The Back Room

The Back Room: Law and Order

This week, the uncertain limits of resale restrictions, South Korea blasts off, a shared-custody Kusama, and much more.

This week, the uncertain limits of resale restrictions, South Korea blasts off, a shared-custody Kusama, and much more.

Tim Schneider

Every Friday, Artnet News Pro members get exclusive access to the Back Room, our lively recap funneling only the week’s must-know intel into a nimble read you’ll actually enjoy.

This week in the Back Room: the uncertain limits of resale restrictions, South Korea blasts off, a shared-custody Kusama, and much more—all in a 7-minute read (2,077 words).

__________________________________________________________________________

X Museum founder and collector Michael Xufu Huang. Image courtesy X Museum.

Would a court uphold gallery-imposed restrictions on how and when a buyer can resell artworks? The answer has been debated for almost as long as modern art-market speculation has existed, partly because no U.S. or U.K. court has ever actually ruled on the matter before the litigants settled privately.

But it became a $1.325 million question last week, when Bloomberg broke the news of a lawsuit between X Museum founder Michael Xufu Huang and his former friend Federico Castro Debernardi.

In March 2021, Huang sued Debernardi, the Monaco-based founder of an Argentine art foundation, for allegedly breaching an agreement about a painting by the always-in-demand Cecily Brown. Documents show that Huang acquired the painting, titled Faeriefeller (2019), from Paula Cooper Gallery for $700,000 at Art Basel Miami Beach in 2019.

To do so, he had to sign a bill of sale with terms assuring the gallery that he…

What Paula Cooper didn’t know, documents submitted to the court show, was that Huang separately agreed to use his superior status as a museum founder to covertly acquire Faeriefeller for the less-known Debernardi in exchange for a 10 percent fee ($70,000), plus expenses ($5,000).

Other key terms of their pact included that…

The problem arose in August 2020, when Paula Cooper learned Faeriefeller was resold by Lévy Gorvy only four months after the date on Huang’s invoice. Cooper promptly threatened to sue Huang for breach of contract, for an amount between $500,000 and $1 million.

Huang told Bloomberg that he “took responsibility” and settled with Cooper for an amount “way over” his commission from Debernardi. (Sources with experience in similar cases hinted to me that the payment was likely around $300,000 based on the various fees and damages sought in Huang’s amended complaint.) Huang then sued Debernardi in March 2021.

The two parties settled privately only hours after Bloomberg published. Still, court filings in the case reinforce that the outcome in any conflict over resale covenants is likely to hinge as much on the economic and social relationships involved as it does on contract law.

Many secondary-market dealers, auction pros, and profit-minded buyers argue (to quote Debernardi’s counsel) that resale covenants are “unlawful tools of market manipulation.” But other art attorneys and industry pros have convinced me that an absolutist stance on either side of the issue is unwise. Details matter, and they differ in almost every dispute and every U.S. state.

So here are four questions useful in deciphering the merits of any particular case…

1. Are the Resale Restrictions Clearly Written and “Reasonable”?

It would be risky for a gallery to demand that buyers grant it, say, a lifetime right of first refusal, or an opportunity to buy back a work for less than the original sale price. But if a gallery stipulates, as Paula Cooper did for Faeriefeller, that its right of first refusal lasts only a few years and places no ceiling on secondary-market pricing, it stands a stronger chance of surviving a legal challenge.

This is especially true if ostensibly restrictive measures have long been used in the industry in question. So even though resale covenants in the art market have never been upheld in court, the pure fact that they have proliferated for decades makes them harder to bat down.

2. Does the Gallery That Imposed the Restrictions Also Have the Resources for Drawn-out Litigation?

The most depressing trait of the U.S. legal system is that the law often matters less than the amount of time and money you can afford to spend arguing about its meaning.

So a resale restriction imposed by a blue-chip gallery like Paula Cooper likely has more teeth than one imposed by the average smaller gallery, because the latter probably lacks the surplus cash, time, and energy needed to lawyer up for a protracted battle.

3. For the Health of the Gallery and Its Artists, How Replaceable Is the Buyer Who Misbehaved?

Threatening to sue a collector is the nuclear option; it means the gallery has no fear of a future without that client relationship, partly because the all-but-guaranteed bad press from the lawsuit can stain a perceived flipper forever.

It’s a simple decision if the offender has no prior art world standing. It’s much more complicated if their alleged malfeasance has to be weighed against their trusteeship in a major institution, their founding of a private museum, or even just their long track record of acquiring works by artists that went on to have tremendous careers. Even more so if a gallery’s collector pool has few, if any, patrons of similar caliber eager for the same inventory.

4. Are Back-channel Resolutions Amenable?

Although galleries have long been known to blacklist resale violators, other forms of compensation sometimes come into play too, especially if a lusted-after work reaches auction early.

To avoid having to withdraw a piece over a legal challenge, sources say, houses have been known to convince consignors to funnel a percentage of the sales proceeds to the gallery, and/or to hand the gallery a portion of the buyer’s premium.

In rare cases, the house might even offer to give the gallery a paddle and, if the gallery wins the lot, sell it to them at the underbidder’s price… though, in practice, this last one may just be a poison pill intended to get the gallery to stand down.

__________________________________________________________________________

The art world has repeatedly shown that it can and will police resale restrictions internally by whatever means are within its power and appropriate to the circumstances. That doesn’t mean we won’t see more lawsuits like the one between Huang and Debernardi. But it does mean that we’re still unlikely to get a court ruling on this long-simmering uncertainty anytime soon.

____________________________________________________________________________

Wet Paint will be up later today, but here’s what else made a mark around the industry since last Friday morning…

Art Fairs

Auction Houses

Galleries

Institutions

NFTs and More

____________________________________________________________________________

© 2022 Artnet Price Database and Artnet Analytics.

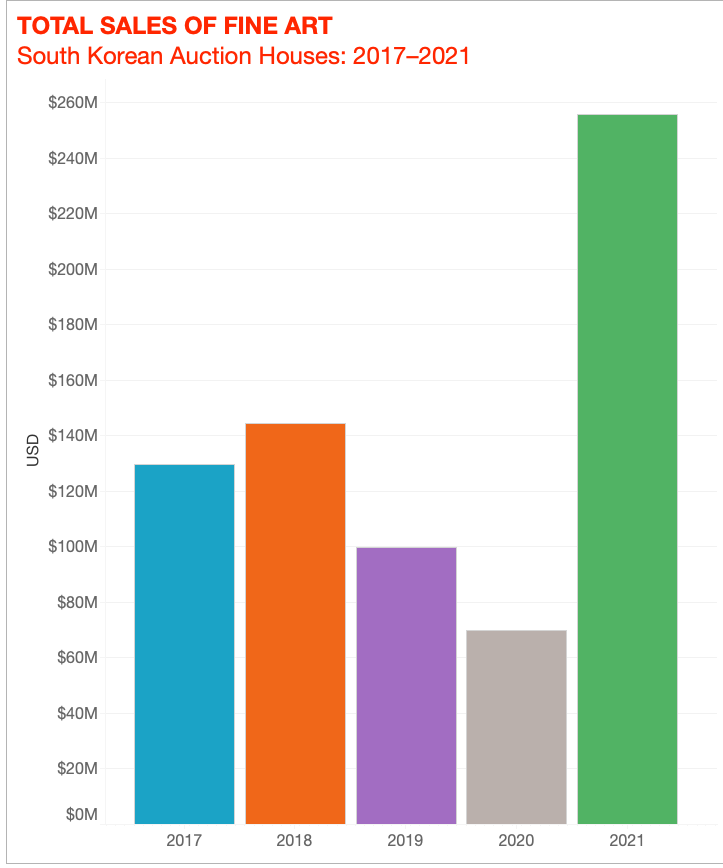

Combined with a growing slew of expansions by international galleries and the looming debut of Frieze Seoul this September, the latest auction data reinforces that South Korea entered 2022 as the fastest-rising regional art market on earth.

For more insights into the country’s catapulting art market, click through below.

____________________________________________________________________________

“Everyone was, like, ‘Oh, you’re making so much money, you must be so happy’ … Nobody at Art Blocks enjoyed August. It was awful. It felt like we were getting trampled by speculation.”

—Erick Calderon, founder of the generative NFT platform Art Blocks, explaining why he created a board to curate all future works offered on the exchange, new auction mechanisms to disincentivize flippers, and a physical gallery in the art-world haven of Marfa last fall. (New Yorker)

____________________________________________________________________________

Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirrored Room – My Heart Is Dancing Into the Universe (2018). Photo: Jack Hems. Courtesy Ota Fine Arts and Victoria Miro, London/Venice. © YAYOI KUSAMA. Purchased jointly by the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. (Joseph H. Hirshhorn Purchase Fund, 2020), and the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, with funds from the George B. and Jenny R. Mathews Fund, by exchange.

____________________________________________________________________________

Acquired by: The Albright-Knox Art Gallery and the Hirshhorn

Sold via: Private Transaction

As public institutions try to compete against private mega-collectors in our new Gilded Age, joint museum acquisitions are becoming more and more common. The latest example was announced this week, when the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York teamed up with the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden to nab this recent Yayoi Kusama crowd pleaser.

Infinity Mirrored Room—My Heart Is Dancing Into the Universe first appeared in Victoria Miro’s ticketed 2018 Kusama solo show, “THE MOVING MOMENT WHEN I WENT TO THE UNIVERSE.” It houses an array of color-changing paper lanterns emblazoned with the artist’s telltale polka dots, transforming the interior into a psychedelic wonderland.

The joint acquisition continues both museums’ commitments to immersive art and Kusama herself. The Hirshhorn will install the work first, in tandem with its spring 2022 exhibition “One with Eternity: Yayoi Kusama in the Hirshhorn Collection.” The Albright-Knox, which owns her first-ever Infinity Mirrored Room (subtitled Phalli’s Field) from 1965/2017, will assume custody after its ambitious campus-expansion project comes to an end in 2023. (The institution will be rechristened the Buffalo AKG Art Museum at that point.)

Expect a barrage of selfies to blast out of each location when the time comes. Of the six institutions that hosted the traveling exhibition “Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors” a few years back, four enjoyed seasonal attendance figures that were “among the highest in the institutions’ histories,” according to a spokesperson. So no matter how finished you might be with immersive art on a personal level, immersive art isn’t finished with you.

____________________________________________________________________________

Additional contributions by Naomi Rea.