Art Fairs

10 of the Most Remarkable Artworks at the 2018 Armory Show

There's plenty to be absorbed by in this year's satisfying edition of the New York fair, the first under new director Nicole Berry.

There's plenty to be absorbed by in this year's satisfying edition of the New York fair, the first under new director Nicole Berry.

Andrew Goldstein

In its debut under new director Nicole Berry, the Armory Show did not seem to miss a beat in its tumultuous change of leadership but instead seemed to pick up some jazzy new rhythms, a thoughtfully slower tempo, and a scattering of lovely melodies. Brighter carpeting on the floors and airier aisles brought on by fewer booths lent an upbeat sensibility to the proceedings on the New York piers, sweetening ones spirit of discovery. And there were plenty of gems to find in the fair’s nooks and crannies. Here are some of the most absorbing artworks in this year’s edition.

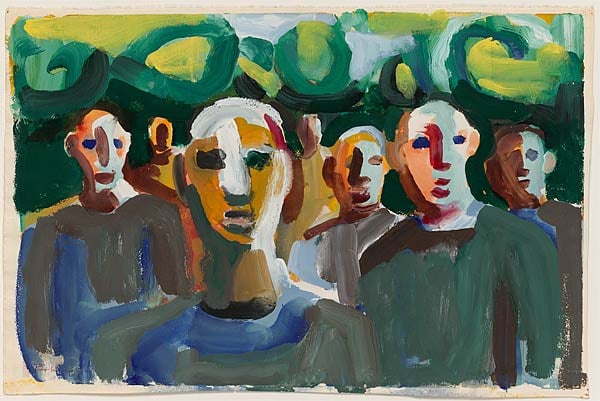

David Park, Crowd of Seven (1960), around $400,000. Courtesy of Hackett Mill.

Originally an Abstract Expressionist painter under the stylistic thrall of Clyfford Still, the San Francisco artist David Park gave up abstraction when he turned 40 and instead became a principal figure in the Bay Area Figurative movement alongside painters like Richard Diebenkorn and Elmer Bischoff. To break new ground, those three friends held weekly drawing sessions in which they would each set down figures but strictly from memory, which in turn yielded up a moody impressionistic style of painting that was at the same time distinctly American, reminiscent of Edward Hopper. When he turned 49, however, Park was stricken with a fast-moving form of cancer, rendering him so weak in his final three months that he could only work in gouache on paper, and then only when refused his pain medication.

This work on paper is representative of the spectral portraits he created immediately before his death in 1960, carrying over his forceful economy of movement—a single white slash for a nose, for instance—while setting a haunting elegiac tone. Today, Park’s renown trails Diebenkorn by a long shot (and his highest price at auction is $2.7 million range, versus Diebenkorn’s $13.5 million), but that may be in the process of changing: the curator Janet Bishop is working on a major retrospective of Park’s work at SFMoMA, his first such survey since his 1989 Whitney exhibition.

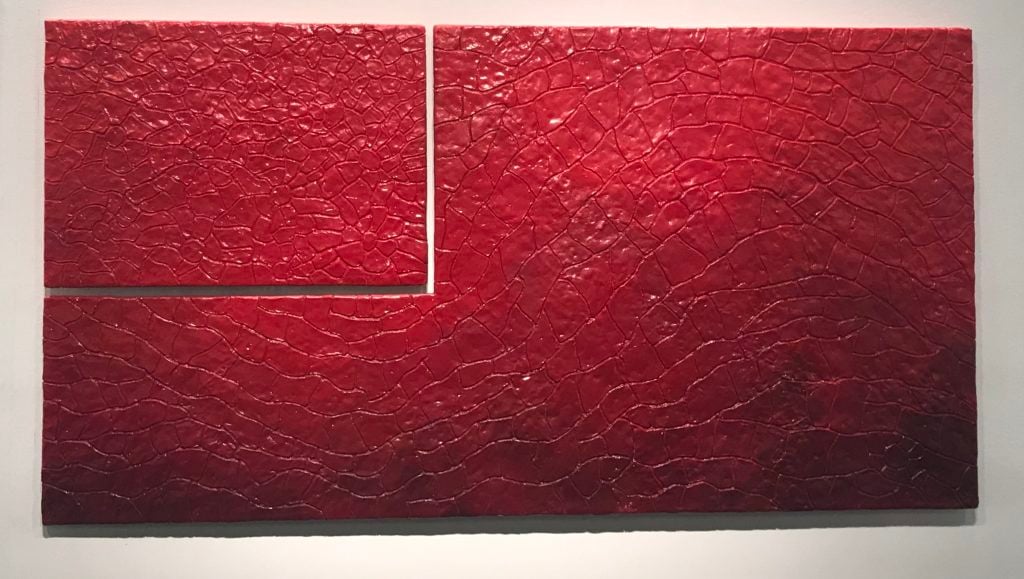

Ajay Kurian, Flag (Flowers of Evil) (2017), $12,000. Courtesy of Sies + Höke, Düsseldorf.

Toward the end of last year, the artist Ajay Kurian staged a knockout show in Sies + Höke’s Düsseldorf gallery called “American Artist,” which unpacked some of his pessimistic thoughts about his country’s soul, and which opened on the heels of his inclusion in the biennial at the Whitney Museum of American Art. All that Americanness lingered with Kurian when he returned to New York, and he channeled it into a poetic new series: sculptures of the US flag, only with the cracked red skin of a chameleon instead of stripes, and, in this work, 13 flowers instead of stars (one for each of the original colonies). The notion of the United States as a chameleon, always changing and adapting the hue of its skin to new situations, is an apt gloss on the country’s character in these tumultuous times of identity battles, and perhaps even an optimistic one.

Park Hyun-ki, Untitled (1978), in the $150,000 to $200,000 range. Courtesy of Gallery Hyundai, Seoul.

Born in 1942, the pioneering Korean video artist Park Hyunki first saw a reproduction Nam June Paik’s work (specifically Global Groove) in 1974 in a library in his hometown of Daegu, and he was soon off to the races, participating in that year’s Daegu Contemporary Art Festival and gaining national renown. The way Hyun-ki used video in his work, however, was very different from Paik’s celebration of technological advances—instead Hyun-ki simply incorporated it as another element in his art, interchanging it with natural elements to comment on the boundary between reality and illusion. Meanwhile, to transcend the boundary between avant-garde activity and income, he worked on the side as an in-demand interior decorator, furnishing apartments in the high-rises then springing up all over South Korea in order to fund his art.

This installation shown at the fair was first debuted in the 1979 Biennale de Paris, where Hyun-ki gathered the stones from the surrounding countryside and then returned it to nature after the show, as was his practice. These rocks, then, come from his estate’s warehouse, as did the TV that charmingly pretends to also be rocks. A sly standout at the fair, it drew attention at the vernissage from such eminences as the collector Leon Black, who took his time lingering in front of the meditative piece.

Yayoi Kusama, Bird (1980), $300,000. Courtesy of Omer Tiroche Gallery, London.

When she was living in New York during the 1960s, Yayoi Kusama entered into an intense though platonic romance with the reclusive artist Joseph Cornell, and when he died in 1972 he left her a shoebox filled with his precious clippings from nature magazines—the birds, insects, and other animals that he famously used in his surrealistic so-called Cornell boxes. Devastated, Kusama moved back to her native Japan in 1973 and, in 1977, checked herself into the hospital where she lives and works to this day.

A few years later, however, Kusama took out Cornell’s shoebox and, in homage to her late lover, began turning the clippings into collages, centering them on monochrome paper and ringing them with her own signature “infinity” nets and dots. In total, she made about 150 of them, selling many of them to Japanese collectors, and for the past five years the enterprising London dealer Omer Tiroche has been painstakingly buying them back. Displayed as a partial set for the first time at the Armory Show, the diminutive collages line the wall of his booth, drawing in a steady stream of intrigued collectors.

Willem de Kooning, Untitled (circa 1971), $850,000. Courtesy of Hollis Taggart Galleries, New York

A grade-A de Kooning can be found at Hollis Taggart’s Armory booth for under $1 million, which is good news for collectors. Painted in sumptuous colors on two pieces of paper that the artist taped together, the piece is a visual postcard from the paradise of his life in the Springs, combining the luscious flesh colors known from his earlier “Women” series with the greens of the countryside. A satisfying explosion of seductiveness, it’s quite a bit pricier (by more than half) than the sums other works on paper from the period have commanded at auction, but paintings of similar beauty from the time go for multiple millions, and this is basically a painting in terms of oomph.

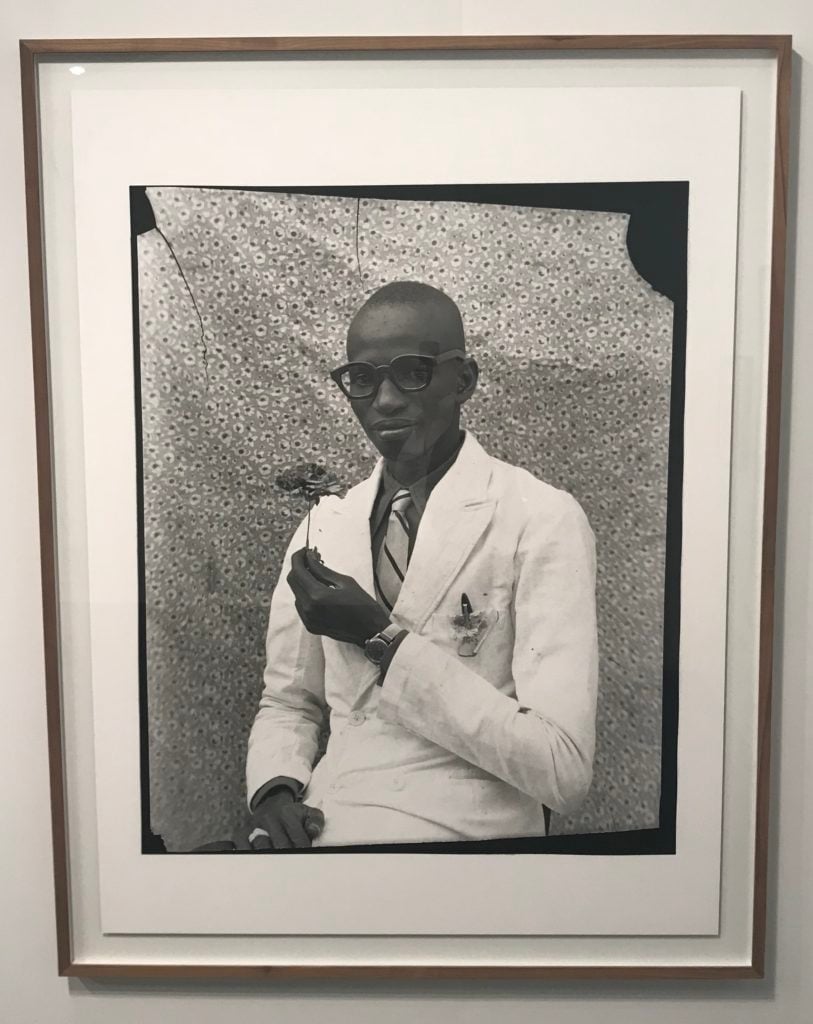

Seydou Keïta, Untitled (1958–59), $28,000, or $7,500 in a smaller format. Courtesy of Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris.

A self-taught photographer, Seydou Keïta gained renown in Mali for the photography studio he ran in Bamako, taking dignified portraits of his fellow Malians in modern (read: Western) attire and finery in a way that captured the country’s renewed sense of pride in the era of decolonization. In 1962, Keïta was appointed as an official photographer for Mali’s government, but after retiring in 1977 he receded from the limelight until, some decades later, the voracious photography collector Jean Pigozzi happened upon a box of his photographs and was entranced.

Pigozzi enlisted the legendary photographer and Bamako native Malick Sidibé if he knew where they could find Keïta, and the two tracked him down, allowing the collector and frequent curator to spread his name in the West in the years before Keïta died in 2001. Now his photographs are drawing admiring glances at the Armory Show, where his posed studio photographs like this one transcend their era: delicately holding a single flower, the bespectacled young man in the dapper double-breasted white suit exudes both affluence (though the rings, pen, and possibly clothes were provided by the studio) and the kind of contented dignity you see in Bronzino’s Florentine noblemen.

Hans Hartung, T198-E29 (1989), $450,000. Courtesy of Setareh Gallery, Düsseldorf.

Hans Hartung executed this painting, made in the last year of his life, in the same way he made most of his late paintings: sitting in a wheelchair (the result of a debilitating 1968 stroke) and using compressed-air spray guys, one for each color, to shoot paint onto the canvas. An artist who had been making abstractions from early on—there’s a story that Mark Rothko was a figurative painter until he visited Hartung’s Paris studio in 1946 and got inspired—his work is looking quite fresh these days, and has benefited from a hearty push on the part of a cabal of dealers who have been marketing him to Asian collectors and Westerners tired of recent, often-voulu abstractions and hungry for historicity. Hartung’s boosters are in luck: the Pompidou will soon give the artist a retrospective, according to Setareh Gallery, lifting his newfound renown (and, likely, his growing prices) even more.

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Pareidolium (2018), $160,000. Courtesy of Galería Max Estrella, Madrid.

No, not a hot tub, Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s centerpiece in curator Gabriel Ritter’s “Focus” section is actually a high-tech camera of sorts that uses facial recognition software to create a rough portrait of anyone who engages it by standing in a specific spot—not through film but by jets of cold vapor that spout, Bellagio-style, from the basin. The resulting images, which make anyone look a bit like the Misfits logo, hovers in the air only momentarily, but is also captured in a screen on the wall. Fair-goers crowded around the strange spectacle of the work, which the artist—who has a show at the Hirshhorn in October and at SFMoMA next year—has considered expanding into a 90-foot-wide pool.

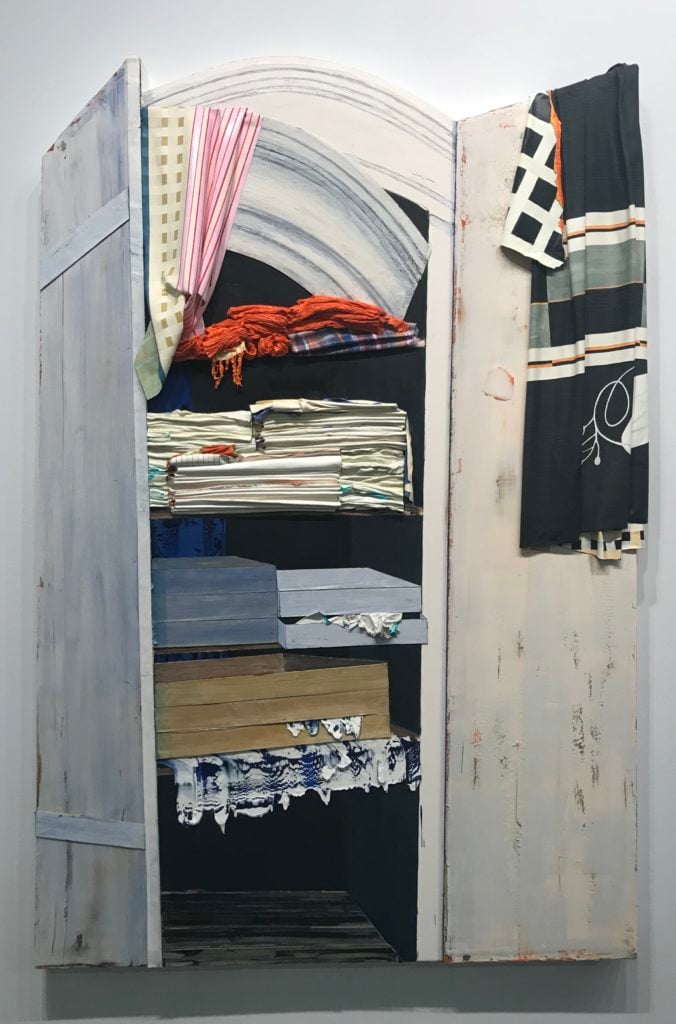

Leslie Wayne, Heirloom (2017), $58,000. Courtesy of Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

It took the painter Leslie Wayne years and years to perfect her unique style of layering acrylics and oils until they become objects themselves—and not merely trompe-l’oeil ones—by convincingly imitating draped fabrics and boards of wood. However, while she was able to pull off individual objects convincingly, she never managed to make a larger painting that could fuse her motifs… until now.

Considered a breakthrough piece, her painting at the fair replicates a linen closet overflowing with sheets and draped with blankets, with a blue substance that could might be water coursing through its middle, as if from a catastrophic water-pipe rupture. Wayne likes to depict thresholds in her art, and now that she has a solo show of this new body of work in preparation (and an Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum show to boot), her career may be in a liminal state as well.

Roxy Paine, Meeting (2016), $325,000. Courtesy of Paul Kasmin, New York.

With the same calm yet unsettling aura of unstinting observation that you find in a Frederick Wiseman movie, Roxy Paine’s diorama-like sculptures present environments of control, from his bravura recreation of a TSA checkpoint made entirely from wood to his rendition of a hotel room being monitored by CIA agents as part of a covert LDA experiment. At the Armory Show, Paine presents a banal-seeming meeting room that he’s rendered in disorienting forced perspective, so that to the viewer standing directly in front of it a few feet back sees a near-photographic-quality representation, while standing a few steps to either side shows the synthetic-clay-sculpted components to be hopelessly skewed.

What’s so weird about a meeting room? With chairs arrayed in a circle in the middle, it could be set up for an AA meeting or a group-therapy session, but for the cryptic messages on the blackboard: “Captives and Fugitives,” “places of captivity,” “constriction,” “retention,” “inability.” Whoever the room is waiting for, they’re mulling some dark stuff, and we’ll be there watching them through the implied one-way glass.