Art Fairs

‘African Art Is Here to Stay’: Collectors Were in a Buying Mood at the London Edition of the 1-54 Fair

The fair that helps launch artists' international careers gives collectors ahead of the African art curve reasons to feel smug.

The fair that helps launch artists' international careers gives collectors ahead of the African art curve reasons to feel smug.

Naomi Rea

Art collectors love to be ahead of the curve, especially when a market is “emerging.” African contemporary art is in demand but prices are still within the reach of even new collectors. In London, the sixth edition of the pioneering African art fair 1-54 attracted new and established collectors as well as curators from prestigious institutions such as LACMA, the Guggenheim, and Fondation Louis Vuitton. Celebrities drawn to the event included the actor Idris Elba.

Around 18,000 fairgoers flocked to Somerset House during Frieze week in the hope of discovering artists, some of whom might become market darlings, or even superstars. The Nigerian artist Ben Enwonwu, who showed at the fair in the past, saw his auction price soar when his so-called “African Mona Lisa” painting fetched $1.67 million at Bonhams in February.

Speaking at the fair, Othman Lazraq, the president of Morocco’s new museum of African contemporary art, MACAAL, and director of the city’s cultural nonprofit, Fondation Alliances, told artnet News that collectors should be buying because of passion. He acknowledges that it can be a sound investment, however. “People who bought African art a long time ago are really lucky because the market is now established,” he said. “African contemporary art is not a trend” he stressed. “It is here to stay.”

Lazraq, who is on Tate’s African art acquisition committee, comes from a family of collectors. When his father, the property mogul Alami Lazraq, began collecting contemporary African art 15 years ago, there were just a few galleries dealing in art from the continent, and none specializing entirely in contemporary African art. Today it is a different story. At the fair, 43 galleries from Africa, Europe and North America presented works by more than 130 artists based on all three continents and beyond.

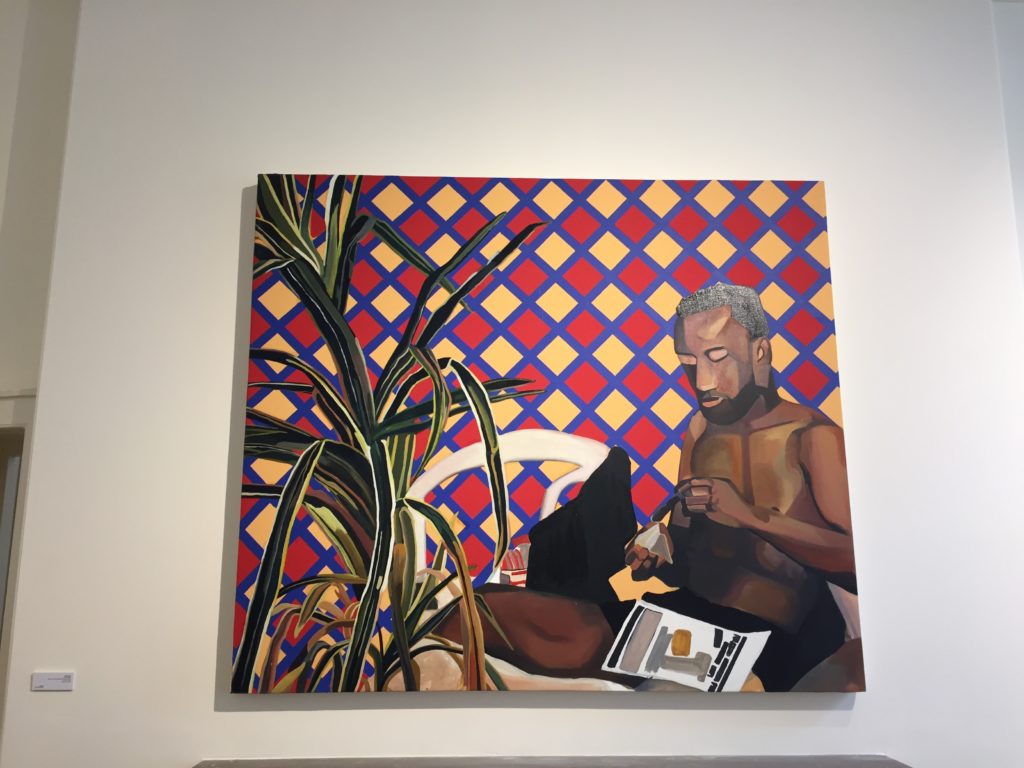

Joy Labinjo, Untitled (2017) in Tiwani Contemporary’s presentation at 1-54. Photo by Naomi Rea.

Lazraq was acquiring work for MACAAL on the opening day of the fair, and picked up a 2017 painting by Joy Labinjo, a young British artist with Nigerian heritage, for around £7,000 (around $9,000) from Tiwani Contemporary—which he points out was one of the first galleries to show US artist Kerry James Marshall, who was in London last week for his show at David Zwirner.

The fair has grown with the market. Launched in 2013, 1-54 now has a Marrakech edition and is expanding in New York, relocating from Brooklyn to a venue in Manhattan’s West Village for its fifth anniversary in May 2019. It has also launched artists’ international careers. The British-Caribbean sculptor Zak Ové’s 2016 courtyard installation, Black and Blue: The Invisible Men and the Masque of Blackness sold from the fair for £300,000 ($391,000), and the UK-based Vigo Gallery was showing his work this year next to the most expensive work in the fair, a £1 million ($1.3 million) painting by Ibrahim El-Salahi, whose work is in the collections of MoMA, the Met, and the Tate. The Sudanese artist was presenting his first foray into sculpture in the courtyard this year, the three trees were a talking point of the fair just like Ové’s installation was two years ago. Editions of Ovés invisible men are now on show in San Francisco’s Civic Center Plaza and Yorkshire Sculpture Park in the North of England.

Installation shot of Addis Fine Art’s presentation at 1-54. Photo courtesy Addis Fine Art.

Galleries at the fair were rehanging their presentations in Somerset House by the end of the preview day on October 3. London- and Berlin-based gallery Kristin Hjellegjerde, which was making its fair debut, sold all 12 pieces by the Ethiopian artist Ephrem Solomon which were priced at $7,000 each (Solomon’s 2013 The Unknown Lady also sold for $6,851 at Bonhams’ Africa Now sale on October 4), and a piece Dawit Abebe for $17,000. A delighted Hjellegjerde told artnet News that her stockroom was now “depleted.”

The Ethiopian gallery Addis Fine Art also sold out of all the works in their booth by the end of the opening day with prices in the range of £5,000 to £10,000 ($6,500 – $13,000). Milan’s Primo Marella Gallery, which, founded in 1992, was one of the more established galleries at the fair and has been researching the market on the continent since 2008. The gallery was selling work by established artist Abdoulaye Konaté (whose auction record is $48,352) side-by-side with abstract collages by emerging artist Januario Jano priced between £5,500 and £10,000 ($7,000 – $13,000). The gallery also placed a sculpture by Ifeoma U Anyaeji featuring upcycled plastic bags sourced from Benin City’s roads in “an important Brazilian collection.”

Primo Marella’s presentation at 1-54. Photo ©Katrina Sorrentino.

Mega-collector Rita Sigg, wife of Uli Sigg, was spotted at the fair, as well as African art collector Serge Tiroche. Vanessa Branson, sister of billionaire entrepreneur Richard Branson, who founded the Marrakech biennial, told us, “It’s the beginning of that wave. You can feel it.”

That said, the prices for these works don’t come close to those being achieved at international contemporary art fairs like Frieze London. Fair director Touria El Glaoui said, “It doesn’t do us any favors to talk about prices” but she did point out that there have been larger pieces selling over the years, and that some of the artists at the fair had increased their prices by 160 percent since 2013. “It still leaves them in a very affordable ballpark but in terms of how fast they grew, it’s quite incredible.” She is proud of the way the fair has helped artists, who have been undervalued for too long, gain visibility, new collectors, and institutional recognition.

Speaking at the fair, Sotheby’s African art expert Ashkan Baghestani, told us: “I think it’s a very exciting time.” The auction house created an African art department in 2016. He points out that a growing number of institutions have major collectors on their African art acquisition committees. “In our markets, emerging markets, unless institutions take the real time to invest energy resources and research into these markets, nothing will be done. And since they are doing it, I think it’s a real pivotal shift.”