Analysis

Beyond Context Collapse: 4 Things Fairs Can Do to Differentiate Themselves—and Strengthen the Art World in the Process

Art fairs dominate the art world, but they can make many improvements to help themselves and galleries survive.

Art fairs dominate the art world, but they can make many improvements to help themselves and galleries survive.

Elizabeth Dee

Context collapse is threatening big art fairs. As I discussed in the first part of this series, context collapse happens when fairs grow too large, and too quickly, to foster as many meaningful encounters with art as they could at a smaller scale. But we cannot dismiss fairs—large or small—as passé or of little relevance. They remain essential to the survival of the private market, where artists are paid for their work and galleries have the potential to grow. So the question becomes: what is working for fairs, and how can we improve them?

In recent years, successful large fairs have begun to market themselves by publicizing benchmark sales, frequently of works priced above $1 million. These sales largely benefit internationally established artists and galleries that do more than $50 million in business per year.

There is value in this approach: If fairs did not promote the top end of the trade, auction houses might become the only platform for this echelon. With the help of fairs, galleries have been able to reframe the market at its highest end. But this isn’t enough. The focus on the top has deepened the class system at these fairs, and the benefits are disproportionately felt.

In other words, context collapse has created a gap between a fair’s perceived “halo effect” and its true “network effect.” Fairs are doing their job when they assemble collectors that galleries want to do business with, who in turn are more likely to do business with galleries at the fair that are new to their network. But without significant orientation to the unknown, established collectors will gravitate toward what they already know well.

Sunday Painter, Focus, Frieze London 2018. Photo: Linda Nylind.

By refining their strategy, however, fairs can strengthen their network effect, especially if they are fighting for the right market. We know the majority of galleries at fairs need a strong context and support, far more than the few that show well-established artists. So fairs should foster the context that is required to redefine and develop markets that have not yet come into their own.

Context-rich fairs are incredibly important right now—they provide a needed platform to introduce and encounter new artists and to foster a culture of research-based collecting. Fairs that have remained true to a content-driven vision or a core mission often perform well for their participating galleries and for themselves. How do these fairs succeed in avoiding context collapse—and how can other fairs learn from them? Here are four lessons.

US colleges require students to declare a major. Each art fair should choose one as well. Like galleries, fairs cannot be everything to everyone—and they need to differentiate themselves to avoid looking and feeling the same. And like galleries, fairs should zero in on what they can offer that the competition does not. In the process, they have a chance to define what kind of collector they want to cultivate and what kind of experience they want to create for that particular audience.

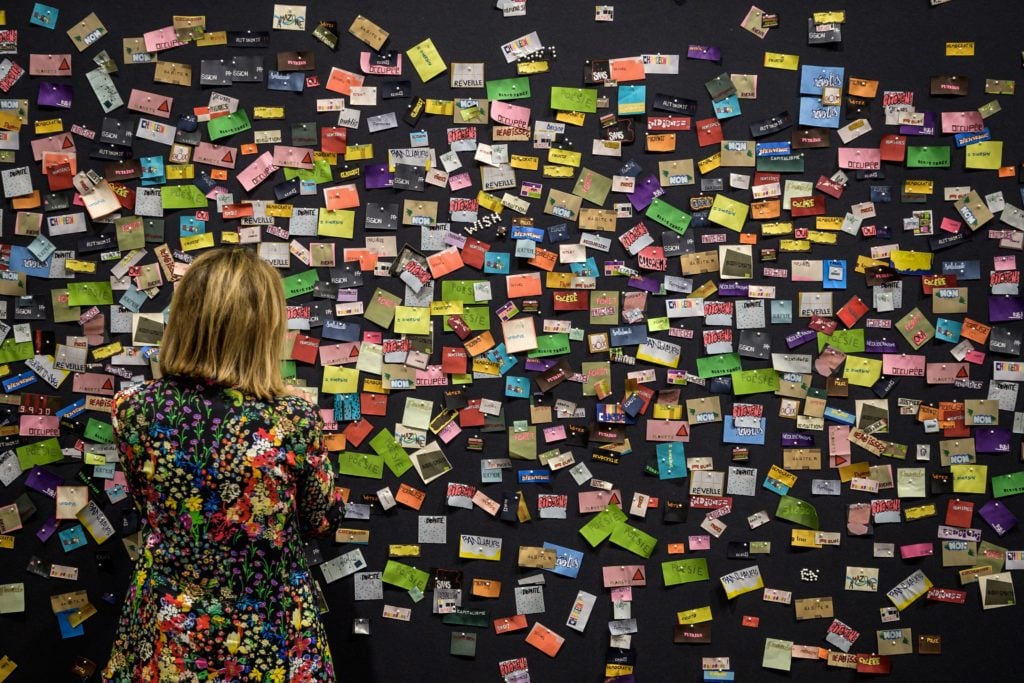

Rivane Neuenschwander’s Bataille at VIP opening of Art Basel 2019. Photo: FABRICE COFFRINI/AFP/Getty Images.

Today, many fairs have lost direction. Instead of being a “place to be,” they have become a “place I cannot afford not to be.” This is not entirely surprising during a time of big transitions in several key industries and economies. But by refining their focus, fairs will be better able to combat redundancy by fostering direct connections between collectors and galleries—which should be the goal—rather than simply between collectors and fairs.

Right now, fairs often present strong branding, not a strong sense of mission. But having a strong brand is no substitute for having a strong why. To remain relevant, fairs should consider limiting their mission to a few objectives. For fairs, as for other businesses, pivoting, consolidating, and collaborating are not signs of weakness, but signs of strength. A narrowing of focus and an enrichment of context can create a memorable experience for both collectors and galleries.

Fairs make a decision to align with one of three elements: people, experience, or sales information (and the power that comes with accruing that information). I would argue that most fairs have aligned with the latter—at the potential expense of people, experience, and perception.

Alexandra Pirici’s Aggregate (2019). Courtesy of the artist and Art Basel.

When fairs choose to highlight individual transactions by sending pages and pages of sales results (which, of course, the press asks for and amplifies), rather than promoting newly commissioned artworks or the inherent value of historical material, the big picture gets lost.

Additionally, this entirely removes the wider art community from the picture; it alienates collectors (who value an art experience over a shopping experience) and curators (who don’t participate in the market in the same way) from the message.

What makes big fairs succeed is not just sales, but the fact that they serve as gathering places for a global network. As such, fairs have the potential to prioritize experience by creating an environment that encourages authentic discoveries and, in the process, actually expanding the market.

The entrance to the Park Avenue Armory, TEFAF Spring 2018. Photo: Kirsten Chilstrom.

One example of a fair that has thrived by privileging experience is the European Fine Art Fair (TEFAF), which produces three fairs, including two in New York, which focus on museum-caliber art from the ancient to the Modern eras. With fewer than 100 galleries per fair in New York, TEFAF’s modest scale allows it to focus on the overall experience rather than compete with larger fairs on blockbuster sales. This prioritizes a community of buyers and galleries over the brand or market. TEFAF’s distinct agenda in New York revolves around a communal experience as much as a cultural one. Unfortunately, TEFAF does not specialize in developing artists and galleries, where such a model could make a significant impact.

Large fairs have arguably been expanding beyond what the market will bear by selling more space to exhibitors who don’t actually need more space—and, in the process, sidelining galleries that can’t afford a larger footprint. In addition, some fairs are increasingly offering “curated” or editorial sections—ostensibly thematic groupings with guest curators, or press-worthy sectors devoted to emerging artists, galleries, or rediscoveries—for galleries whose fair budgets do not match those of the more established dealers. This agenda puts even greater pressure on galleries to pay to participate, and further drives economic inequality at these events.

Among the more problematic sectors are thematic projects inside the fair and outdoor sculpture sections outside of it. Dividing viewers’ attention is not a selling point for galleries (though fairs could use these sections to more creative possibilities if they secured sponsorships to allow galleries to participate for free). As it stands, however, these sections tend to contribute to context collapse and create additional financial burdens for galleries, which have to underwrite their participation in order to gain visibility (and stave off invisibility). And as some of these sections approach the scale of international biennials, galleries have to commission and produce new artworks and rent additional space beyond their primary stands to accommodate them with no promise that they will find a home after the fair is over.

Visitors at Art Basel in Hong Kong are already familiar with VR and AR technologies. Photo: Theodore Kaye/Getty Images.

One fair this past season had no less than eight themed sections devoted to underserved markets. As an attempt to sell space, avert context collapse, or both, such practices are problematic. They may actively reinforce bias in areas of the art world that should be framed as coexisting and equal, including, but not limited to, emerging or developing markets. Big fairs may say they are creating platforms for these emerging and developing markets through the special sections, but I would argue that they do so largely to serve a primary purpose—selling real estate at only slightly discounted prices for far less visibility—and galleries rarely come out ahead.

More manageably scaled fairs that have a singular mission have avoided a surfeit of themed and traditional “curated” sections. We do not hear these kinds of complaints at Independent, the fair I co-founded. I also do not see this as a problem at Frieze Los Angeles, FOG, the Dallas Art Fair, MECA, NADA Miami, Felix, Frieze Masters, Paris Internationale, or TEFAF. That is why I am convinced by that limiting scale and focusing the experience of collectors around the content lies at the heart of the solution.

The biggest problem facing art fairs today is a problem of scale—going big without innovation or collaboration with galleries. Independent avoids context collapse in large part by each year bringing forward what is unique about a spectrum of exhibitors that define the fair, reflecting the actual art ecosystem, and possibly pointing to the future.

Since 25 percent of art collectors worldwide have a home in New York, there is a great built-in audience, but also a chance to define a specialty. At Independent, we cannot be everything to everyone. We don’t aspire to reflect the market’s top end, but we do succeed in making the fair a place to be for collectors, and accelerating markets for both new and historical art.

Independent is fostered by participating galleries who largely believe that profit is a byproduct of the art community’s vibrant culture. The fair aims to offer a picture of the different, overlapping contexts in which artists and galleries operate. We were among the first, for example, to present work by outsider artists on equal footing with and alongside formally trained artists. Our strength lies in considering how shifting the accepted context of these presentations might change the way collectors and decision-makers view the work.

People watching Jon Rafman’s video at Sprüth Magers © Art Basel, 2018.

This is not the only route. Fairs that place a premium on promoting sales have unique opportunities of their own. They could build a tighter network for the highest performing galleries, currently seen only as competitors, and leverage this sector’s market dominance beyond one or two global events and throughout the course of the year. These fairs already assemble well established galleries (who do not otherwise collaborate), suggesting that they could develop further platforms and create alliances that expand exhibitors’ influence and can compete with the auction houses, helping to shield against the forces of competition that do not serve their artists or estates.

Solutions have to be bold and involve big changes that reflect the art world we want to inhabit in the future. Fairs can be powerful territory for change, and fair leadership must take responsibility for the way they can change the ecosystem for the better—for galleries, for collectors, and ultimately, for artists.