Art Fairs

6 Galleries Changing the Conversation at New York’s 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair

The fair serves to connect new audiences to African artists—but it opens new conversations around diaspora as well.

The fair serves to connect new audiences to African artists—but it opens new conversations around diaspora as well.

Melissa Smith

In the Côte d’Ivoire, Simone Guirandou-N’Diaye is known as “the mother of the artists.” The gallery she co-founded with her daughter Gazelle Guirandou is one of the 26 exhibitors at this year’s New York edition of the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair—which opened today at 439 West 127th Street, and will run through Sunday. Simone opened her first gallery thirty years ago in Abidjan, knowing, she once said, that the only way for artists “to flourish is to help them get in touch with the public.”

The phrase sticks in my head as a reminder of the importance of galleries in sustaining artists, both commercially and in terms of building a public for their work. Since the very first edition of 1-54 in 2013 in Marrakech, founder Touria El-Glaoui has been applying that same sentiment on an even bigger level, using her fair as a platform to boost galleries that sustain artists both from Africa and from its diaspora.

For the 2023 New York edition, El-Glaoui was very intentional in continuing to use the fair to “explore conversations around diaspora,” she told Artnet News. This aim manifests in a program of galleries showcasing work by artists based in the Caribbean, South America, the United States, or Europe. Below, I’ve spotlighted six spaces, including Guirandou’s path-breaking gallery, that demonstrate how 1-54 has taken the stories that live on the continent and put them in proximity with others that don’t—but often can be traced back to Africa, in one way or another.

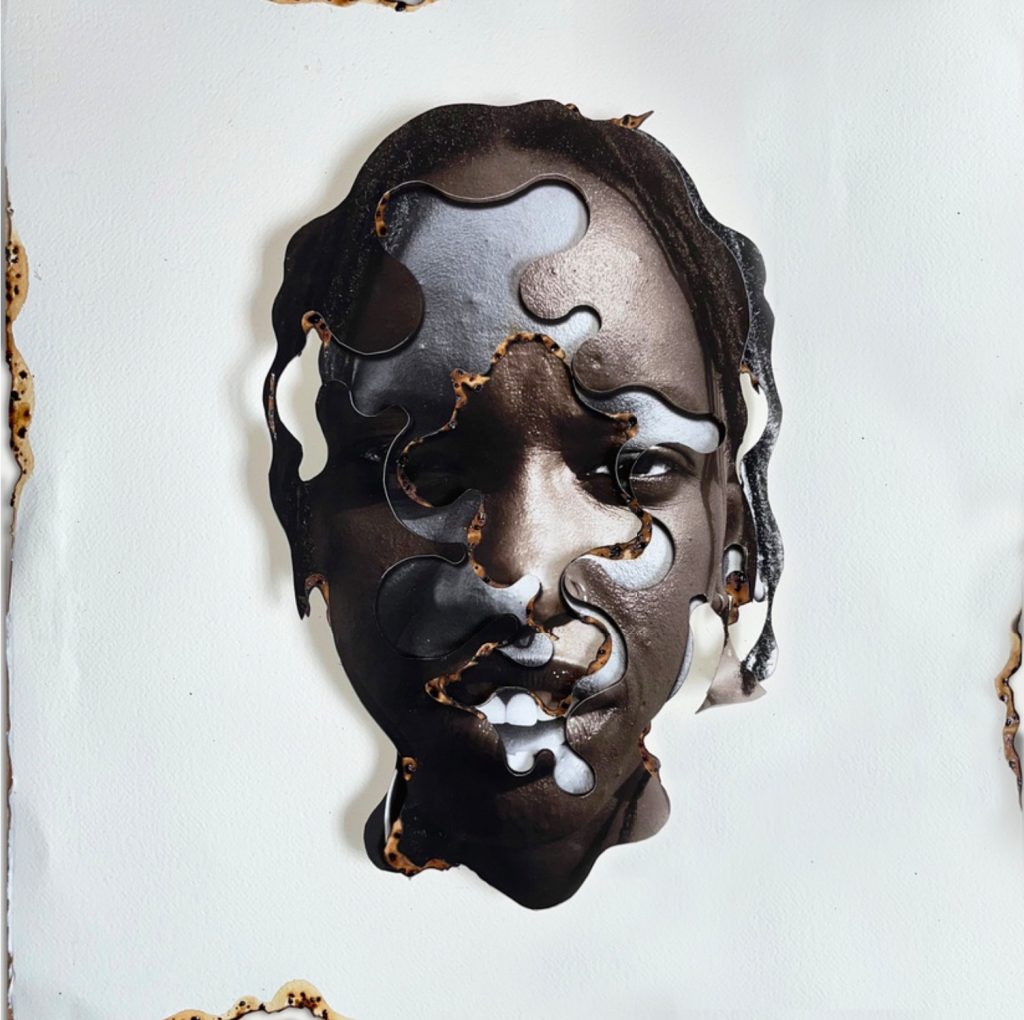

Pedro Pires, Mask for a future (2022). Image courtesy LouiSimone Guirandou Gallery.

A bright yellow wall piece hangs next to the entrance of LouiSimone Guirandou’s booth. Measuring 8-by-10-feet, it can easily be mistaken for a textile. The work is by Malian artist Ange Dakouo and is actually made with recycled newspaper that he’s wrapped over small squares of cardboard and then dipped in paint.

Once inside Guirandous’s stand, the thickly painted gestural works by Ghanaian professor and painter Ablade Glover seem to jump off the wall. Feeding off that energy, in the center of the booth are lightweight fiberglass busts by an artist named Pedro Pires, who splits his time between Angola and Portugal. He’s covered the heads with traditional African wax fabrics, referencing how these have become symbols in his hometown of Luanda, Angola, where they’re often one of the the first things people see.

Works by Isabelle.D and Caio Marcolini at Gallery Nosco. Photo courtesy the Gallery Nosco.

There are a lot of vibrant displays throughout 1-54—but none quite like Gallery Nosco’s booth full of large, crocheted canvases by French-Algerian artist Isabelle.D. The Algerian artist’s works look like lush, colorful floral gardens sprouting from the wall.

Despite appearances, though, they were not inspired by nature. In fact, the artist made them to mimic the coloring of a bruise. So hiding behind the splashes of rich reds and blues is an analogy for how colonization has injured or bruised societies.

Paired with these are metal sculptures by Brazilian artist Caio Marcolini. Using a single-wire weaving technique that is traditional to Western Africa, Marcolini’s amoebic pieces look like they’re suction-cupped onto the wall—and yet, somehow, they appear fragile at the same time, as if they might unravel right off of it too.

By the end of VIP day, all of Marcolini’s pieces, which were priced from $2000 to $8000, had been sold. Isabelle.D’s works were priced between $18,500- $50,000 and only one remained at the close of day one.

Roland Dorcély, The Mill from the Path (ca. 1958). Image courtesy Loeve&Co.

In the mid 20th century, Haitian artist Roland Dorcély was living as an artist and poet in Paris, socializing with some of the great artists of the time, from Roberto Matta to Pablo Picasso. His paintings strongly evoke that influence, with flat, contoured lines separating deep blocks of color.

And yet, he struggled to find success. He once wrote to one of the few supporters of his work that people in Paris expected him “to wear a loincloth, a quiver and arrows, but not to like Winslow Homer or Seurat.” By 1962, he had fallen so far into debt that he had to sell his work to his Parisian dealer—and leave Europe for good.

Loeve & Co. discovered the work decades later after a meeting with the grandson of that dealer. The gallery recently sold a large piece to the Centre Pompidou, five years after Dorcély died in 2017, having lived most of his life in complete obscurity.

Prices for Dorcély’s smaller works start at $15,500, with the largest piece going for $41,000. They are all still available.

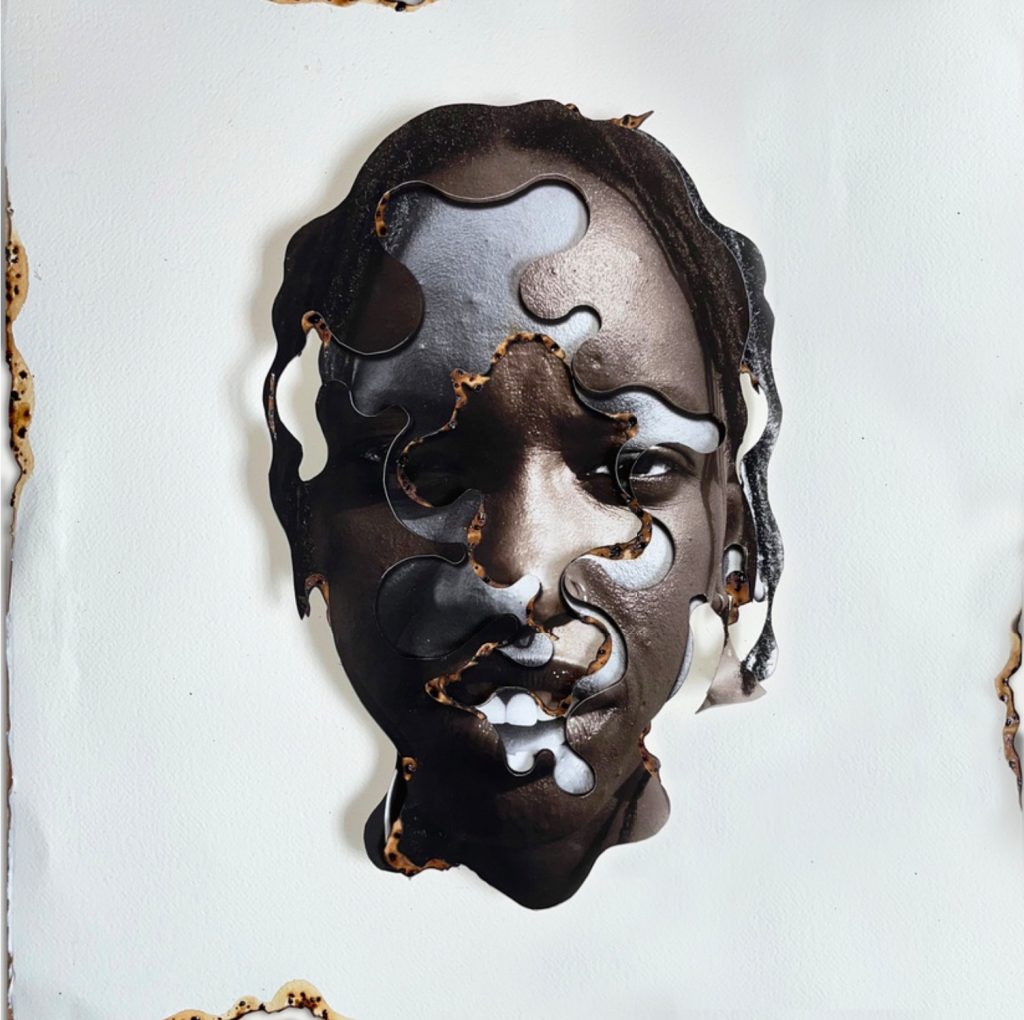

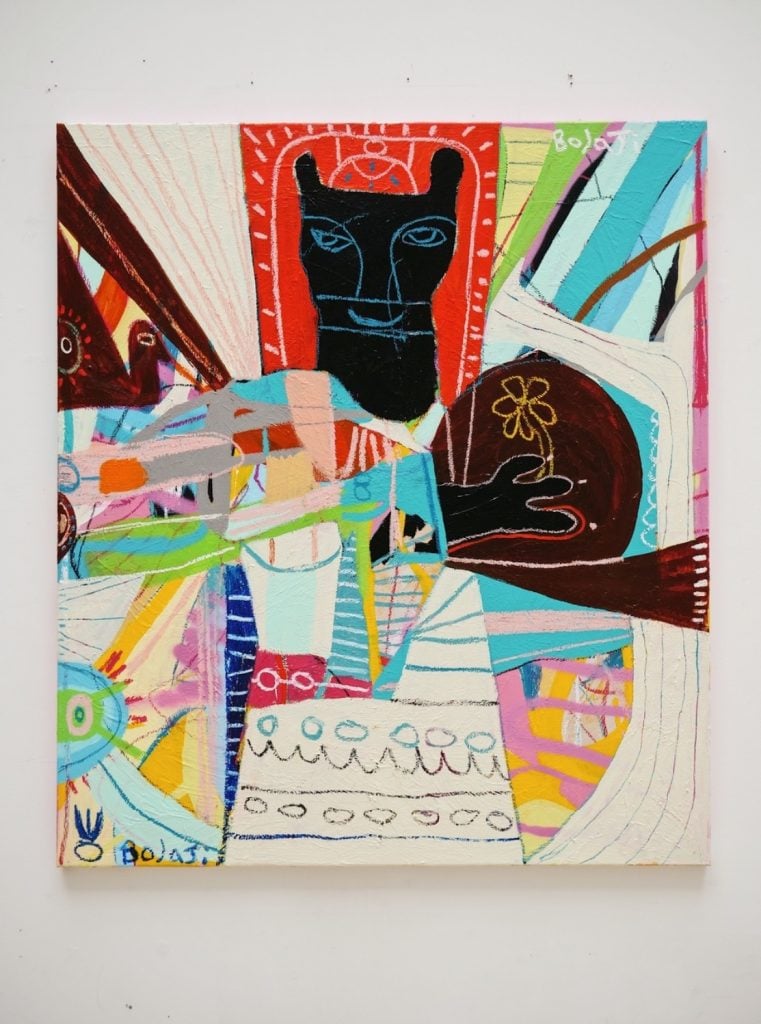

Adébayo Bolaji, Aago (2023). Image courtesy kó.

Many of the works at the fair contain double or hidden meanings related to either colonialism or the political turmoil left in its wake. A ceramic piece looking like a large garment hangs from one wall of kó’s booth. Oziomo Onuzulike made it with ceramic palm kernel beads that were employed “once as a symbol of currency in West Africa, and then transformed in more contemporary times as a symbol of social status,” explained kó director Joseph Gergel.

On the opposite wall, Nigerian artist Mobolaji Ogunrosoye created the collaged portraits on display by manipulating photographs she’d taken of her friends. These distortions are meant to remark on perceptions around the female body in Nigeria.

Finally, sandwiched between these works are colorful large-scale paintings by British-Nigerian artist Adébayo Bolaji, who takes old Yoruba parables or stories and shapes them into new stories, via the deft interplay of figures and symbols.

Ogunrosoye’s portraits are available and priced at $4,000 a piece. Onuzulike’s garment costs $40,000, and Bolaji’s paintings are priced roughly in the middle at $18,500 a piece.

Jared McGriff, In the Shallow Cool in Between (2022). Image courtesy Spinello Projects.

One of the more interesting elements of the fair this year is seeing how work by emerging African-American artists fits in.

One example: At Spinello Projects’s booth, Jared McGriff’s figural works, painted with loose and choppy brushstrokes, play with the themes of memory and intergenerational labor. All of his paintings, which range in price from $12,000 to $55,000, were sold by the end of the preview day, following some notable recent acquisitions by the Hort Family Collection and Jasteka Foundation.

Works by Josie Love Roebuck at LatchKey Gallery. Image courtesy LatchKey Gallery.

Another standout among African-American artists at 1-54: At LatchKey Gallery, the textile portraits by Josie Love Roebuck, which center around the idea of belonging—or the lack thereof.

In I know why the southern black girl sang, her piece that reimagines Degas’s Little Dancer, Roebuck attempts to reclaim the space she never thought she had, growing up as an adopted mixed-race child in Chattanooga, Tennessee, and looking to understand who she really was.

The prices for her solo booth range from $2,000 to $12,000, with three sold and two on hold at the end of VIP day.