Analysis

The Real Reason Sports Arenas Are Investing Millions in Contemporary Art Has Nothing to Do With Pleasing the Fans

This is not about game day.

This is not about game day.

Daniel Grant

The Chase Center in San Francisco, a top-of-the-line stadium that will become home to the Golden State Warriors basketball team when it opens in September, has all the customary amenities one associates with a contemporary sports arena: jumbotrons, 18,000-plus seats for fans, numerous dining options, 40-plus luxury boxes and suites… and scores of works of art. Art!

How and why did contemporary art get to be so intertwined with sports arenas?

The answer has very little to do with game days and much more to do with ringing money out of the spaces in the off season. Art suggests high-end. And a high-end vibe, these stadiums hope, will help them lure clients to rent out the venues for birthday parties, graduations, weddings, concerts, and corporate events.

The art on view is often high-end and unsubtle. Two of the 40 or so works in the Chase Center might also be familiar to regular visitors of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art: a 324-inch-long 1963 painted metal mobile by Alexander Calder, which will be sited at the Chase Center’s west entrance lobby, and a steel “Play Sculpture” by Isamu Noguchi (designed in 1975 and fabricated in 2017), which will be located on a nearby plaza. They are part of the museum’s permanent collection and have been placed on indefinite loan to the sports complex.

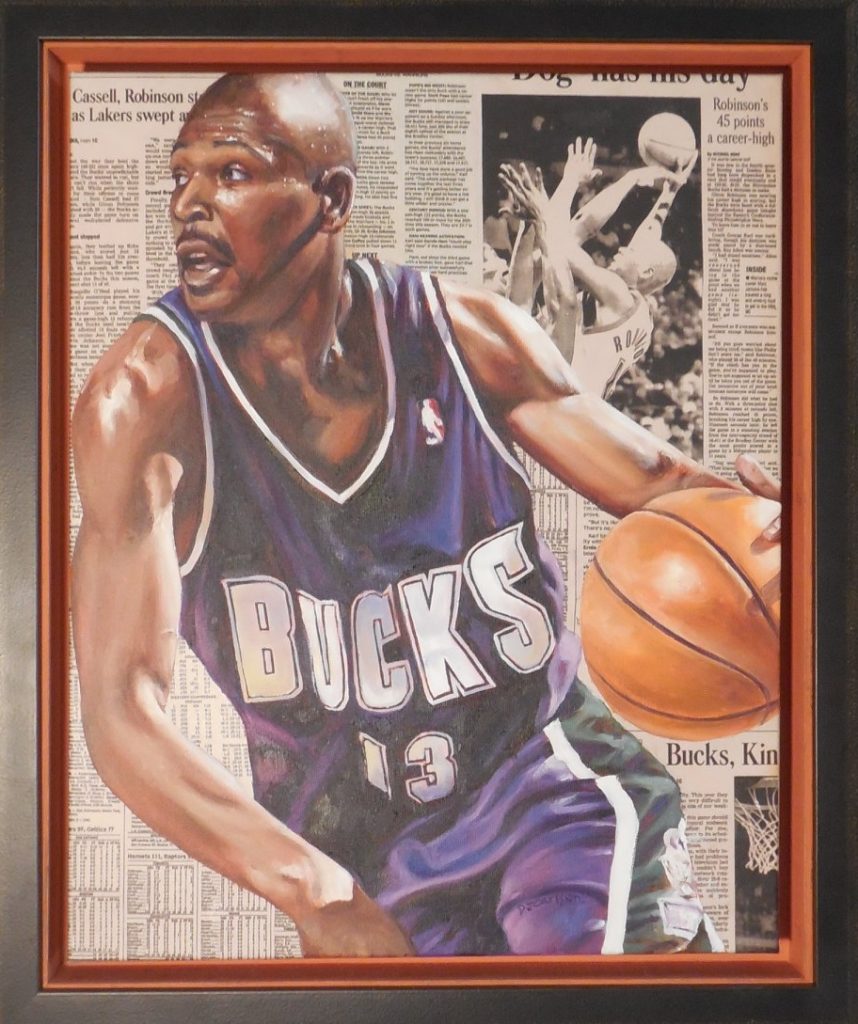

Derek Carlson’s Big Dog painting for the Milwaukee Bucks. Courtesy of the artist.

“Loan” is the museum’s way of describing it; “rental” is another, since the Chase Center is “providing SFMOMA with an honorarium” intended to “support exhibition and education programs at the museum.” A spokeswoman for the the museum declined to reveal the amount that the basketball team is paying SFMOMA, but noted that “the Warriors’ Chase Center is covering the costs of the commissions as well as potential future maintenance of the artworks commissioned and loaned by SFMOMA as needed.” In other words, both sides of the deal see it as a win-win—a rare scenario in a sports arena.

While some have bristled at the idea of a museum renting out its collection for profit, neither the American Alliance of Museums nor the Association of Art Museum Directors have any policies that would discourage this type of arrangement. “The more people who are able to see and enjoy art, the better,” said Douglas S. Jones, director of the Florida Museum of Natural History in Gainesville and former board chairman of the American Alliance of Museums. “The stereotypical sports fan may never darken the door of an art gallery or museum, so if they get to see art this way it’s great.”

Some—though not all—of the artworks that will be found at the Chase Center have a sports theme. Derek Carlson, a painter and public school art teacher in Wisconsin and one of the 33 artists whose works will be part of the Chase Center collection, regularly paints images of baseball players. “If people who come to a game are surprised to see art in a setting like this, that’s nice,” Carlson said.

David Huffman’s Double Jump [detail] will be in the Chase Center.

Notably, however, the art on view in these arenas is not really meant for game days—it was certainly not acquired to justify the high cost of tickets or to turn fans into season ticket-holders. Nor does its presence appear to lengthen the amount of time visitors stay in sports arenas. Many of the works often aren’t even sited on the main concourses.

Instead, the art is designed to make the space more attractive for rentals during other times of the year. Tracie Speca-Ventura, founder of the California-based Sports & the Arts, which acts as an art advisor and curator for sports franchises around the country, says that “sports arenas are not just for sports. These arenas are event centers.”

She notes that “for sports franchises, an art collection opens up marketing opportunities” and makes a facility that has only a limited number of home team games per year more attractive to high-end party planners. A spokesman for the Florida Marlins agrees that “art gives the ballpark more polish and definition.”

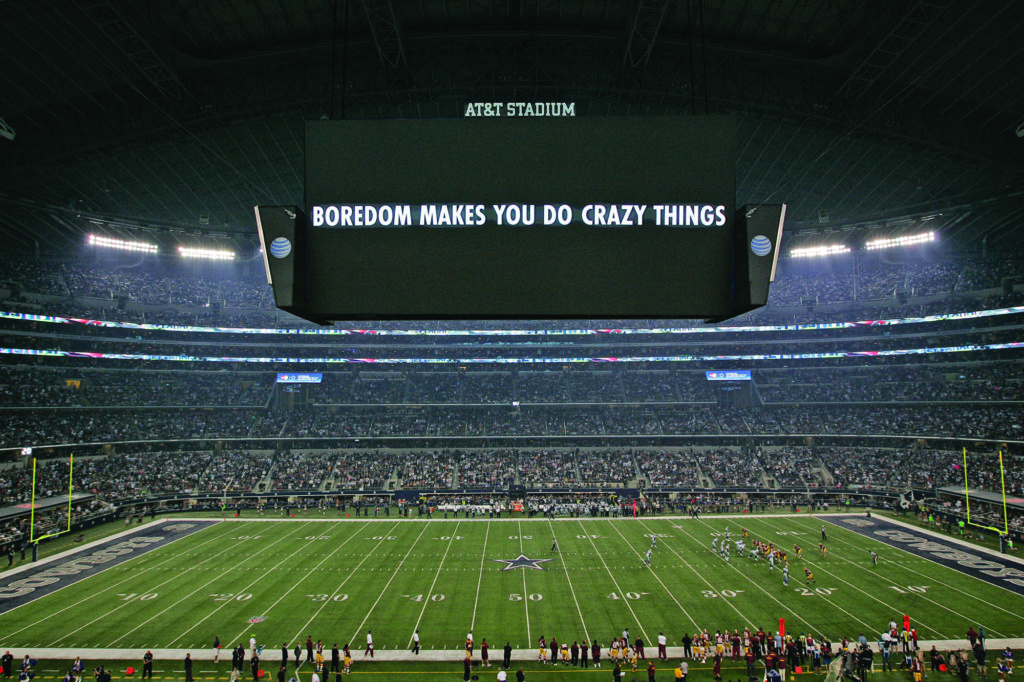

Jenny Holzer’s For Cowboys (2012) in Arlington, Texas. Photo by James D. Smith/Dallas Cowboys.

Sharron Hunt, director of the Kansas City Chiefs football team’s art program, notes that most of the artworks purchased for the recently renovated Arrowhead Stadium are sited on the club level, because that is where most of the events take place. (She also acknowledges that the people admitted there are less likely to be disorderly, causing any damage to the artworks.)

The significance of these collections, then, may extend well off he field, as sports venues begin to compete for conventions and party events with hotels, convention centers, and museums. Historic homes, art and natural history museums regularly promote themselves as ideal spots for weddings and other activities, trading on their collections and cultural cachet to woo event planners. The people who spend top dollar to hold elaborate events are accustomed to being in places where art is part of the experience, Speca-Ventura says. With the emergence of significant art collections at sports arenas, one sees for-profit enterprises jockeying for the same business with nonprofits, both using art as a sales tool.

Installation view of Franz Ackermann’s Coming Home and (Meet Me) At the Waterfall (2009). Courtesy of the Dallas Cowboys Art Collection.

The model for this trend is the $1.3 billion AT&T Stadium, where the Dallas Cowboys football team plays and which opened in 2009. The stadium contains 16 commissioned site-specific artworks, as well as 42 other works that are on view throughout the facility. Many of these works are by internationally known artists, such as Doug Aitken, Olafur Eliasson, Jenny Holzer, Anish Kapoor, and Lawrence Weiner. So far, the investment is paying off.

“We have something going on every day,” Phil Whitfield, whose title is art ambassador for the Dallas Cowboys, tells artnet News. “It could be a wedding or a rodeo, and you might have a wedding on the same day as a monster truck rally.”