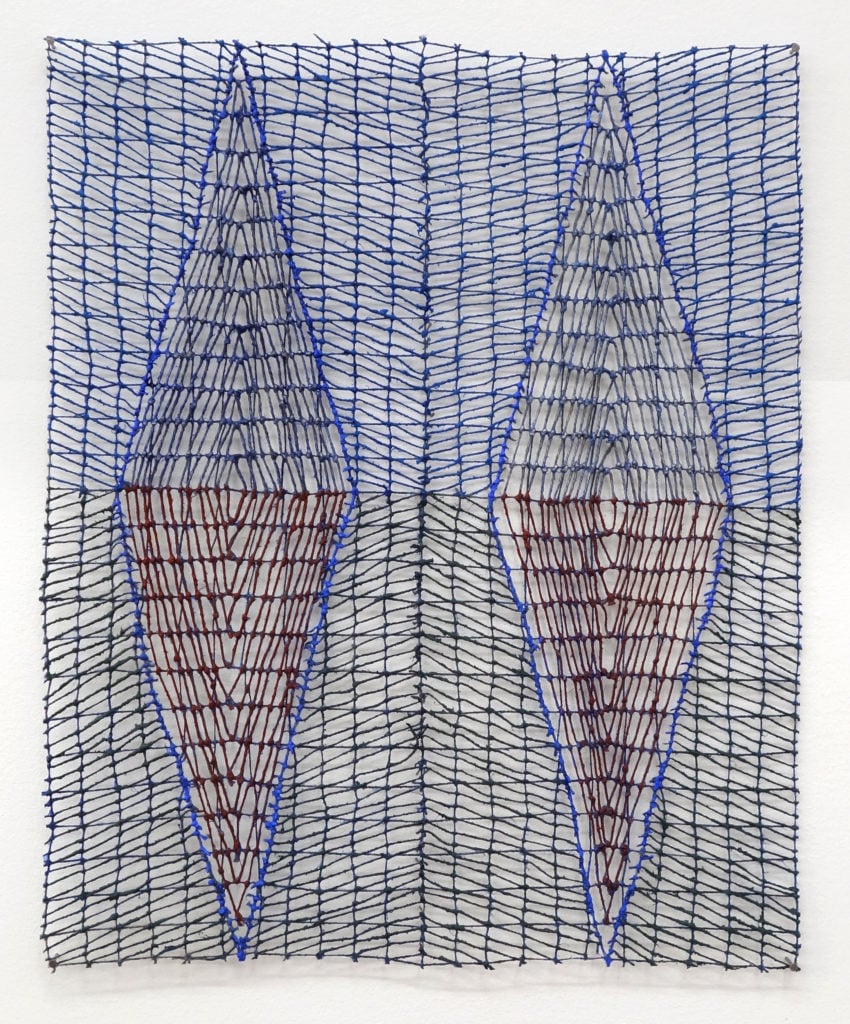

Julia Bland, Slow Rip (2017). Courtesy of the artist.

What kind of atmosphere do you prefer when you work? Do you listen to music, talk to your assistants, prefer silence? Why?

I like to work in silence; it makes the time seem long and that can be a good feeling. Usually at some point I turn on WNYC. I like the radio because you don’t have to think about it or adjust it. I can pay attention or tune it out; the sound of the voices keeps me moving.

How do you know when an artwork is finished?

I do lots of small drawings, thinking, and planning before I start a large piece. By the time I really get going, I have something in my mind I want to see. It’s like watching a dream come to life, step by step it appears. By the time I am done there is a feeling of recognition.

When you feel stuck in the studio, what do you do to get un-stuck?

If I look around and see too much of the same, I will begin by enforcing some kind of practical change. For example, last June I went away to residencies for the summer and didn’t bring any red or blue paint. It forced me to find another way of communicating temperature, as well as make me rethink color, light, and composition generally within a limited palate.

Julia Bland, Drink This (2016). Courtesy of the artist.

For a person encountering your work for the first time, are there any earlier artists, disciplines, or ideas that you believe they might benefit from knowing as context?

I love to read novels; a few that come to mind are To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf, The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov, and Frankenstein by Mary Shelley. Other things… listen to Bulgarian women’s choir music or walk across the Brooklyn Bridge.

What is your process for creating a work, from getting the idea to working it out to creating and mounting it?

A piece can start from a number of different places, from a certain compositional structure, physicality or weight, the time of day or year, a material process, or a memory. I keep a notebook and make lots of little drawings all the time. They help me think through my ideas, and they also function as a kind of map, with different marks indicating the process or material.

Every piece starts in a different place, some with the center, others at the edge. There is no clear order of operations. Something can be sewn and then painted, or painted and then sewn, or dyed then woven, or woven and then dyed, etc. This is part of the mystery, I love when the beginning and the end are intertwined and lost.