Art Fairs

Meet the East Village Bird Artist Bringing a $125,000 Pigeon Coop to Frieze New York

The classic work will be stocked with eight pure white pigeons.

The classic work will be stocked with eight pure white pigeons.

Sarah Cascone

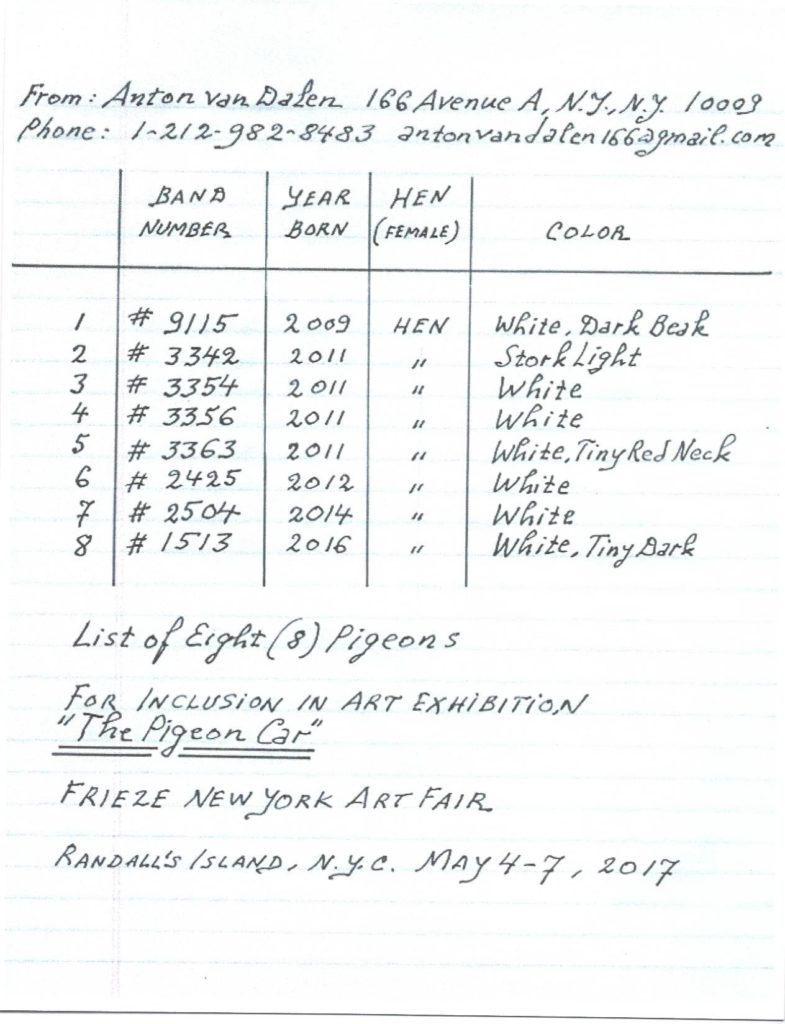

Bird lovers have an extra reason to take note of Frieze New York this year. As part of its booth at the Randall’s Island art fair, New York’s P.P.O.W. gallery will present an artwork by Anton van Dalen stocked with eight live pigeons, all pure white.

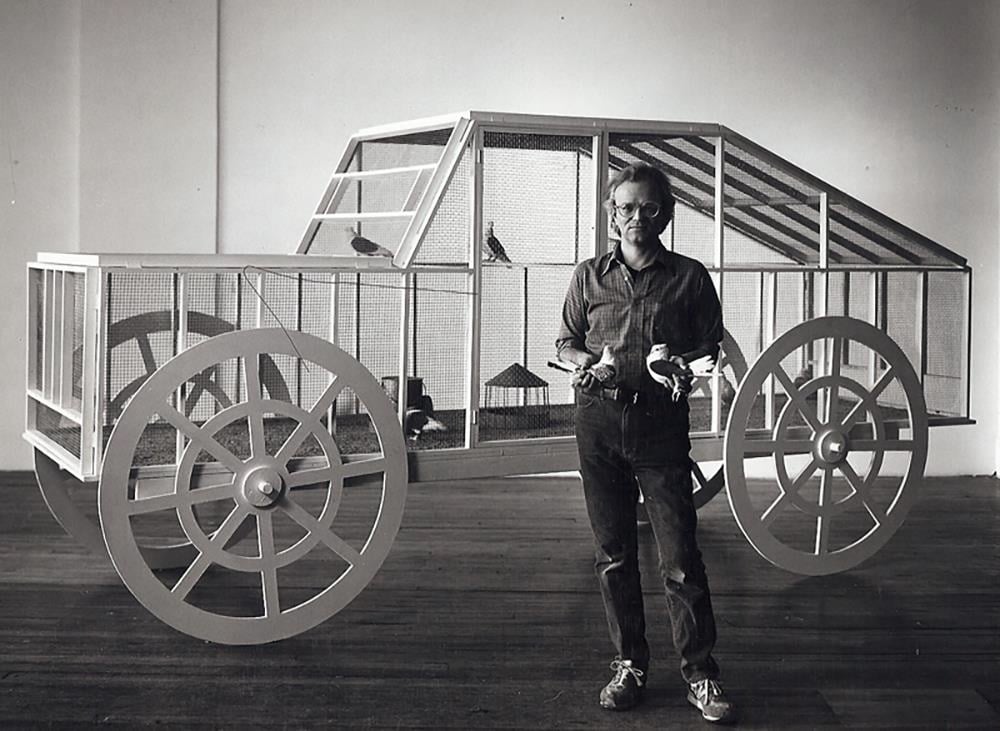

The birds will live in the big white Frieze tent for the duration of the fair (May 4–7, 2017) housed in The Pigeon Car, which is pretty much exactly what it sounds like: a large car-shaped sculpture/pigeon coop. The piece was made for a 1987 exhibition, titled “Immigrants and Refugees: Heroes or Villains?,” at New York’s Exit Art, an alternative art space. It was shown a handful of other times in the decade that followed, and again at New York’s Sargent’s Daughters in 2016.

The view pigeon coop on Anton van Dalen’s roof. Courtesy of Sarah Cascone.

At Frieze, the work will be sale for $125,000—pigeons not included, although the artist is happy to provide tips should the buyer be interested in activating the work. For the fair, Van Dalen is stocking the installation with his own prized birds, of the Tippler variety, bred over the years to have the whitest feathers possible. They are considered “High Flyers,” because a flock will fly high into the air when released into the sky.

A longtime member of the Flying Tippler Society of the USA, Van Dalen has loved pigeons since he was a child, and has a coop on the roof of his home and studio in the East Village, where he has lived since 1971. It’s one of the last remaining coops in the neighborhood.

Anton van Dalen with The Pigeon Car in 1987. Courtesy of P.P.O.W.

The artist immigrated to the US as a child after World War II. “We lost our home, the Germans took it over, [and] we became refugees,” Van Dalen told me during a recent visit to his studio, recalling hiding in the basement during bomb scares. Forced out, his family moved to a farm, a welcome respite from wartime fears. “That for me was totally magic, being exposed to domestic animals.”

“The birds have really been my life since I was a child,” he added. “Some people might call it an escape; I think of it as a parallel universe.” He finds the pigeon—common subject in his paintings and drawings—a useful image in his work because the dove is a well-known symbol of peace.

“These birds unite immigrant communities,” added P.P.O.W. co-founder Wendy Olsoff, noting that they are also “trained as carrier pigeons to send messages from one country to another.”

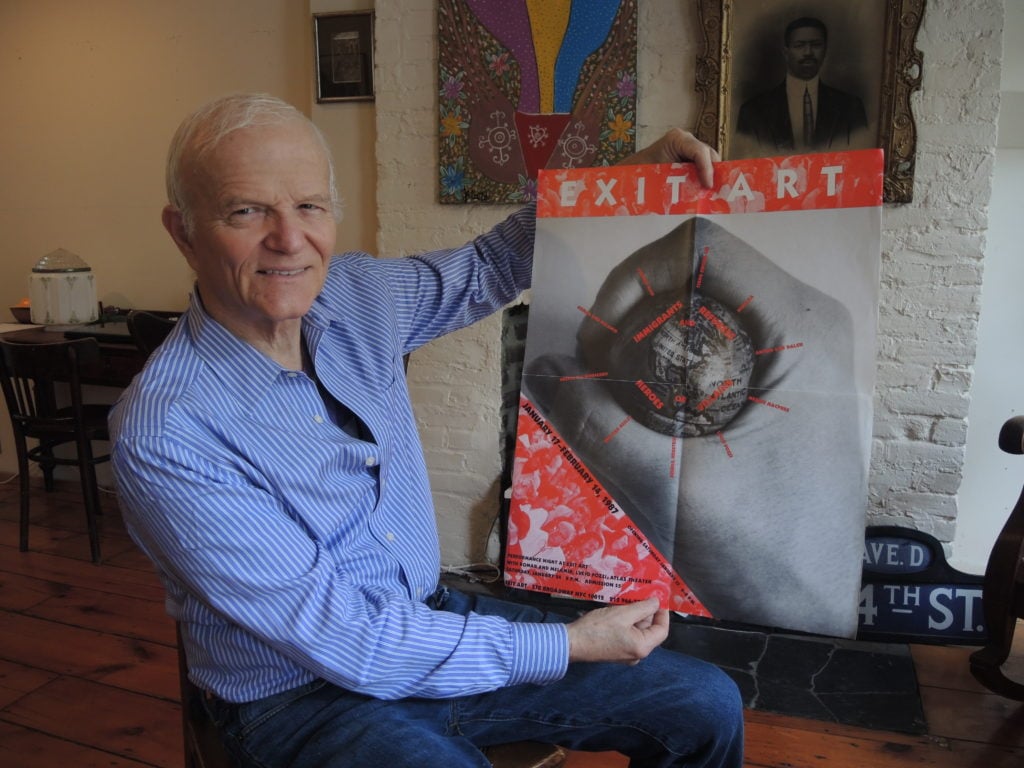

Anton van Dalen with the original poster for the Exit Art show where The Pigeon Car debuted in 1987. Courtesy of Sarah Cascone.

As The Pigeon Car celebrates its 30th anniversary, Van Dalen says he is unsurprised that it never sold. He originally showed it at Exit Art because “if you went to a gallery they’d be like ‘What the fuck, how am I going to sell this thing?'”

“There was a whole world of art that was not accepted in the mainstream art of the time,” he explained. Minimalism was the style of the day, rather than anything with a personal image or recognizable image, Van Dalen recalled. “The alternative spaces were like a laboratory. They really emboldened artists to make work that was free of any inhibitions.”

Anton van Dalen, pigeon inventory for the upcoming Frieze presentation of

The Pigeon Car (1987). Courtesy of P.P.O.W.

Hence, a pigeon coop sculpture shaped like a car. The car served as a symbol of opportunity for the young immigrant artist. Combining it with the kind of nature he was surrounded by in his youth was a way for Van Dalen to reconcile two drastically different life experiences.

From what I could see from my visit, Van Dalen’s pigeons seem to live very happy lives. The artist has a live video feed of the coop in his studio, and he releases them for an evening flight each day. New York City is a natural environment for them, he told me, because the city’s high rises mimic the English cliffs of their ancestral homes.

There are risks, of course, but they are mainly natural. Predatory hawks and falcons, or bad weather, which can disorient the birds and keep them from finding their way home—according to Van Dalen, the city’s wild flocks are actually “homeless,” descended from lost domesticated birds. “It’s still survival of the fittest,” he added.

Anton van Dalen, The Pigeon Car (1987), detail. Courtesy of P.P.O.W.

The pigeons’ care has been carefully considered for Frieze. The gallery provided me with a record for a clean bill of health written by a Brooklyn-based vet, who will be on call should anything go wrong during the show. The birds will stay overnight at the fair. The coop will be cleaned, and their food and water replenished, twice a day.

The birds will likely be unfazed by the bustling fair environment. “They are very used to people,” said Olsoff. “When you go visit him you can just walk into his pigeon coop.”

The view from the pigeon coop on Anton van Dalen’s roof. Courtesy of Sarah Cascone.

The Pigeon Car will be joined at P.P.O.W. by other works meant to hearken back to the New York City of the 1980s, a sort of recreation of an East Village street of the era, stocked with a large storefront painting by Martin Wong and silkscreens by Charlie Ahearn, among other works. “We always try to curate a show that will represent our program,” said Olsoff.

She’s also ready if PETA comes knocking: “We have packets ready in case people object to it.”

“I don’t want it to appear in any way as if I’m exploiting nature,” said Van Dalen. “I’m very lucky these pigeons have let me into their lives.”