Auctions

artnet Asks: Damian Hackett on the Expanding Aboriginal Art Market

Hurry to Deutscher and Hackett's upcoming May 25 sale.

Hurry to Deutscher and Hackett's upcoming May 25 sale.

artnet Auction House Partnerships

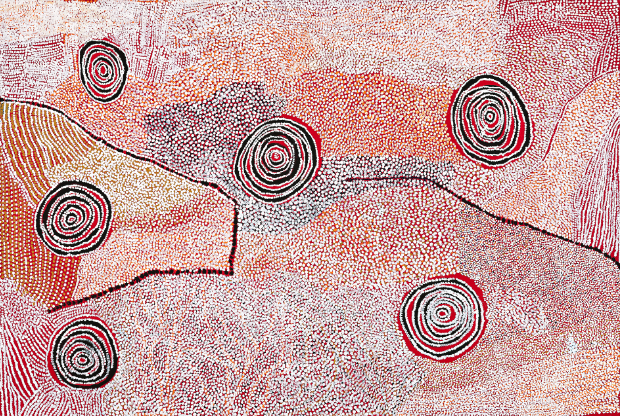

Bill Whiskey Tjapaltjarri, Rockholes Near the Olas (2008). Courtesy of Deutscher and Hackett.

Deutscher and Hackett is a leading auction house in Australia, with offices in both Sydney and Melbourne. Helmed by two founders who come from a background of gallery work and private dealing, this auction house brings a fresh approach to the secondary art market. Not the least of which are their stunning Aboriginal art auctions, the next of which, Important Aboriginal Works of Art, will be held this May 25 in Melbourne and features a variety of 20th- and 21st-century pieces offering a vibrant selection of innovative abstraction.

Here, we ask Sydney-based Executive Director Damien Hackett about their upcoming sale, what makes contemporary Aboriginal art unique, and how collectors can approach this booming market.

You have regular Aboriginal art auctions and are among very few houses worldwide who specialize in this market. Would you consider this market as niche or expanding?

We are very proud of our stand-alone Important Aboriginal Art auctions, which we’ve now presented continually for nearly a decade. Deutscher and Hackett is the only auction house in Australia to do so.

It took us a year before we were able to secure the head of our department, Crispin Gutteridge, who is the possibly the most experienced and respected Aboriginal Art auction specialist in the world. We are very strict about the quality of the works we handle, as well as their original source.

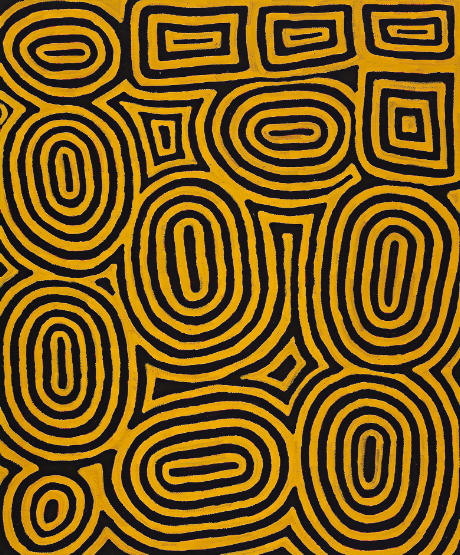

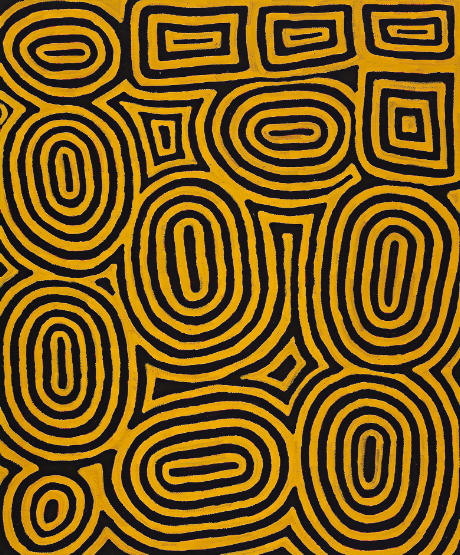

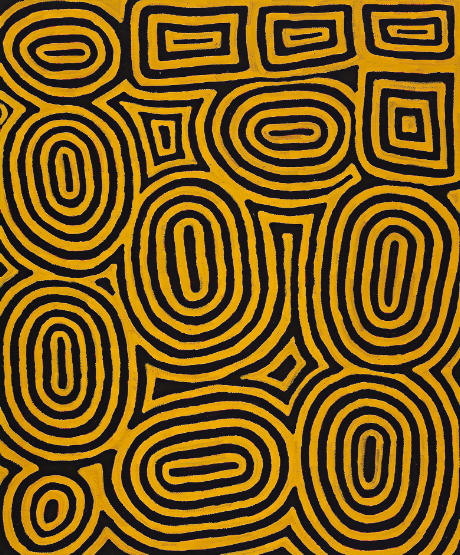

Ronnie Tjampitjinpa, Tingari Cycle (1997). Courtesy of Deutscher and Hackett.

The Aboriginal art of Australia is incredibly rich, visually exciting, and intellectually stimulating, with the discussions surrounding it delving into spirituality, aesthetics, and politics. After the Global Financial Crisis—when a number of market-damaging decisions by the former government combined with a skyrocketing Australian dollar—the market for Aboriginal art, both domestically and internationally, did hit a few big potholes. Now, however, the market has readjusted and, I think, as a result of some extremely good-quality collections are coming to market, such as the Laverty collection. There has been a renewed interest and enthusiasm for Aboriginal art, which is very positive.

Also, the fact that the Australian dollar is back to a sensible level, interest in our indigenous art from international collectors is also now returning, but there is a ways to go before the prices achieve their pre-2008 levels on the whole.

What is your advice for buyers who want to start collecting this type of work?

To enter into the Aboriginal market is somewhat the same as the non-Aboriginal market: look and learn. As always, don’t hold back when asking questions of the auction house or dealer. Even though contemporary Aboriginal art is ‘young,’ provenance is of great importance.

But while there are some very good collections of Australian Aboriginal art overseas, some museum collections do still only hold a small representation of mainly historical artefacts. While these are important objects and they provide pathways into the language and symbolism, contemporary Aboriginal culture has not only endured the last 200-odd years of post-colonisation, but is one of the most fertile and evolving cultures on earth.

What has happened since the early 1970s is remarkable. The use of contemporary materials has provided us with a unique opportunity to experience the regional visual languages of Australia and the ancient stories of universal connectivity, of family, of home, of survival and of celebration.

But, ironically, international collectors have an advantage in that Australians, in general, are far less accepting of abstraction! When artists like Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Rover Joolama Thomas, Paddy Nyunkuny Bedford, Ronnie Tjampitjinpa, and the contemporary painter Daniel Walbidi—most of whom had never seen an international art textbook—can produce the most remarkable contemporary abstraction that has ancient foundations, we have a truly timeless and enduring art. However, some of the biggest and most important private collections of Australian aboriginal art are not owned by Australians.

Do you see a growth potential for Aboriginal art?

The Australian Aboriginal market is poised for growth. Last year, the annual auction turnover was still less than half of what it was at its peak of 26 million AUD in 2007. We have experienced new interest from Asian collectors, where in the past non-Australian collectors of Aboriginal work have predominately been from the United States and Western Europe. It will be interesting to look back at 2015–2016 in five years’ time… I think people will be amazed at the value.

Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Kame Colour XII (1996). Courtesy of Deutscher and Hackett.

artnet Auction House Partnerships offer an ideal way for auction houses to gain international exposure for their sales and lots. Learn more about becoming a partner here, or explore upcoming sales here.