Art Fairs

The ’80s Are Back, Baby! Art Basel Ushers a New Decade Into the Blue-Chip Pantheon

Basquiat may be leading the charge, but many of his peers are resurgent too.

Basquiat may be leading the charge, but many of his peers are resurgent too.

Julia Halperin

Has the 1980s generation muscled its big-shouldered way into the top tiers of the art market? At Art Basel this week, works no more than 35 years old are among the most expensive at the fair, and artists who were recently dismissed as overhyped or out of fashion—like Julian Schnabel and Peter Halley—are being shown proudly and prominently. “The ‘80s are back big time,” says the art advisor Wendy Cromwell.

Notably, many of the priciest works in Basel are from the decade of spandex and Madonna, including a $35 million painting by Jean-Michel Basquiat at Lévy Gorvy (1982), a $25 million Francis Bacon at Marlborough Gallery (1982), a $12 million painting of a gun by Andy Warhol at Mnuchin Gallery (1981-82), and a Sigmar Polke at David Zwirner Gallery priced at nearly $9 million that sold during the VIP preview (1989).

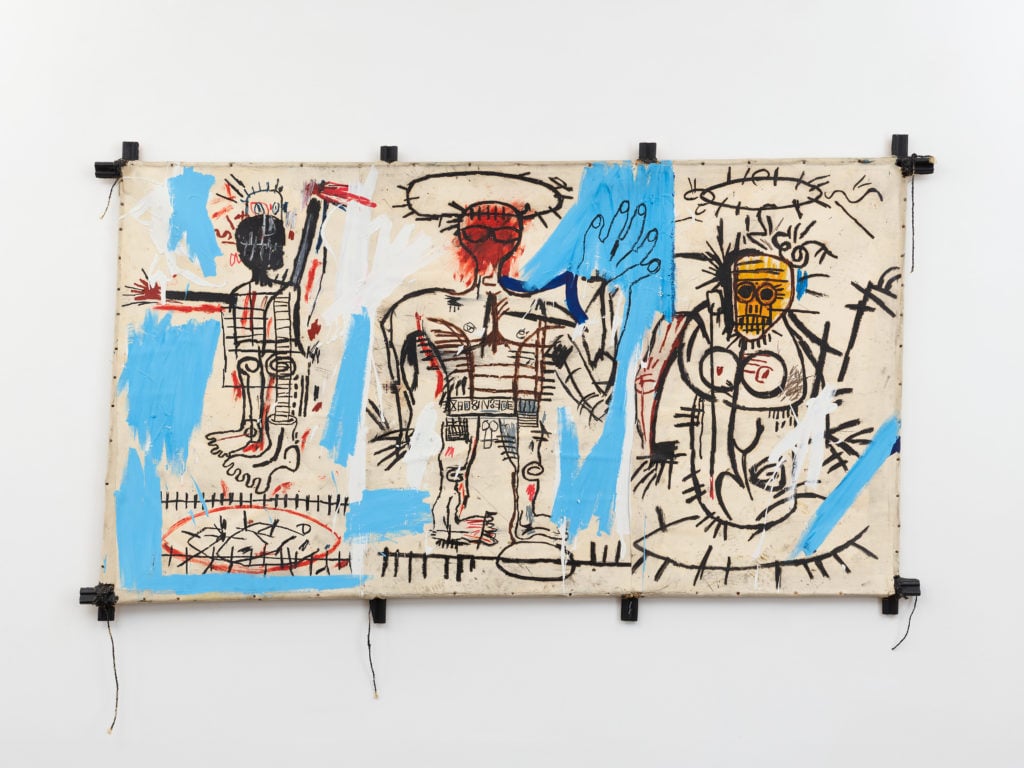

Basquiat’s Baby Boom (1982). © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, ADAGP, Paris and ARS, New York.

Experts say the increasing visibility—and price points—of work from this decade is the result of a variety of factors: decreasing supply for more desirable early work by artists associated with the 1960s, a growing recognition of the ‘80s as a tipping point in certain artists’ careers, and the market’s tireless quest to recover undervalued art historical figures.

The fact that the fair comes just one month after Basquiat unseated Warhol as the most expensive American artist ever to sell at auction has also not gone unnoticed. (As the newsletter In Other Words points out, Basquiat is one of a number of ’80s artists whose work performed well in New York’s spring sales, although his market operates in a different stratosphere.)

A Wider Return

“Internationally, there’s been a rediscovery of bodies of work from the ‘80s by American, European, and Asian artists, especially Japan and Korea,” says Nick Buckley Wood of Thaddeus Ropac Gallery, which sold an untitled painting from 1983 by Polke priced at $4 million and is also showing a large 1984 canvas by the Italian painter Emilio Vendova, a pioneer of Art Informel, priced at $425,000.

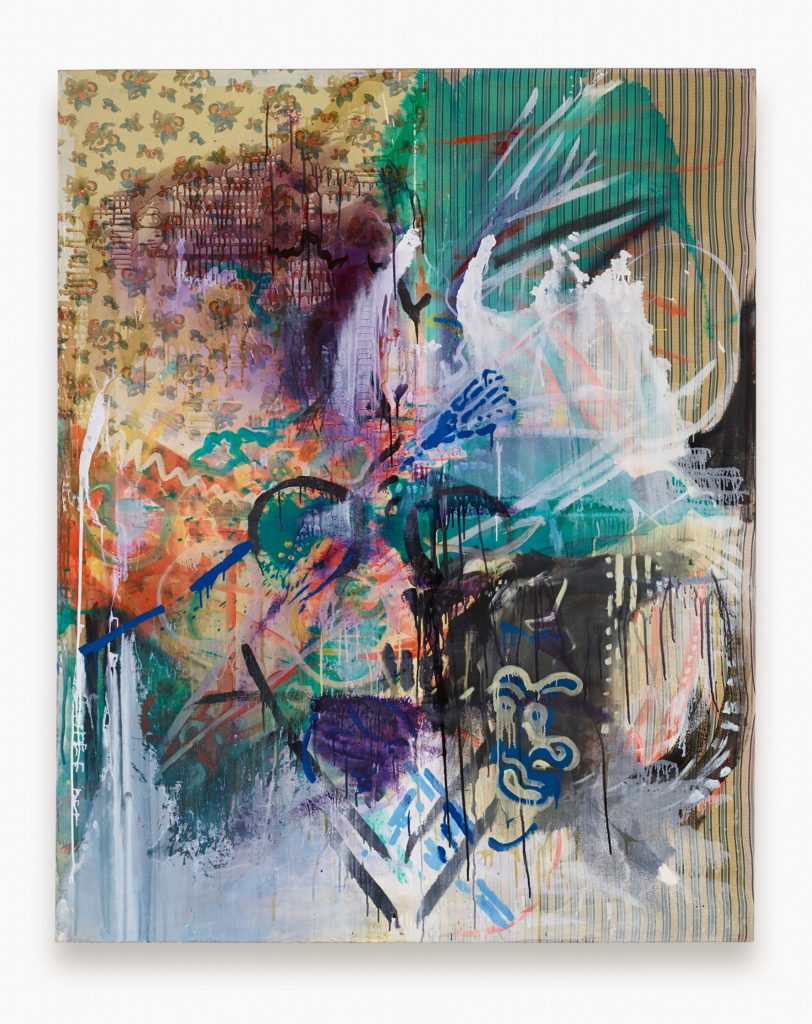

Sigmar Polke’s Untitled (1983). Image courtesy of Galerie Thaddeus Ropac. © The Estate of Sigmar Polke, Cologne / ADAGP, Paris, 2017.

With the benefit of 30 years’ hindsight, certain ‘80s artists “have become canonical by now,” says Philomene Magers of Sprüth Magers, which sold a 1986 sculpture by Peter Fischli / David Weiss priced at €420,000. “Beyond that, they are dealing with questions that feel vital today.”

Artists closely associated with the ‘80s—particularly those who overheated during that decade’s art market boom—are also being re-examined by institutions. Earlier this year, the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York presented “Fast Forward: Painting From the 1980s,” which presented stars of the era alongside lesser-known names.

“I liked the challenge that this has been perceived post-‘90s as outmoded, and seeing what it would feel like to bring it back out,” says the show’s curator Jane Panetta. As contemporary painters rework pop imagery and double down on figuration—techniques at the heart of ‘80s painting—“it ended up feeling even more resonant and connected to the present than I expected.”

Julian Schnabel’s Untitled (2015) at Blum & Poe. Image courtesy of Blum & Poe.

Meanwhile, Julian Schnabel—perhaps the epitome of ‘80s art-world excess—has a major solo show in the works at the Legion of Honor in San Francisco next March, as well as a recent show at the Aspen Art Museum; he is also currently filming his latest feature film, a biopic of Vincent van Gogh. A 2016 painting by Schnabel is on view at Blum & Poe, priced at $325,000.

Other Explanations

Not so long ago, ‘80s material was regarded as a stale trend whose time had passed. Kadel Willborn of Moritz Willborn Gallery, who sold several photographs by the pioneering conceptual photographer Barbara Kasten during the fair’s VIP preview ($15,000–50,000), says that when he showed the same series in 2010 at Frieze, “you could tell it was too early—the ‘80s were still a no-go.”

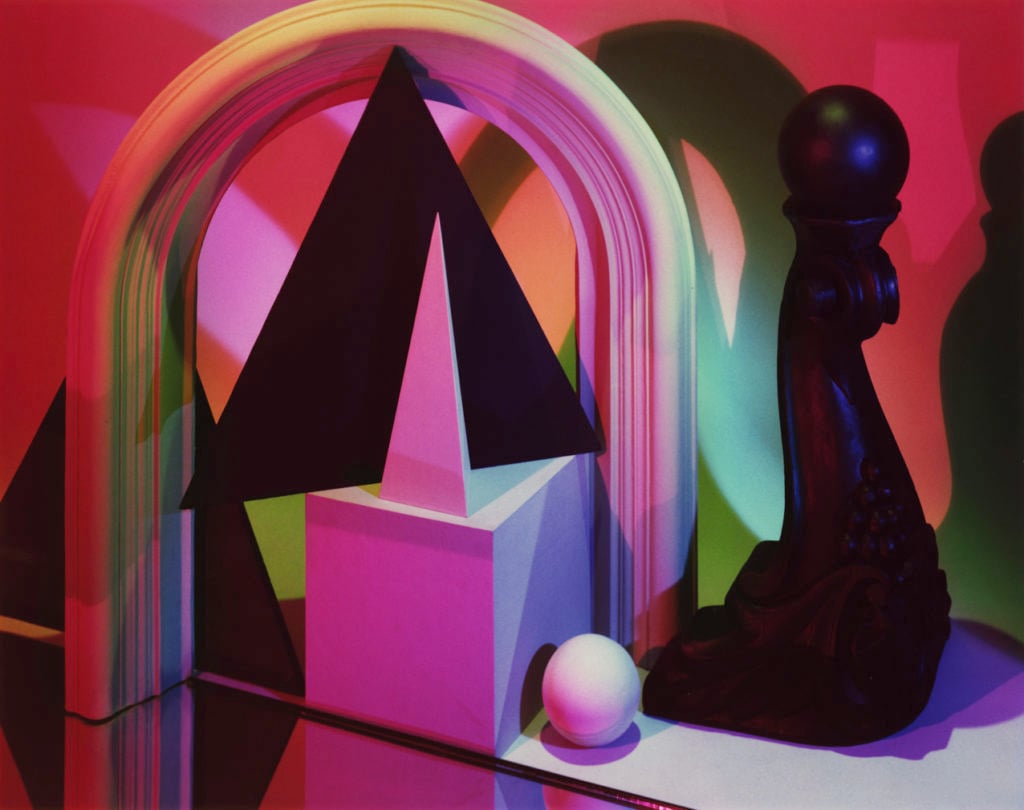

Barbara Kasten’s Construct NYC (1984). Image courtesy of Galerie Kadel Willborn.

But now, “people looking at Schnabel are the same collectors who are looking at Polke and thinking, ‘The former is $400,000 and the latter is $4 million—maybe I should think about Schnabel,’” Cromwell says. Furthermore, the work is being considered by a younger generation of collectors who don’t have the same preconceived notions about ‘80s art as the ones who had the opportunity to buy it the first time around.

Still, others maintain that the presence of ‘80s work at Art Basel is merely a ripple effect of other market trends. “It’s not that I’m seeing more ‘80s work than normal, but it’s standing out because what I am seeing is less of the ‘60s stalwarts and high-end blue-chip, like Richter and Koons,” says the art advisor Todd Levin, the director of the Levin Art Group.

Sales of those pictures, he says, are “taking place on the private market, away from auctions and art fairs.” In a gun-shy market, “people are a little cagier—they don’t want their stuff out in public as much, they’re fearful of it getting burned.”

Sales Galore

Whatever their motivation, dealers have found willing buyers for ‘80s material. Metro Pictures sold the first work from Cindy Sherman’s fashion series, from 1983, priced at $1.5 million, as well as two drawings by Robert Longo from the early 1980s at prices ranging from $400,000-550,000, during the VIP preview.

Cindy Sherman’s Untitled #122 (1983). Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

Meanwhile, Greene Naftali sold a suite of six monochromes on lead from 1989 (priced at €950,000) by the German artist Günther Förg, who will have a major retrospective at the Dallas Museum of Art in 2018. Galerie Bärbel Grässlin sold Ohne Titel (1989) by the German painter Albert Oehlen, priced at more than $1 million. (For comparison, a much larger work by Oehlen from 2016 was still available on Wednesday across the aisle at Galerie Max Hetzler, priced at €625,000.)

Many note that increased interest in material from 30 years ago is “part of a general look to the past over the last five years,” as the dealer Tim Blum put it. Work that is slightly more historic—and in finite supply—is considered a safer bet than art by younger names.

But even some rediscoveries have experienced rapid price increases often associated with young guns. Blum & Poe sold Untitled 80-9-C (1980) by the Korean artist Chung Sang-hwa, who was active in the ‘80s and ‘90s but little-known internationally until recently, for $425,000. The gallery sold the same work in 2015 for $90,000.

Value of Hindsight

Despite the increased attention, there are still “pockets of the ‘80s that have yet to be mined,” Cromwell says. Abstract painters from the period, for example, such as A.R. Penck and Harvey Quaytman, are only now beginning to be more fully examined. (Quaytman has a solo booth at Van Doren Waxter at the fair and a retrospective at the Berkeley Art Museum planned for 2018.)

George Condo’s Without a Cause (1986) at Sprüth Magers. Photo courtesy of the gallery.

“I think it is not a matter of reevaluation but more of a rediscovery for a new and broadened audience,” says Max Hollein, the director of the Fine Art Museums of San Francisco, who is overseeing the Schnabel show and who organized an exhibition of Peter Saul’s work currently on view at the Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt.

“The interesting perception for some of the art that was produced in the 1980s right now is that it is on the one hand—after about 35 years—a generation old and already historic,” he continues, “and on the other hand still has a very contemporary edge and is certainly not history yet, but very much attuned to the present.”