Art Demystified is a series that attempts to shed light on esoteric aspects of the art world.

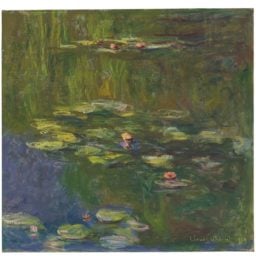

Commissions are an important source of income for auction houses. Courtesy of Spencer Platt/Getty Images.

The pricing of art sold at auction can often be deceiving for first-time buyers, who may end up paying more than they expected after the hammer falls.

In addition to the winning bid for a lot at auction, known as the hammer price, auction houses charge buyers an additional fee known as a buyer’s premium, which is calculated as a percentage of the hammer price. The modern buyer’s premium was introduced in 1975 by Sotheby’s and Christie’s; the two houses charged 10 percent then. Today, the houses charge buyers premiums of up to 30 percent.

Auction houses already charge a seller’s commission, a fee paid by the consignor to the auction house which goes towards the research, valuation, and promotion of an artwork. So how can an auction house justify also taking a cut from the buyer?

Christie’s auctioneer Jussi Pylkkanen. Courtesy of Carl Court/Getty Images.

“I think this [buyer’s premium] equates to a level of trust and research executed by the auction house to warrant being paid the premium,” Jason Rulnick, specialist of post-war and contemporary art at artnet Auctions, explained. “We are doing an important service for a collector, they should feel happy to pay something for us making a transparent marketplace and inspecting art and giving an accurate condition report.”

Buyer’s premiums also raise questions over the accuracy in which auction houses report sales statistics. While the estimates do not include buyer’s premiums, the sales prices announced by auction houses do include the mark-ups. In other words, artworks that don’t reach the low estimate can suddenly look as if they did simply by adding the buyer’s premium.

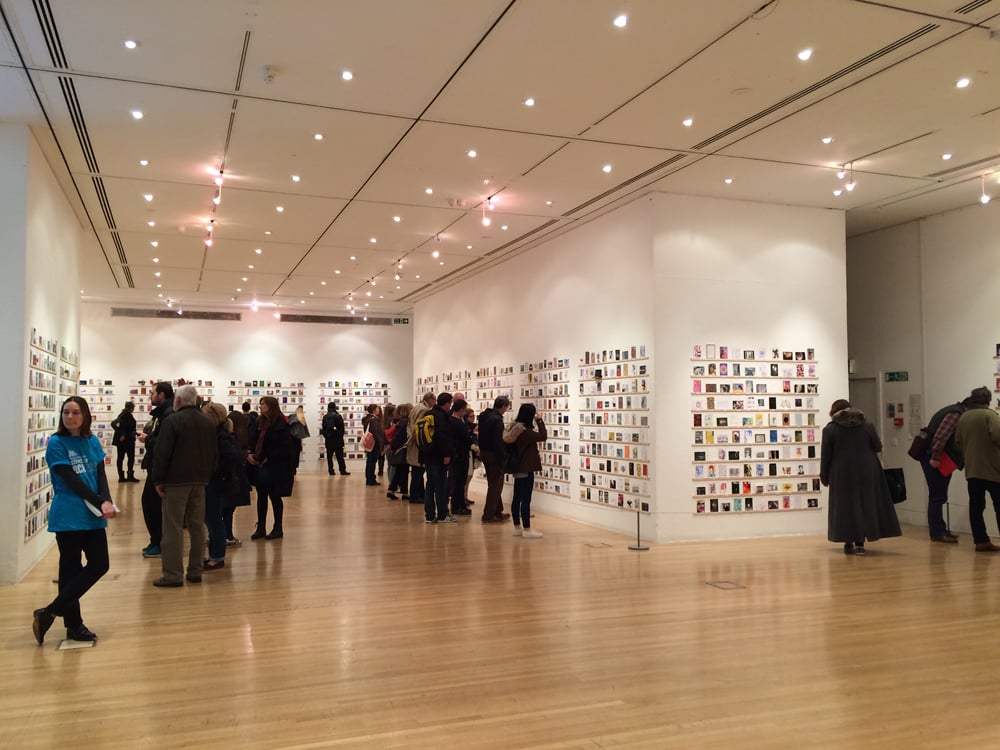

“RCA Secret” Auction. Courtesy of Aine Duffy.

“Often, a user will research a price in the database, and then believe that they as a private seller are entitled to the same amount of money for their work,” Rulnick said. “Sellers are always disappointed when you try to explain that from the premium price nearly 30 percent never gets passed to the owner, because the house will take say 20—25 percent on average and there’s often a sellers commission of say 5—10 percent.”

Despite these issues, Rulnick believes that the auction market remains one of the most transparent platforms for buying and selling art. “The buyer knows in advance what the premium is, the seller too knows what premium is taken from the buyer,” he said. “And the sale result price is always marked as hammer only, or including premium.”