Galleries

Art Law On Authenticity and Provenance When Buying and Selling Art

What are the issues of authenticity and provenance when it comes to buying and selling art?

What are the issues of authenticity and provenance when it comes to buying and selling art?

Ronald D. Spencer

This essay is about a legal doctrine—mutual mistake of fact, which allows a contracting party to rescind a contract and thereby be returned to the pre-contract position. For a sale of art, rescission (for example, after the sale, the art was discovered to be fake) would result in the purchase price going back to the buyer and the seller taking back the art. The courts have had difficulty dealing with this doctrine, in part, because the consequence of its application (contract rescission) is so drastic for one of the contracting parties.

● ● ●

As Between a Buyer and Seller, Who Bears the Risk of Mistake?

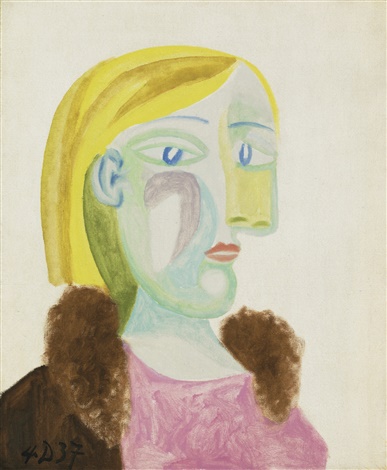

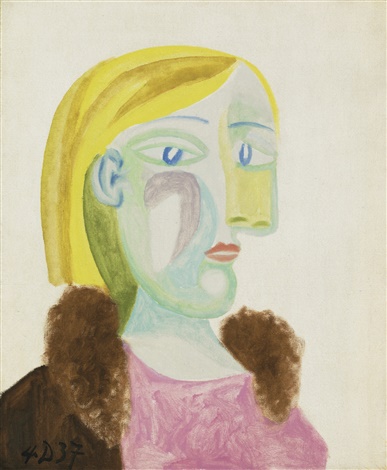

Puzzle: An art collector sells another collector a drawing which they both believe was created by Picasso. After the sale, facts came to light which make it clear that the drawing is a fake. Both buyer and seller were mistaken as to the authorship of the drawing and the buyer wants his money back. Will a court rescind the sale on grounds of their mutual mistake?

Answer: See below

The law of mutual mistake of fact, resulting in rescission of the agreement (usually a sale agreement), has had a long history of hard-to-reconcile court decisions. And, at least in New York, two decisions in the early 1990s involving the authenticity of art only increased the confusion.

The doctrine of mutual mistake of fact applies where the parties to a contract have reached an agreement which does not allocate the risk of a fact or circumstance of which both parties were unaware at the time of contracting. A contract entered into under a mutual mistake of fact is subject to recession, that is, upon demand of one of the contracting parties, the contract is ended or reversed and the parties are thereby returned to their pre-contract positions. The “mutual mistake” must exist at the time of contracting and must be substantial. Thus, post-agreement, a fact comes to light that neither party anticipated or even thought about. (Seller and buyer thought they were dealing only with a cornfield but, post-sale, oil is discovered under the field.) A party alleging mutual mistake must come forward with a “high order of evidence” to overcome the presumption that the contract (sale of a cornfield) evidenced the intent of the parties.1 It should be noted, however, a number of cases incorrectly analyze mutual mistake doctrine in terms of contract formation, (‘meeting of the minds’) as opposed to contract interpretation in the following kinds of language:

… a contract entered into under a mutual mistake of fact is voidable and subject to rescission.

… The mutual mistake must exist at the time the contract is entered into and must be substantial. The idea is that the agreement as expressed, in some material respect, does not represent the “meeting of the minds” of the parties.2

But a “meeting of the minds” quite clearly formed the contract in question. The real issue for mutual mistake analysis is how the contract allocates the risk of the mistaken or unknown fact between the parties.

Naturally enough, “a party bears the risk of a mistake when the risk is allocated to him by agreement of the parties.”3 Therefore, there can be no rescission on the ground of mutual mistake when the contract itself (or circumstances at the time of contracting) indicates the parties acknowledged and allocated the risk. And several courts have held that where the parties to a contract identified or allocated a risk, there was no basis for rescission on the ground of mutual mistake.4

In determining whether rescission is warranted in a given circumstance ‘there must be excluded from consideration mistakes as to matters which the contracting parties had in mind as possibilities and as to the existence of which they took the risk.5

… the parties contemplated the possibility that the representations and warranties may not be completely accurate. … In doing so … [one party] contractually agreed to assume risks associated with the possibility that the seller’s representations and warranties were erroneous. Thus, [that party]… waived its right to now claim mutual mistake.6

Great Difficulty for Courts in Formulating Rules for Mutual Mistake Cases

Farnsworth, (Farnsworth on Contracts7) notes that “courts have had great difficulty in formulating rules for mutual mistake cases …” We can see this in two contradictory decisions described below.

A landmark case on mutual mistake arose from of a contract for the sale of a cow, “Rose 2d of Aberlone.” Both seller and buyer believed that Rose was barren and so the price was fixed at $80, about one-tenth of what Rose would otherwise have been worth. When the seller discovered that Rose was with calf, he attempted to rescind the contract and refused to deliver Rose to the buyer. The Supreme Court of Michigan held that the seller was entitled to rescind if “the cow was sold, or contracted to be sold, upon the understanding of both parties that she was barren, and useless for the purpose of breeding, and that in fact she was not barren, but capable of breeding.8

But, in another classic court decision,9 a bull calf sold as a breeding bull was, upon maturity, found to be sterile. The seller had warranted only that “[a]ll animals are believed to be straight and right.” The court held that there was no mutual mistake of fact because “where the parties know that there is doubt in regard to a certain matter and contract on that assumption, the contract is not rendered voidable because one is disappointed in the hope that the facts accord with his wishes. The risk of the existence of the doubtful fact is then assumed as one of the elements of the bargain.”10

Mutual Mistake in the Art World

Legal disputes in the art world often involve a claim that buyer and seller were mutually mistaken in believing in the art’s authenticity, and therefore their contract of sale should be rescinded—the art returned to the seller and the purchase price to the buyer. At the time that they entered into the contract, both parties shared the same erroneous belief. The obvious and drastic real-world result of court-ordered contract rescission is that the buyer gets his money back and the seller is left with a problematic piece, while a court’s refusal to rescind leaves the buyer stuck with the piece.

Not surprising, then, that courts are often reluctant to order a contract rescinded based on a doctrine of mutual mistake and have developed a number of rules which limit the right of one party to reverse the bargain. A recent federal court decision in New York, ACA Galleries, discussed below, has applied some of these limitations to the doctrine of mutual mistake and got it quite right.

But before this essay addresses ACA Galleries, it is useful to examine why mutual mistake of fact claims are made, when, in most art sales, a warranty of the seller allocates the risk of forgery or mistaken attribution.

Why Make a Mutual-Mistake-of-Fact Claim in the Age of Warranties, Express and Implied?

Most sales of art involve contractual promises (warranties) by the art merchant seller that the art has been created by the named artist. Even if (as is often the case) the contract or invoice is silent, warranties are implied (i.e., incorporated into the sale terms) by operation of state law.

Uniform Commercial Code Section 2-313 provides that “[a]ny description of goods which is made part of the basis of the bargain creates an express warranty that the goods shall conform to the description.” A representation that a work is by a named artist should trigger this warranty. In sales by art merchants, Uniform Commercial Code Section 2-314 provides that a “warranty of merchantability” is implied in any contract of sale (unless it is explicitly waived or modified), which requires that the goods “must be at least such as … pass without objection in the trade under the contract description.”

In addition, under New York’s Arts and Cultural Affairs Law, an art merchant’s provision of “a certificate of authenticity or any similar written instrument” to a non-dealer collector will be deemed an express warranty of authorship (and not just the seller’s opinion).11 This warranty of authenticity will be deemed breached by the seller unless he had a reasonable basis in fact for his warranty.12 Thus, if the seller might be able to show he had a reasonable basis in fact for his warranty of authenticity, but the buyer, nevertheless, believes the piece is not authentic, the buyer might make the alternative claim of mutual mistake of fact, if that is the buyer’s only viable claim, other than fraud (a notoriously difficult claim to prove). Warranties also do not provide a remedy for seller’s remorse, when a seller wants to rescind because the parties incorrectly believed the work was by an unimportant artist.

Another reason for a disappointed buyer to bring a mutual mistake of fact claim, is that, under the Uniform Commercial Code, the statute of limitations for a warranty claim is four years from the sale. A buyer wishing to bring a warranty claim more than four years after his purchase will need to find another legal theory for his claim. Thus, art buyers almost always include a contract rescission claim against their merchant-seller based on mutual mistake of fact—such a claim being a contract claim, with a six-year statute of limitations in New York. At least in New York, the buyer will have another two years to bring his claim.13

ACA Galleries Case Gets It Right

In ACA Galleries v. Kinney, ACA sued Kinney for selling it a forged Milton Avery painting—demanding rescission of the sale and return of its purchase price under the doctrine of mutual mistake.14 ACA had inspected the painting, determined it was a work by Milton Avery, and agreed on a purchase price of $200,000, which was duly paid based on a bill of sale describing the painting as “Milton Avery Oil on Canvas.” Soon after the sale, ACA had the painting examined by the Milton & Sally Avery Arts Foundation, which determined that the painting was not authentic—whereupon ACA demanded, and was refused, the return of its purchase price.

Judge Cedarbaum described the limitations on the doctrine of mutual mistake as follows:

. . . the doctrine of mutual mistake “may not be invoked by a party to avoid the consequences of its own negligence.” … Mutual mistake is further limited if the party wishing to invoke the doctrine bears the risk of the mistake because he was aware of his limited knowledge but acted anyway. Under §154 of the Restatement (Second) of Contracts, a party bears the risk of a mistake when “he is aware, at the time the contract is made, that he has only limited knowledge with respect to the facts to which the mistake relates but treats his limited knowledge as sufficient.” … “Contract avoidance on the grounds of mutual mistake is not permitted just because one party is disappointed in the hope that the facts accord with his wishes.” . . . In such situations, it is sometimes said that in a sense there is no mistake at all, but rather “conscious ignorance.” Restatement (Second) of Contracts §154 (1981). . . .

Courts have found that the failure to investigate constitutes negligence15 sufficient to bar the application of the mutual mistake doctrine. For example, … the First Department denied rescission based on mutual mistake where the corporate seller of a residential cooperative unit failed to investigate its own property before sale and thus failed to discover that the unit had been unoccupied, which made it more valuable. … The uniqueness of the subject of the transactions is considered when assessing the risk a party bears. For example, when a civil engineering company turned out not to have the earning potential that it had been presumed to have before the defendant agreed to purchase it, the Second Circuit found no mutual mistake. … The court reasoned that a civil engineering business is “personalized, highly technical, and extremely risky” and that “neither party could safely assume that the projected earnings would be realized.”

It is undisputed that Kinney gave ACA access to the painting at a New York City storage facility before the purchase. It is also undisputed that [ACA] inspected the painting and believed it to be authentic, but ACA waited until after the purchase to have the painting examined by the Avery Foundation. ACA’s failure to take advantage of its opportunity to consult the Avery Foundation before buying the painting precludes it from claiming mutual mistake.16

On appeal, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed Judge Cedarbaum’s judgment in the following language:

It is uncontested that ACA made out a prima facie case of mutual mistake under New York law. However, ACA cannot obtain rescission because of its failure to investigate the authenticity of the painting at issue. Although Kinney ensured the availability of the Milton & Sally Avery Arts Foundation to inspect and authenticate the painting prior to its sale, ACA instead elected to ask the Foundation to inspect the painting following its purchase. ACA was aware that its self-conducted pre-purchase inspection provided it with “only limited knowledge with respect to the facts to which the mistake relates but treat[ed its] limited knowledge as sufficient.” Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 154(b). Moreover, ACA was aware that an authentication by the Foundation “would make the painting more saleable at a higher price.” . . . ACA could have accepted the higher price that accompanies certainty of authenticity, but chose instead to accept the risk that the painting was a forgery. The contract is not voidable merely because the consciously accepted risk came to pass.17

Interestingly, ACA did not assert a breach of the warranty under U.C.C. 2-313, which might have been successful.

The Feigen Decision Gets It Wrong

13 years before Judge Cedarbaum’s decision in ACA Galleries, a New York court applied the law of mutual mistake of fact to issues of authenticity of visual art, and reached a result that seems inconsistent with both the law of mutual mistake and with art world practice (but which was unanimously affirmed on appeal).

In 1989, the art dealer Richard Feigen purchased a drawing signed “H. Matisse ‘47” for $100,000 from Frank Weil, a collector (not a dealer), and soon after sold the drawing for $165,000. In early 1990, the buyer brought the drawing to Acquavella Gallery, which wrote the administrator of the Matisse Estate, Wanda de Guebriant, about the drawing’s authenticity. She responded that the drawing was a forgery. Feigen returned his buyer’s $165,000 and asked Weil to return Feigen’s $100,000 purchase price. When Weil refused Feigen sued Weil for rescission of the sale contract on grounds of mutual mistake.18

Justice Moskowitz framed the issues as follows:

Although … both parties to the transaction at issue honestly assumed the drawing’s authenticity, Weil argues that the law requires that this court hold Feigen and Co. to the bargain it struck. Weil seeks to impose the cost of the mutual mistake on Feigen & Co. and avoid rescission [because] Feigen was “consciously ignorant” of the drawing’s authenticity; . . . . 19

Justice Moskowitz reasoned as follows:

The doctrine of mutual mistake retains its vitality today. Where a mistake in contracting is both mutual and substantial, there is an absence of the requisite meeting of the minds, and relief will be provided in the form of rescission. (citations omitted) The facts about which the parties are mistaken must be material. The parties’ mistake also must relate to facts in existence at the time of contracting.

The very purpose of the doctrine is to prevent the injustice that would arise when one party to a contract, realizing that a mutual mistake is to its advantage, seeks enforcement. By allowing rescission of unintended contracts, the parties can return to the status quo. Simply put, it is unfair to enforce a contract that neither party intended to make.20

Weil argued that Feigen was “consciously ignorant” of the authenticity of the drawing, that is, Feigen had not made a mistake at all but had intentionally chosen not to investigate the drawing’s authenticity, even though Feigen could have easily checked with the Matisse Estate, and Feigen thereby assumed the risk of forgery. Justice Moskowitz’ response to Weil’s argument was that “Feigen and Weil both honestly believed that the drawing was a Matisse and neither assumed the risk that it was a fake. . . . both parties assumed a certain fact and both were mistaken.”

Weil had also argued that because Feigen was an art dealer and Weil was not, Feigen should bear the risk of mistake. But, said Justice Moskowitz, in a contract between an expert and non-expert, there is no authority for the proposition that rescission based on mutual mistake is not available to the expert. And Weil also argued that the risk of mistake should be imposed on Feigen because Feigen had ample opportunity to discover the facts to which the mistake relates, and chose not to do so. Indeed, Feigen had the drawing in his gallery for a month. To which the justice responded, “ . . . mutual mistake . . . is not modified by a showing that one party could more easily detect a mistake.21

Critique of Feigen Decision

Justice Moskowitz in her Feigen decision stated:

…, the cases cited by Weil all arise where the parties to a contract have in their bargain assumed a risk as to the facts underlying the transaction. They do not apply to transactions—such as the agreement here—where both parties, far from assuming any risk, mistakenly assumed facts underlying the transaction. …22

… Feigen and Weil both honestly believed that the drawing was a Matisse and neither assumed the risk that it was a fake.23

But the justice misstates the law of mutual mistake (as well as the nature of a sale of art). That is to say, in all “mutual mistake” cases the parties mistakenly assume facts. The whole law of mutual mistake turns on which party should bear the risk of the mistaken assumption. Yet the justice concludes that “neither [Feigen nor Weil] assumed the risk that it was a fake.” The justice’s statement was accurate in the most literal sense that the sale contract did not expressly discuss whether the sale could be rescinded if the work turned out to be fake. But Feigen well knew the Matisse fakes were very common and knew how to verify authenticity by checking with the Matisse Estate. He had both the means and opportunity to determine whether his assumption of authenticity was correct. Every sale of art involves assumptions about its authenticity. Simply because the sale contract was silent on the subject did not mean that Feigen had not assumed a risk that the piece was a forgery.

The well-established exception to mutual mistake doctrine means that a party can rescind a contract on the grounds of a mutual mistake only when the mistake is not one for which he bears the risk. And, one recognized situation where the party asking for rescission bears the risk and cannot rescind, is when he enters into a contract knowing that he has only limited knowledge of the important facts. Feigen argued that the conscious ignorance exception to the mutual mistake doctrine did not apply because “knowledge is limited in all contracts.” But the conscious ignorance exception does not arise merely because of mutual limited knowledge. It arises when the party requesting rescission of his contract has both the means and opportunity to learn the missing fact and, nevertheless, contracts in the face of his limited knowledge. This party is taking the risk of mistake upon himself.

Indeed, all mutual mistake cases involve “limited knowledge” on the part of both parties on the same important issue, but it does not follow that the court must return the parties to status quo when the mistake comes to light. Justice Moskowitz failed to address who bears the risk and simply assumed that, if there were a mutual mistake, (as there certainly was) rescission must follow—thereby allocating the authenticity risk to the seller, Weil.

The Feigen court concluded:

Weil’s arguments against the application of the mutual mistake doctrine all relate to Feigen’s status as an art dealer and are not applicable on this set of facts.24

The Feigen court’s conclusion that Feigen’s status as an expert art dealer was not “applicable” resulted in its misapplication of the mutual mistake doctrine. Feigen’s knowledge of Matisse, of Matisse fakes, and of ways to authenticate Matisse works, and his status as an expert art dealer are critical to any application of the mutual mistake doctrine. An expert art dealer should not be granted relief (by way of rescission) from a bad bargain where the expert dealer makes, at most, a cursory inquiry into the authenticity of the art the dealer buys from a collector.

Mutual Mistake—Its Relation to Contractual and Statutory Warranty Claims

Since Weil was not an art merchant selling to a non-merchant, the New York Arts and Cultural Affairs Law did not imply a statutory warranty of authenticity from seller, Weil. And, since Feigen had not gotten a contractual warranty of authenticity from Weil (and, perhaps, had not even requested a warranty), Feigen’s claim to rescind his purchase was mutual mistake. This absence of a seller’s warranty suggests (by itself) that Feigen took on the authenticity risk as buyer.

Oddly enough, if buyer, Feigen had gotten an explicit contractual warranty from seller, Weil, Weil might have argued under the 1978 Dawson v. Malina decision (discussed above), that Weil might have had a reasonable basis for his seller’s warranty (even if the Matisse drawing turned out to be a fake) and, therefore, Weil had not breached his seller’s warranty. Feigen would be left to argue that, under the mutual mistake doctrine, Feigen and Weil allocated the authenticity risk by means of Weil’s contractual warranty. But it seems odder for a buyer to be able to “plead around’ the seller’s contractual warranty by alleging mutual mistake. After all, the very purpose of the contractual warranty is to allocate the authenticity risk between the buyer and seller, and this same risk allocation (as discussed above) is at the heart of the mutual mistake doctrine.

Therefore, when there is a seller’s express or implied warranty, and, indeed, even when there is not (and the sale is on an “as is” basis), this analysis suggests that the parties have allocated the risk of authenticity, the mutual mistake doctrine either should not apply at all on the question of attribution to the named artist, or at the very least, the warranty’s allocation of risk should be taken into account. However, New York courts have not explicitly stated such a rule, and unless and until they do, disappointed buyers will continue to assert mutual mistake claims, especially when their warranty claims are expired.

Two Mistakes: One by the Buyer, One by the Judge: the Feigen Decision Is Followed

A year after the Feigen decision, another New York court25 ordered rescission of a sale of a painting said to be by Bernard Buffet, which has been purchased by Uptown Gallery from a private collector and then discovered to be a forgery. The collector refused to return the purchase price on the ground that the gallery buyer had assumed the risk that the painting the gallery purchased was not what both buyer and seller believed it to be.

Justice Lobis in Uptown Gallery reasoned as follows:

Here, it is undisputed that both parties to the sale believed that the painting which was being sold was a genuine Bernard Buffet and that the purchase price for the painting was based on that understanding. It is also undisputed that the painting is a forgery and therefore has little value. Thus, there has been no meeting of the minds26 between the parties as to the sale of a Bernard Buffet painting.

Defendant argues that the doctrine of mutual mistake is inapplicable based on the “conscious ignorance” exception. According to defendant, plaintiff was consciously ignorant of the authenticity of the painting and thus cannot claim that the mistake was mutual. This very argument was raised in a similar case before Justice Moskowitz and was rejected. The seller of the painting in Feigen argued that the buyer, an art dealer, acted with conscious ignorance because it failed to authenticate a forged Matisse before purchasing it. Justice Moskowitz held that the conscious ignorance exception to the mutual mistake doctrine was inapplicable as this was not a case where “the parties to a contract have in their bargain assumed a risk as to the facts underlying the transaction. [The exception] does not apply to transactions—such as the agreement here—where both parties, far from assuming any risk, mistakenly assumed the facts underlying the transaction.” This court agrees with and adopts the reasoning of Feigen. This is not a case where the parties were uncertain as to a crucial fact, consciously ignored it and despite this uncertainty contracted. To the contrary, both parties entered into the contract based on the assumption that the painting being purchased was an authentic Bernard Buffet.

Nor does this court accept defendant’s argument that it would be more reasonable under the circumstances to place the risk of loss on the buyer. There is no reason why defendant should be entitled to a windfall based on its sale of a painting which was not what either party believed it to be. The painting was clearly not worth the contract price and there is no basis for allowing defendant to receive much more for the painting than what it is worth.27

But in 2001, the New York Courts Finally Get It Right (about Art Sales and Mutual Mistake) by Taking into Account the Parties Knowledge and Expertise—Hence, Informed Allocation of Authenticity Risk

The court decided that the parties, two sophisticated art dealers, had allocated the risk of mutual mistake to the buyer, and therefore the sale contract would not be rescinded.28 The gallery buyer had paid $100,000 to the defendant gallery for a half interest in a painting believed by both buyer and seller to be an authentic work of Thomas Dewing. After the purchase, an expert consulted by the buyer determined the work not to be authentic. In rejecting the buyer’s claim of mutual mistake, the court said:

. . .they [buyer and seller] all believed . . . that this was a legitimate Dewing painting, and this was so substantial and fundamental to the deal, that in learning it wasn’t a Dewing, that that fundamentally defeats the object of the contract . . .29

As to mutual mistake, . . . , I don’t think that applies here, . . ., based on the fact that we are dealing with sophisticated individuals and knowledgeable art dealers who it is clear by their various letters exchanged here were acknowledging that there are risks inherent in any such a deal vis-à-vis the authenticity of art.30

In sum, the court correctly evaluated how the parties had allocated the risk of a mistake.

Providing Context to Art-Related Cases: Mistakes in Non-Art Transactions

A brief review of court decisions involving issues, other than authenticity of visual art, will serve to further clarify the law of mutual mistake, as applied to art transactions.

The Restatement (Second) of Contracts31 takes the view that the party (buyer or seller) requesting rescission bears the risk of mutual mistake “when the risk is allocated to him by the court on the ground that it is reasonable under the circumstances to do so.” The parties’ expertise, knowledge, skills, ability, and opportunity to discover the fact to which the mistake relates contribute to a court’s decision allocating the risk of the mutual mistake—factors explicitly rejected by the Feigen decision discussed above.

Thus, Farnsworth on Contracts32 cites four land-use/sale cases. In the first, a builder contracted with the landowner to construct a building, and discovered the land contained rock ledge that made the construction much more expensive than both parties had anticipated. The court held that where the builder made no investigation into subsurface conditions, the builder could not rescind his contract with the landowner. 33

In the second Farnsworth case, the owner of farmland agreed to sell and then discovered that the land he was selling contained mineral deposits that made it much more valuable than both parties supposed. The court held that the landowner’s ignorance about the real value of the land did not entitle him to rescission on the ground of mutual mistake.34

Farnsworth, thought it

“more reasonable for the builder to bear the risk of mistake as to the presence of rock than to pass the risk on to the landowner, especially in light of the builder’s generally greater expertise in judging subsoil conditions [but thought it] ‘more reasonable for the landowner to bear the risk of the mistake as to the presence of minerals than to pass the risk on to the buyer particularly in light of the policy favoring finality of real estate transactions.’”35

And, a contractor made a bid for construction of a state highway, based in part on the state’s estimate sheet concerning where supplies of a stone could be found and their cost. After making his bid the contractor discovered that the cost of stone on the state’s estimate sheet was mistaken and stone (a major cost of highway construction) could only be obtained at much higher cost. The contractor sought relief from his contract and a return of money deposited with his bid. The New York Court of Appeals rejected the mutual mistake claim, reasoning that the bidder had the same opportunity as the state to discover the facts.36

In the fourth Farnsworth case, the New York Court of Appeals granted rescission against New York City and in favor of the contractor. Before contracting, the contractor did not have the means or opportunity to discover the existence of bedrock because the city’s engineers had themselves done the bedrock investigation and had asked for bids according to highly inaccurate plans based solely on the city engineers’ own examination.37

Rose, the Cow and the Bull Calf Cases, Explained—Maybe

Expertise, knowledge, skills, ability, and opportunity to discover the fact to which the mistake relates—factors which clearly played an important role in the four Farnsworth cases discussed above—may also provide the explanation for the contradictory results in Rose of Aberlone and bull calf. The bull calf was found to be sterile only on maturity—and perhaps only at that time were the means and opportunity available to the buyer to discover the accurate facts—so, aware of his limited knowledge at the time of sale, the buyer thereby assumed the risk and the court refused rescission, when risk became fact. With respect to Rose the cow, we do not know what the judge thought about the state of bovine scientific knowledge at the sale date in 1887, hence, what the judge thought the owner could have known about Rose before he sold Rose as a barren cow. But based on the analysis in this essay, we might assume that the judge thought that Rose’s owner did not have the ability or opportunity at the sale date to determine Rose was capable of breeding, and so, to the relief of her owner/seller, he rescinded her sale.

New York, New York

March 2015

Ronald D. Spencer

Carter Ledyard & Milburn LLP

Notes

1 Chimart Assocs. v. Paul, 66 N.Y.2d 570, 574 (1986).

2 Gould v. Bd. of Ed. of the Sewanhaka Central High School Dist.., 81 N.Y.2d 446, 453 (1993).

3 Restatement of Contracts 2d § 154(a).

4 FSP v. Societe General, No. 02-CV-4786 (GBD), 2005 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 3081 (S.D.N.Y. Feb. 28, 2005).

5 Beecher v. Able, 575 F.2d 1010, 1015 (2d Cir. 1978).

6 FSP, 2005 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 3081 at *48.

7 E. Allen Farnsworth, Contracts §9.3 (Mutual Mistake) (1982).

8 Sherwood v. Walker, 66 Mich. 568, 33 N.W. 919, 924 (Mich. 1887).

9 Backus v. MacLaury, 278 A.D. 504 (4th Dep’t 1951).

10 See also Leasco Corp. v. Taussig, 473 F.3d 777, 781-82 (2d Cir. 1972).

11 New York Arts and Cultural Affairs Law § 13.01. For multiples such as editioned prints, photographs, and sculpture, the law provides a broader warranty which applies “[w]hen an artist furnishes the name of the artist of a multiple,” extends to purchasers who are art merchants, and specifies that a reasonable basis in fact is not a defense.

12 Dawson v. G. Malina, Inc., 463 F. Supp. 461 (S.D.N.Y. 1978).

13 Where the buyer’s warranty claim (as to title or authenticity or both) is time-barred after four years, the time-barred warranty claim is still relevant to a court’s allocation of risk under the mutual-mistake-of-fact doctrine. Certainly the seller and buyer expressly agreed in the warranty on the allocation of risk, such that where both buyer and seller were mistaken, the seller, having given his warranty, should bear the risk of the mistaken assumption of fact. See U.C.C. § 2-303 (Allocation or Division of Risks) (“Where this Article allocates a risk or a burden as between the parties ‘unless otherwise agreed,” the agreement may not only shift the allocation but may also divide the risk or burden.”).

14 ACA Galleries, Inc. v. Kinney, 928 F. Supp.2d 699 (S.D.N.Y. 2013), aff’d, 552 Fed. Appx. 24 (2d Cir. 2014).

15 It is not clear that introducing a negligence concept is useful in allocating risk of mistake between contracting parties. It seems preferable to examine this as a missed opportunity for due diligence by the party requesting rescission.

16 ACA Galleries, 928 F. Supp.2d at 701–702 (citations omitted).

17 ACA Galleries, 552 Fed. Appx. at 25.

18 Richard L. Feigen & Co. v. Weil, Index No. 13935/90 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. N.Y. County Feb. 18, 1992), aff’d, 1993 N.Y. App. Div. LEXIS 2395 (1st Dep’t March 16, 1993) (“unanimously affirmed for reasons stated by Moskowitz, J.”).

19 Feigen, slip op. at 5–6.

20 Feigen, slip op. at 7–8.

21 Feigen, slip op. at 12.

22 Feigen, slip op. at 8.

23 Feigen, slip op. at 9.

24 Feigen, slip op. at 14.

25 Uptown Gallery, Inc. v. Doniger, Index no. 17133/90, 1993 N.Y. Misc. LEXIS 661 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. N.Y. County March 9, 1993).

26 See discussion supra re ‘meeting of the minds’.

27 Uptown Gallery, at *2

28 Findlay v. Zaplin Lampert Gallery, Index No. 603118/01 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. N.Y. County December 19, 2001) (Schlesinger, J.).

29 Findley, slip. op. at 3.

30 Findley, slip op. at 7.

31 Restatement of Contracts 2d § 154(c) (1981).

32 Farnsworth § 9.3.

33 Watkins & Son v. Carrig, 21 A.2d 591, 91 N.H. 459 (1941).

34 Tetenman v. Epstein, 226 P. 966, 66 Cal. App. 745, 66 Cal. 745 (1924).

35 Farnsworth, § 9.3.

36 Semper v. Duffey, 227 N.Y. 151 (1919).

37 Faber v. City of New York, 222 N.Y. 255 (1918).

Editor’s Note

This is Volume 5, Issue No. 2 of Spencer’s Art Law Journal. This winter issue contains three essays, which will be available on artnet in March 2015.

The first essay (Mistakes Were Made) discusses the often-made claim of mutual mistake by both seller and buyer about the authenticity of art sold, and whether the sale can be rescinded by the disappointed buyer.

The second essay (It’s Becoming Easier to Get Your Consigned Art Back from the Bankrupt Gallery) examines consigning art to a gallery. One of the risks is the bankruptcy of the gallery (think Salander-O’Reilly). Getting your art back from the bankruptcy trustee may be getting easier.

The third essay (Legal Liability of Art Experts—Is Insurance a Solution and Will Opinions Be Less Dangerous Things to Give?) is an introduction to the use of insurance as protection for the art expert. This kind of protection should encourage opinions from experts.

Three times a year, this journal addresses legal issues of practical significance for institutions, collectors, scholars, dealers, and the general art-minded public.

— RDS