Art World

Mel Bochner’s ‘Strong Language’ at the Jewish Museum

Pretty words, dirty words, all the words you want.

Photo: Rebecca Lax.

Pretty words, dirty words, all the words you want.

Eileen Kinsella

In 1964, as a young artist fresh out of school, Mel Bochner left Pittsburgh for New York. He landed a job as a security guard at the Jewish Museum and lasted there for about a year before he was caught napping behind a Louise Nevelson sculpture and unceremoniously fired.

Fifty years later, Mr. Bochner is back in the museum in a radically different capacity. His works are the subject of a major survey titled “Strong Language,” featuring more than 70 he created between 1966 and 2013 that reflect his continuing fascination with language.

Two days before the May 2 opening, the conceptual artist sat down with Norman Kleeblatt, the museum’s chief curator and organizer of the show, for a brief, insightful discussion about how his work with language as a central theme has developed and changed over time.

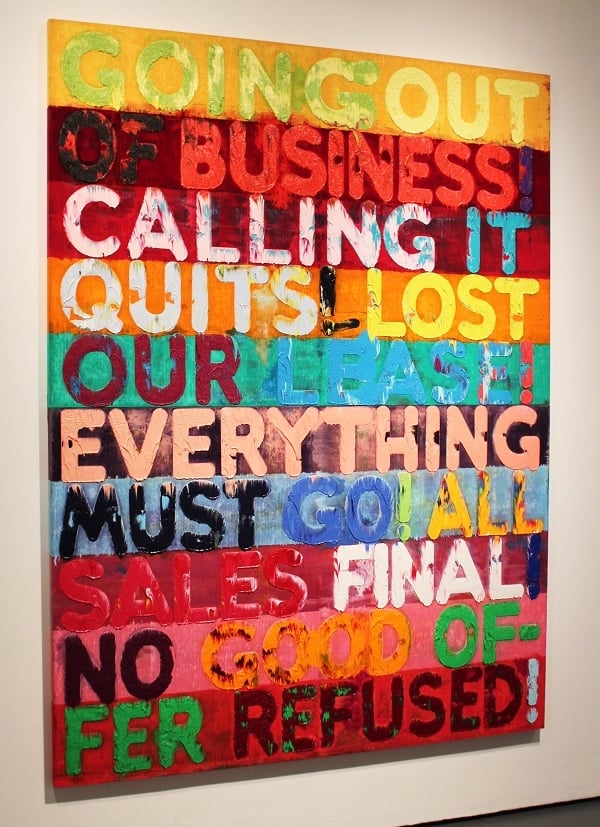

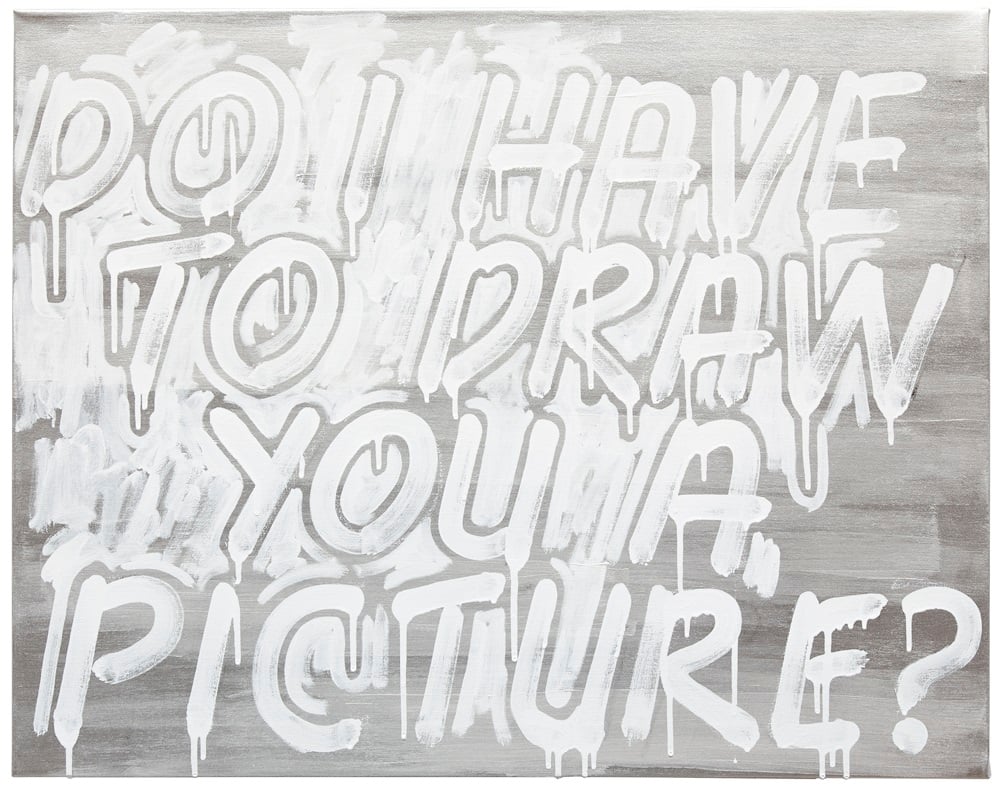

Many observers are familiar with Bochner’s now iconic and more recent “Thesaurus” series of paintings, which he began in the early 2000s.

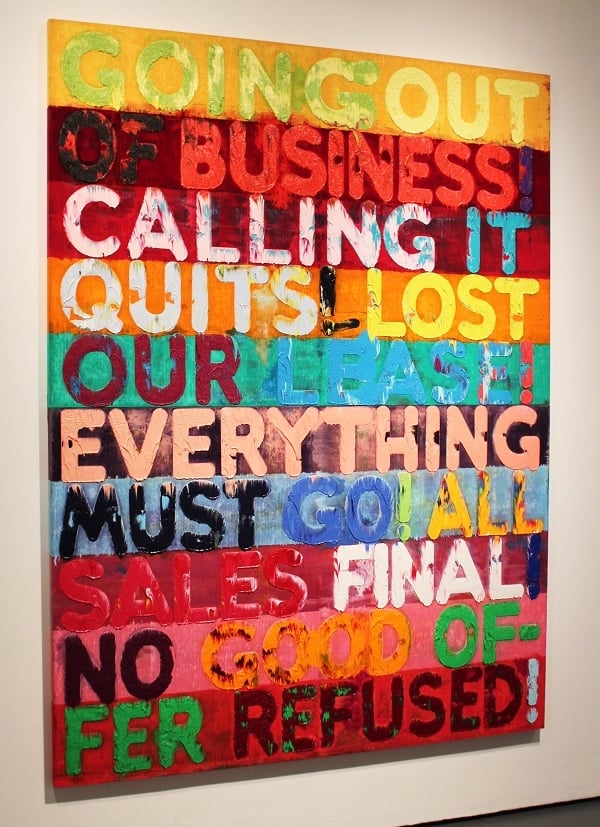

These large paintings plumb the meaning of a single phrase or term, with multicolored words and phrases that look like they may have been auto-generated by a computer but for the undeniable signs of handpainting: rich texture, lush colors, and deliberate paint smears and drips. Hyphens break words randomly. Some color schemes, where the color of the letters match too closely the brightly hued band of background color, render letters invisible, forcing the viewer to look closer in order to discern certain words.

Mel Bochner painted Jew (2008) after coming across a website with a list of antisemitic synonyms for the word “Jew.”

Photo: Rebecca Lax.

Many of these works inevitably prompt laughter, as typical expressions like “No” and “No Way” devolve into slang and curses like “Never Happen,” “Fuck Off,” and “Drop Dead.”

While these witty—and now very well known—works occupy a major and well-deserved place in the show, considerable attention is also focused on Bochner’s 1960s conceptual work, demonstrating his early exploration of language as a means of representation at a time when he had mostly shunned traditional methods of painting.

In Misunderstandings (A Theory of Photography) (1967–70), nine texts handwritten by Bochner on note cards each record a statement about photography, supposedly from luminaries like Marcel Duchamp and Emile Zola.

There is this from Encyclopedia Britannica: “Photography cannot record abstract ideas.” Bochner made offset lithographs of the notecards and, further toying with issues of authenticity and truth, reveals that three of these quotes are his own invention, though we are not told which.

“Misunderstandings is an understatement: the work is composed of partial truths and outright fictions that demonstrate the unreliability of both text and technology,” according to the exhibition catalogue.

Also a revelation are his 1966 text portraits of fellow artists Eve Hesse, Dan Flavin, Ad Reinhardt, Robert Smithson, and others, all of which conspicuously lack graphics. Hesse’s portrait for instance, consists of ink on a circular piece of graph paper with concentric lines of single words in the artist’s neat block lettering: “CLOAK,” “BURY,” “OBSCURE,” “VARNISH,” “ENSCONCE,” and so on. These spiral to smaller and smaller sizes ending in the center with a single word: “WRAP.”

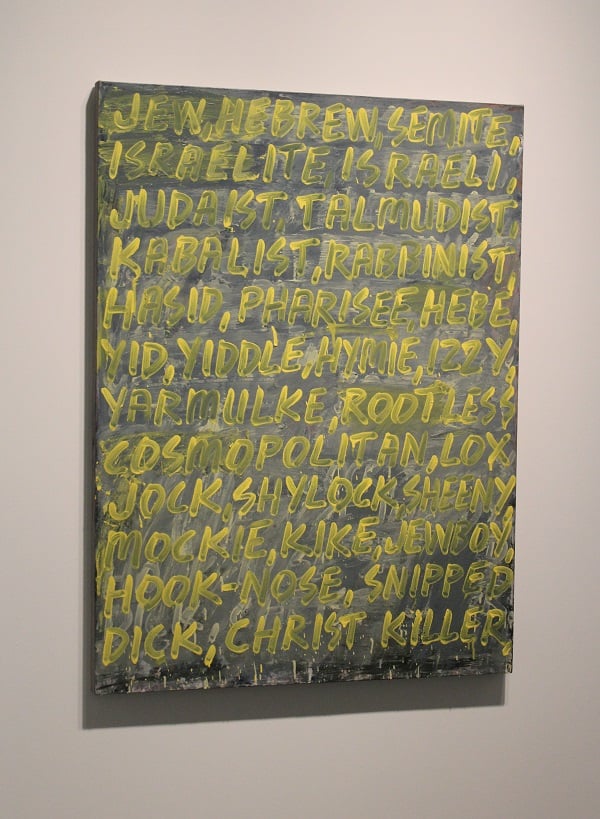

Mel Bochner, Do I Have to Draw You a Picture (2013). Private collection. Photo: Courtesy Jewish Museum. Artwork © Mel Bochner.

Discussing these works, Bochner explained to the audience: “In the mid-’60s, a certain level of doubt appeared in terms of what representation was. Those little portraits developed from the idea that if you can no longer draw a portrait of someone, within the accepted restrictions that you place on your own work, then how can you represent them? In the case of those works, the answer to me was language. Language is in fact a form of representation.”

Portrait of Dan Flavin (1966), also ink on graph paper, looks like one of Flavin’s fluorescent light sculptures turned on its side. Words horizontally running the length of the uneven lines read in part: “The discovery that both light and matter have wave and particle characteristics…”

One audience member pointed out that a “preponderance of conceptual ideas” has always run through Bochner’s work. By turns self-effacing and thoughtful, he replied, “Can you tell me what those ideas are?” However, the artist went on to concede his belief that, “All art is conceptual. Art is ideas. How to manifest those ideas is up to each individual artist.”

When Kleeblatt asked Bochner if more painting, specifically the “Thesaurus” paintings, represented a “different path,” the artist replied, “In the ’60s I could never imagine painting my ideas. At some point I had to ask myself ‘Why can’t I? What is it that’s denying me permission?’ Of course it’s oneself that is denying one permission. So one of the ways you enlarge the scope of your work…is that you the artist give yourself more and more permission.”

Another gem on display here is Bochner’s handwritten 1966 list entitled Minimalist Art — The Movie. The list is a proposed cast for the film: Jackie Gleason as Flavin; Sean Connery as Donald Judd; Jason Robards as Sol LeWitt; Frank Sinatra as Leo Castelli; Elizabeth Taylor as “Virginia” (presumably Dwan?); Jack Lemmon as Robert Mangold; and Peter Fonda as Mel Bochner.

“Dialogue and Discourse: Mel Bochner and Norman Kleeblatt,” a public event on Thursday, May 15, at the Jewish Museum, 1109 Fifth Avenue, features a discussion between the artist and the museum’s chief curator. “Mel Bochner: Strong Language” is on view through September 21, 2014.