Just over a decade ago, the high-flying art market seemed unstoppable. Damien Hirst’s now-famous (or infamous?) evening sale at Sotheby’s London, titled “Beautiful Inside My Head Forever,” raked in just over $200 million on September 15, 2008. Even the sudden collapse of storied investment bank Lehman Brothers earlier the same day didn’t halt bids from dozens of eager buyers, including one who shelled out the top price of $18.6 million for Hirst’s formaldehyde-tank sculpture The Golden Calf.

But just a few weeks later, the market looked radically different. New York’s fall auction season experienced a precipitous drop after many top works went unsold, and an extended downturn followed. Though the US National Bureau of Economic Research marked the official end to the recession in June 2009, it took far longer for the art market—by its nature, a lagging indicator—to rebound.

Today, eerie comparisons to the pre-recession economic landscape of 2007 seem to be everywhere. Some economists have flagged a slowdown in real GDP growth, an inverted yield curve, and a pair of recent Federal Reserve interest-rate cuts as cause for concern. And with the knowledge of how quickly and severely the financial landscape can quake, some art-market veterans of the Great Recession are once again bracing for the possibility of a shake-up.

So what lessons were learned from the previous market downturn? And can they help cushion the blow of another bout of extended turmoil in the art trade? We talked to several dealers about how to weather the hard times.

Damien Hirst’s The Golden Calf on display before the “Beautiful Inside My Head Forever” Sale at Sotheby’s in 2008. Photo courtesy of Peter Macdiarmid/Getty Images.

1. Tighten Your Belt

Jay Gorney, who recently joined Marlborough Gallery as a senior director, compared his experience during the 2001 downturn with the more recent economic crisis just over a decade ago.

“In 1991, at the time of the Gulf War, I had my own gallery, and we really felt the recession,” he says. “I remember feeling it more than I did in 2008, when I was a director at Mitchell-Innes & Nash.” In the earlier downturn, it became a case of “belt-tightening and unfortunately needing to sell things from my inventory.” The best advice he can give younger gallerists is “to be careful and prudent, especially in how quickly they expand.”

artnet News columnist and art dealer Kenny Schachter concurs. “Cut costs to the bare-bone minimum,” he says, advising a sharp scale-back on art-fair participation—or, as he calls it “a fair pare.”

Another of his tips? “Band together with friends and coordinate openings, brunches, whatever to make it as easy as possible to facilitate and entice gallery-goers.” Collaboration can even be a part of a “fair pare” strategy, as creative partnerships with galleries in other cities or countries can provide some of the same benefits at a fraction of the costs.

2. Bargain Hard With Suppliers

One of the keys to negotiating is that you should always ask for what you want, even if you don’t think it’s realistic… because sometimes you get it anyway.

Candice Madey put this lesson into action immediately upon opening her Lower East Side gallery On Stellar Rays in 2008. Less than a week after the gallery’s debut, Lehman Brothers collapsed, bringing the long-gestating financial crisis into startling visibility. Understanding the severity of the situation, Madey marched to her landlord’s office the same day and bargained her way to a 40 percent discount on her rent.

Madey admits now that she was “surprised” at how accommodating her landlord was. “I think he understood [this situation] was serious and could affect the business,” she says. But it’s likely that she would never have known if she hadn’t been bold enough to test the boundaries of her original five-year lease in the first place.

“He said, ‘We’re only going to do this [discount] for a few months,’ and then he kept trying to bring it back up to where it was supposed to be,” she says. “So every month I was walking down to his office and haggling.” It paid off, as the gallery survived the recession and continued on for roughly a decade after. (Madey voluntarily closed the gallery and shifted to a nomadic, project-based initiative called Stellar Projects two years ago.)

She took a similarly tough stance when it came to subscription-based services. For example, she says she “negotiated really hard” to buy her inventory-management software outright instead of paying a monthly fee in perpetuity (which is always designed to benefit the provider by locking in predictable income).

“When you’re open and making sales, it’s easy to make those [monthly] commitments,” Madey says. But there is no better time to negotiate than when you’re still operating from a position of strength.

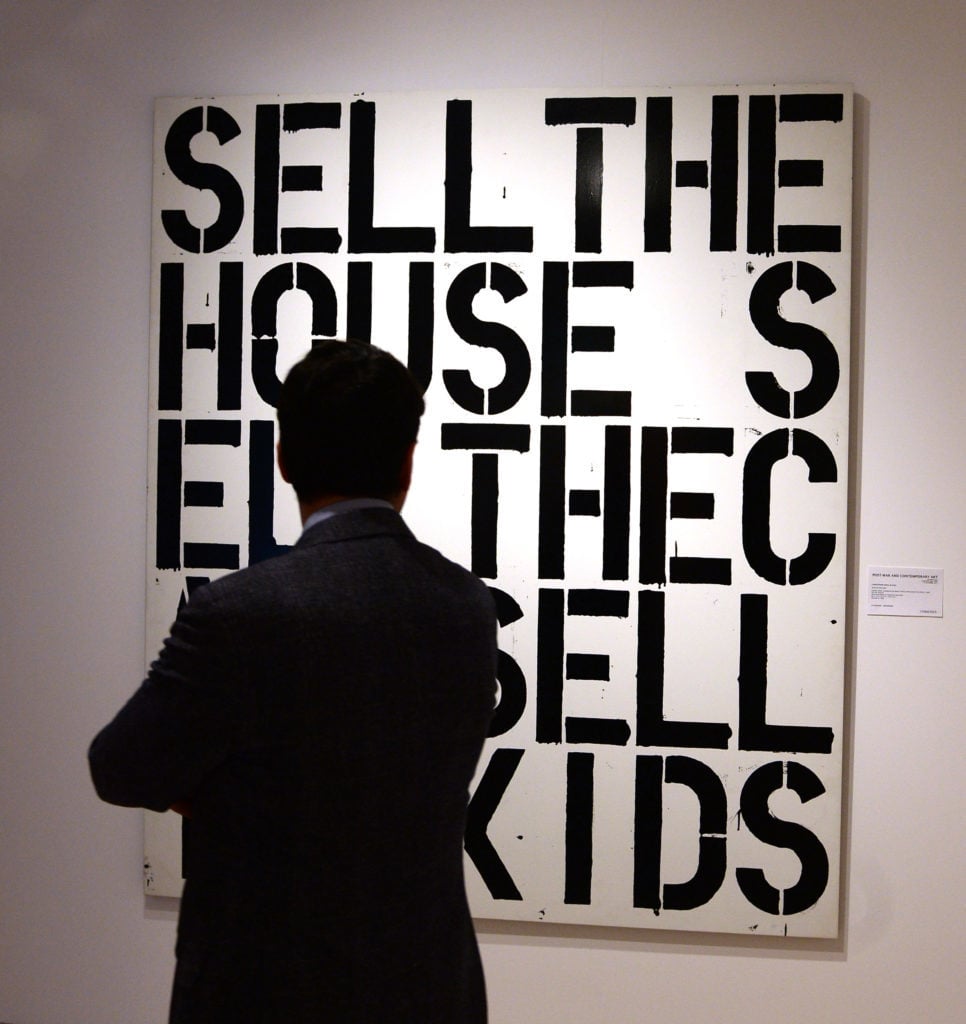

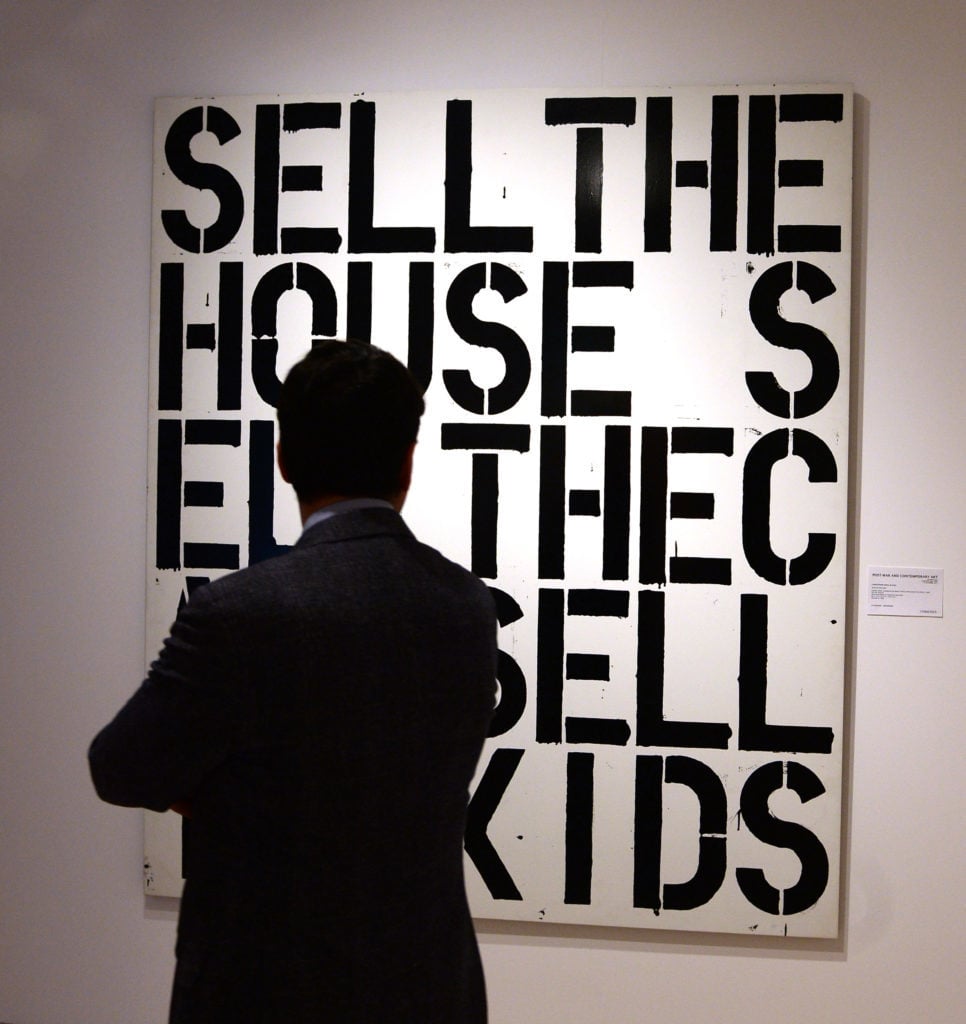

Christopher Wool’s Apocolypse Now at Christie’s. Photo by rune hellestad/Corbis via Getty Images.

3. Buy Art If You Can (and Buy as Much as You Can)

Joel Mesler, who ran a successful Lower East Side gallery for years before closing and decamping to Eastern Long Island where he organizes shows, including some of his own work, says: “What the smart people do is buy lots of artwork. The people that really made money [in the last recession] were the ones that bought at that first auction [after the market fell] where works were selling at 35-to-45 percent under market. They just cleaned house.”

Gorney is also a proponent of always buying too: “Always collect—buy works if you possibly can. So often, some of your greatest profits will come from the sale of inventory work.”

4. Don’t Count on Loyalty

There are two sides to this advice from Edward Winkleman, who co-founded Plus Ultra Gallery with artist Joshua Stern in Brooklyn’s Williamsburg neighborhood in 2001, then converted the space to Winkleman Gallery in Chelsea from 2006 until mid-2014.

The first side concerns the relationship between dealers and buyers. Winkleman emphasizes that most major (or even semi-major) buyers simply collect too widely to prop up every artist—or for that matter, every gallery—during lean times.

“The biggest misconception is that the collectors share the gallery’s concerns about [any] artist’s long-term market,” explains Winkleman. “I’ve seen dealers appeal to reluctant collectors with the argument, ‘But the artist needs some sales,’ just to find the argument fall flat.”

An equally important loyalty lapse concerns the artist-gallery relationship. In his book Selling Contemporary Art: How to Navigate the Evolving Market, Winkleman conducted an informal analysis of how many artists moved between galleries or exited gallery rosters completely in the years between 2008 and 2014.

He found that what he classified as mid-level galleries—the ones most vulnerable to a financial downturn—retained only about 54 percent of their artists on average, while higher-level galleries retained nearly 70 percent.

Although Winkleman says he attributes these results more to “a shift in expectations about long-term relationships” in the 21st century gallery economy than to the financial pressures of the Great Recession, he does offer an important caveat.

“It seems highly probable to me that artists or gallerists who were used to strong sales before 2008 concluded, ‘It’s you, not me’ when sales dipped after 2008″—leading to artists jumping ship or dealers cutting ties with artists whose work sold poorly.

5. Consider Complementary Revenue Streams

Multiple dealers stressed the value of capitalizing on a gallery’s existing resources to find new sources of income in challenging times.

Winkleman weathered the Great Recession partly by establishing an editions program within the gallery. “That kept our artists’ names fresh in our collectors’ minds and helped bring in steady cash flow,” he says. Madey began offering On Stellar Rays for film and photo shoots at a rate of $1,000 per day, an even more sizable sum a decade ago than it is today.

Don’t feel self-conscious about making these kinds of moves, either. After all, Gavin Brown kept the lights on in his former Chelsea space for roughly eight years partly by running the beloved bar Passerby out of its front end.

Empty shelves line a closed Woolworths branch after the last day of business in London on January 6, 2009. The retailer failed to find a buyer in administration, forcing the closure of over 800 stores and the layoff of over 27,000 workers. Photo by Peter Macdiarmid/Getty Images.

6. Yes, You Can Temporarily Reduce Prices

Winkleman rejects the art-market myth that primary-market prices must only ever stay steady or rise, even during a recession.

“A gallery is a business and of course you can lower prices with care,” he says. “You’ll have to endure some grumbling, but the logic in doing so is sound.” Again, everything is negotiable. And remember: listed prices can even technically stay intact if a dealer just removes the usual limits on the size of the behind-the-scenes discount they’re willing to offer.

7. Take Advantage of Cheap or Free Technology

“Use Instagram, it’s free and it works to promote artists and individual works,” Schachter says. “I sold an expensive work in a recent show via Instagram.”

Even anecdotal evidence from buyers backs this up. Several years back, during a panel on Instagram at Art Basel Miami Beach, Swizz Beatz, artist Daniel Arsham, and dealer Simon de Pury stressed how integral Instagram had become in their daily lives, from discovering new talent to promoting work.

De Pury relayed a hilarious story about the free service’s ability to shape perceptions of the market: “So there is this fantastic restaurant in London called Novikov. There’s a beautlful bar, and the bar has such an incredible pattern. So I made a close-up of that pattern and I just put #Novikov [as the caption]. I had six or seven people call me up asking: ‘How can I get a painting by Novikov? How can I acquire one of his works?’ So it’s actually quite a powerful tool.”

8. Double Down on Your Program

Although it’s wise for galleries to be ultra-conservative about their expenses during an economic downturn, it can be just as wise for them to be adventurous with their exhibitions.

“I think a lot of galleries get confused, scared, and start showing what they think will sell,” Madey says. But this approach tends to backfire in a recession, as it forces dealers to market works that don’t excite them to a clientele disinclined to buy anyway.

Instead, she argues that an economic downturn is an opportunity to “set your gallery program apart and present an authentic voice” that has a better chance of connecting to an audience.

In short, every show is a risk in a recession, so it’s better to at least take the risks that can build your brand.

Just don’t think this mindset will work in every context. Winkleman says he thought “statement” booths at art fairs would generate as much press and positive benefits as statement exhibitions in his gallery.

He was wrong. “We often left a fair with nothing close to breaking even, and that helped sink us in the end.”

Job seekers wait in line to enter the San Francisco Hire Event job fair on November 9, 2011. Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images.

9. Recognize That the Last Recession Is Still With Us

“Never mind what’s coming down the pike. we’re actually still dealing with effects of the 2008 economic crisis,” says veteran dealer Jane Kallir, director of Galerie Saint Etienne.

“The rise of the one percent is something that has happened gradually, over the 40 years or so that I’ve been in the business. There was a time when that was good for the art market because it created more people who had the wherewithal to collect.”

But Kallir says that as the money began to pool more and more at the top of the art market, and auction houses and bigger dealers were chasing that limited pool, “the middle market got hollowed out, just like the middle class got hollowed out. That is much more the fundamental problem that we’re dealing with today.”

Kallir emphasizes that each situation is different and that it’s tough to generalize, but she sees the pronounced trend of middle-market gallery closures as a reflection of the 2008 fallout.

“We’re adjusting to the fact that there are no middle-class collectors,” Kallir says. “The question is, how much art do you need to sell, and at what price point, to maintain a gallery in a major city and do the minimum number of art fairs in order to stay in business? If galleries can figure out a way to solve that, they’ll get through the next recession.”