Auctions

Art World Report Card: Basquiat in the Bayou, the Adam Sender Collection, and Joe Bradley at Auction

How an artist enters the star-making machinery.

How an artist enters the star-making machinery.

Alexandra Peers

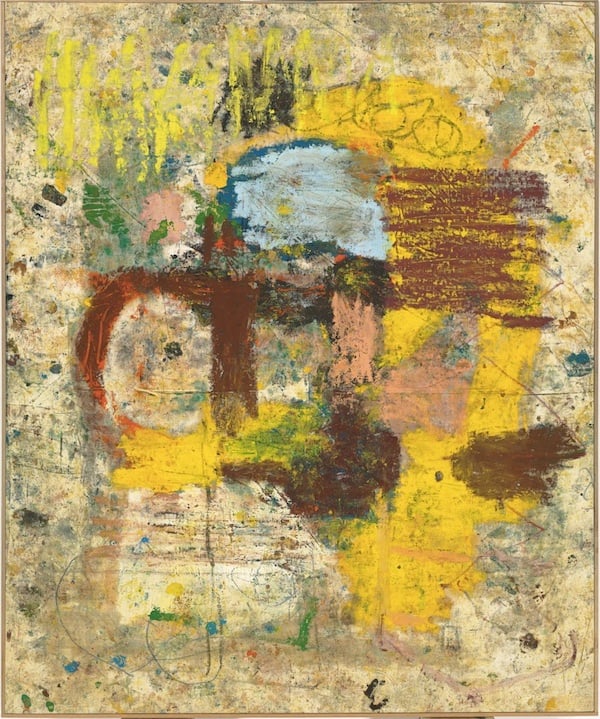

Joe Bradley’s Blonde (2011) sold for $965,000 at Christie’s New York on the evening of May 12, 2014.

Photo: Courtesy Christie’s.

Orchestrating the Art Auctions

“I have lots of interest here,” announced the auctioneer at Christie’s, zippily, and that was an understatement.

Joe Bradley, whose art variously invokes figuration, Primitivism and the “new abstraction,” (ah, the art world loves a movement), had a painting, Blonde, on the auction block. It soared to just under $1 million. That was one of several artist’s records set May 12, although in a couple of cases the margin of success was just a suspicious smidge above the last record, a happy coincidence, if you believe in such things. Which we don’t.

Certainly, the major spring and fall art-sales seasons are well-choreographed and strategized months in advance. Here’s how it works: The market is first tested for a particular artist, either new or ripe for a run or for rediscovery, with one of his more emblematic or attractive pieces. If the match is struck, the race is on. Ever-more difficult or pricey work comes out on the market. These pieces are somewhat pre-sold, by email, before they ever hit the auction block, to ensure success. (i.e., there’s a flurry of February emails: “Do you have a client who would be interested in this at $50–80k?”). The headlines bring other works out of the woodwork. Then savvy dealers or collectors who may have been stockpiling sell into the price climb, and so onwards and upwards.

From Caillebotte to Condo, it’s an old story, with everybody chatting with each other at Sant Ambroeus. The only new twist now is that, for the flagship works there are investment opportunities to be had for guarantors. The guarantors can place bets on the degree of bidding they expect without ever acquiring the “asset.” It’s the Freddie Mac–ing of art.

Sure, at these sales, the suspense is real, but it has more to do with whether a recession, war, or would-be buyer’s regret will hit before the grand performance can play out.

Such was the treatment, given this season to Keith Haring (a major marketing push is going on for this spiritual father of graffiti art), to Julian Schnabel, to Chris Ofili, to Joe Bradley. These artists were sometimes offered for sale at estimates which would in of themselves set records, a pushy stratagem. The auction houses push the prices because the market will take it but also because departmental compensation hinges on performance. Particularly at Christie’s, insiders say, arguably unrealistic targets are prompting higher and higher estimates and more fevered sales pitches. It’s working: Christie’s raised a jaw-dropping $744.5 million earlier this week in a single sale, in some cases aggressively supported by the dealers who represented the artists in the auction.

Four major and rare black-and-white Warhols—a Marilyn, a Beuys, a Mona Lisa, a Jackie—came to market this season, through auctions and galleries. Coincidence? I have a bridge to sell you. Or, more specifically, a white Warhol.

Consider the vibrant art of the Maine-born, Brooklyn-residing Bradley, born 1975. His price climb seems as much orchestrated as organic—but certainly swift. He started out showing at a quarter of well-liked or powerhouse galleries: Kenny Schachter, Peres Projects, Canada, and Gavin Brown. First appearing at auction in 2010, his work bought in then at a $5,000 estimate. A larger work showed up at Phillips six months later and sold for three times’ the estimate, or $60,000. Bradley’s art was offered in sales at Phillips and Christie’s South Kensington several times in 2010–11. It “graduated” to a Christie’s evening sale in October 2011, then selling for about $80,000. By November 2012 he was bringing $206,000 at Sotheby’s. Then MoMA Curator Laura Hoptman, whose husband also happens to show at Gavin Brown, interviewed Bradley for Interview magazine. (It’s a small world.) By 2013, a work he had done the same year sold for $658,000 at Phillips.

This week, all three auction houses had his works included in sales. Joe, Welcome to the machine.

Out of Fad, Due Back in Fashion?

Now, if you have been seized by bidding fever as a result of all this, here’s a cautionary tale. The Adam Sender Collection, dubbed at Sotheby’s “ahead of the curve,” is still apparently too far ahead of it, and a lot of it ended up in the (shudder) day sale. Which doesn’t mean the financier/voracious collector won’t make a mint, if that was indeed his goal—but he had to buy a lot of lottery tickets to do it.

For those who truly want to be ahead of the curve, there are two artists in the May 15 Sotheby’s day sale which, judged by their white-hot status a decade ago, may be ripe for rediscovery with the next turn of the wheel. (We don’t promise profit here, not remotely, but thoughtful art which fashion may have forgotten.)

Barnaby Furnas’s $60-80,000 Drummer Boy (2008)—a painting of the tiny title figure heading with Confederate soldiers into a hail of bullets—just may represent a bargain. Furnas exploded onto the art-world scene a little over a decade ago with his memorable, candy-colored battle scenes. Think history painting meets the Vegas Ultra-Lounge school. By 2006, there was a profile of him in the New Yorker. He’s had more than a dozen works at auction sell for six figures, one large one for $520,000. In more recent years, there’s been a couple of buy-ins. But aesthetically, in a post 9/11 harsher art world that favors the harshness of Francis Bacon and Cady Noland, Furnas’s paintings, known for their crimson tide of blood, may have a place.

Works by Stephan Balkenhol, a Charles Saatchi favorite of about 15 years ago, can be had starting at $40,000. (In 2006, Art Forum praised his “provocative disjunctions” and said the artist has “overlaid the question of figuration and the body with a spare, Conceptualist aesthetic, which has since resulted in an oeuvre both wry and serious.”) Three dozen of his sculptures—rough-hewn wooden figures on plinths—have sold for more than $75,000. And there’s a bet to be made that in the current vogue for authentic art, (plastic art is out; note the missing Murakami at auction) Balkenhol’s work will be re-evaluated. There are a lot of his sculptures, true, but, in a world where artists are desperately trying to set themselves apart with a signature style, a Balkenhol is recognizable a mile away.

Basquiat on the Bayou

At a press conference May 15, New Orleans Prospect.3, the popular contemporary art bi/triennial started in the wake of Kartrina, is expected to announce the artists who will take part this fall. Star Theaster Gates is among them, but a real draw may be a fresh look at an almost over-shown master. “Basquiat on the Bayou,” overseen by Franklin Sirmans, Prospect.3 Artistic Director and head of contemporary art at Los Angeles County Museum of Art, will take a look at Jean-Michel’s tour of the South shortly before the artist’s death in 1988.