The Back Room

The Back Room: Mass Movement

This week: NFTs try to break big, Robert Indiana's auction troubles, Lynne Drexler goes supersonic, and much more.

This week: NFTs try to break big, Robert Indiana's auction troubles, Lynne Drexler goes supersonic, and much more.

Tim Schneider

Every Friday, Artnet News Pro members get exclusive access to the Back Room, our lively recap funneling only the week’s must-know intel into a nimble read you’ll actually enjoy.

This week in the Back Room: NFTs try to break big, Robert Indiana’s auction troubles, Lynne Drexler goes supersonic, and much more—all in an 8-minute read (2,175 words).

__________________________________________________________________________

A scrap dealer in India pushes his handcart past NFT graffiti. (Photo by Ashish Vaishnav/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images)

Consolidation isn’t just for the traditional art business anymore.

Last Friday, Yuga Labs, the company that spawned the wildly expensive Bored Ape Yacht Club NFT series, announced that it had acquired the intellectual property behind rival Larva Labs’ CryptoPunks and Meebits projects. The deal brings three of the top-selling crypto franchises under one blockchain-supported roof.

But a curious wrinkle in the pact attempts a novel solution to a riddle facing more and more art professionals in this era of Instagram-ready immersive installations, branded merchandise, and fractionalized ownership: How do you turn a niche obsession into a mainstream phenomenon?

Yuga Labs’ answer is to grant direct financial incentives to NFT owners to help the company build—and market—a creative universe around its tentpole intellectual property (I.P.).

Today, I want to walk through this unorthodox strategy, and explain why it may serve as a cautionary tale for an art trade increasingly thirsty to go mainstream.

Although the company will maintain control of the underlying brands and logos for both series, it will transfer the I.P., commercial, and exclusive licensing rights for each individual CryptoPunks and Meebits NFT to its respective holder. The move empowers the NFT owners to legally proliferate, and profit from, derivative works based on the tokenized character.

In other words, Yuga Labs will still own the overarching CryptoPunks and Meebits worlds, allowing them to expand on the concepts with new characters and ideas. But the company will cede control of the individual characters to whoever acquired the corresponding NFTs.

Yuga Labs embedded these incentives in the Bored Ape Yacht Club NFTs from day one. But there is nothing else quite like it outside the crypto space, let alone inside the art market.

The best hypothetical I can offer would be if Takashi Murakami had announced early in his career that he would transfer the underlying rights for each of his different characters—Mr. DoB, Kaikai and Kiki, Miss Ko2, etc.—to whoever owned the first painting or sculpture in which it appeared.

Instead of Murakami himself being the one to produce and monetize any subsequent uses of those characters, then, the rights to do those things would convey to the individual collectors holding the unique source material.

The arrangement would empower the buyers to license out “their” character’s image as is, or make it the basis of some number of derivative products or vehicles (toys, clothing lines, video games, animated series, whatever), with full legal protection and rights to the net profits.

My read is that the company’s ambitions are much larger than the audience its NFTs alone can wrangle. There are only 10,000 Bored Ape NFTs, another 10,000 CryptoPunk NFTs, and 20,000 Meebits NFTs.

In some cases, hundreds or even thousands of the tokens from each series are owned by the same individuals or consortiums. Yuga Labs itself received 423 CryptoPunks and 1,711 Meebits from the personal stash of Larva Labs’ cofounders as part of the I.P. deal.

Each NFT is expensive, too. The cheapest Meebit now costs around 5.6 ETH ($14,500). The floor price for a CryptoPunk is around 75 ETH ($195,000). Bored Apes sell for at least 97 ETH ($250,000).

How do you build a broad fanbase for I.P. in such short supply, and with such fat price tags? One answer is to create derivative works available at low costs. Think of the Basquiat estate licensing the artist’s imagery for Uniqlo t-shirts.

The difference is that Yuga Labs is outsourcing this task to NFT owners rather than proliferating the Punks, Meebits, and Apes in house.

As Amy Castor noted in a feature on the company’s widescreen goals, the world has already been introduced to “a Bored Ape IPA,” BAYC-branded weed, and at least one NFT offshoot.

Last year, Universal Music Group signed a Bored Ape “supergroup” (called Kingship) to release music and perform in the metaverse, and pop/hip hop producer Timbaland announced Ape-In Productions, which will also put out music and sell its related NFTs.

On Wednesday, I also learned about Bored and Hungry, “the world’s first restaurant based on a Bored Ape.” The pop-up burger joint will run for 90 days in Long Beach, California, but “could be the first of multiple locations,” per a company statement.

All of the above should give us a sense of what to expect from Punks and Meebits owners soon.

It’s hard to say, but attempts to financially incentivize fan-produced works have a checkered history.

Professor Anne Jamison, the lead author of the collection Fic: Why Fanfiction Is Taking Over the World, said that Yuga Labs’s plan reminded her of Amazon’s now-defunct Kindle Worlds. An arm of the retail giant’s Kindle Direct Publishing service, Kindle Worlds sold only fanfiction blessed by the original rightsholders, who took 35 percent of sales.

Jamison considered the profit motive antithetical to true fanworks, which normally thrive on a community ethos that is inherently not for profit. Amazon shut down Kindle Worlds in 2018, with no real specifics as to why. But given Jeff Bezos’s interest in money over pretty much everything else, I know which explanation I’d bet on.

__________________________________________________________________________

By incentivizing early adopters to become mini-entrepreneurs for its own good, Yuga Labs’ strategy sounds less like it’s aimed at building a mass movement of genuine fans than at building a multilevel marketing business. Instead of Disney, the more appropriate comps in my eyes would be Amway, Herbalife, and Mary Kay cosmetics.

However, since Yuga Labs still owns the overarching brands, the company is still principally responsible for building worlds and narratives that can magnetize the masses to the CryptoPunks, Meebits, and Bored Apes. That may be all that matters. In fact, I think it will have to be. Because paid evangelism tends to have a much harder time proliferating beyond the clubhouse—a lesson the art world should keep in mind, too.

____________________________________________________________________________

Views of the State Hermitage Museum and Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, Russia. Photo: by Julian Finney/Getty Images.

Our Wet Paint scribe is off this week, but here’s what made a mark around the industry since last Friday morning…

Russia-Ukraine Fallout

London’s National Gallery canceled its request to borrow a Raphael from the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, while the Louvre, Versailles, and the U.K.’s Royal Collection pulled their loans from a forthcoming show on dueling at the Kremlin Museum. (The Art Newspaper / ARTnews)

Art Fairs

Auction Houses

Galleries

Institutions

NFTs and More

____________________________________________________________________________

© 2022 Artnet Worldwide Corporation.

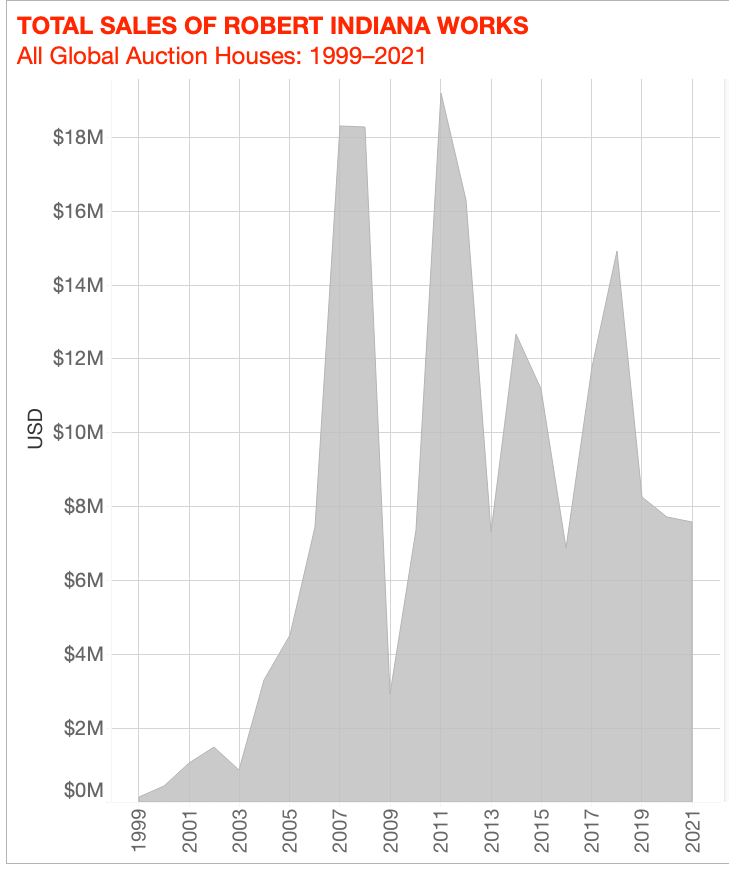

The work of deceased American Pop art icon Robert Indiana is now on view in the artist’s first major U.K. survey, at Yorkshire Sculpture Park. Can the ambitious show help counteract a multiyear auction slide synced with the seemingly never-ending legal fracas over his estate?

For more details, click through for the latest Artnet News Pro Appraisal.

____________________________________________________________________________

“We basically advise our clients to think of sanctioned parties as functionally dead to the world. And when in doubt, we tell clients not to proceed. The risks of running afoul of the constantly changing regulations in this area just aren’t worth it.”

—Attorneys Thomas Danziger and Joan Gmora, offering food for thought regarding individuals sanctioned in the international response to the Russian invasion. (Artnet News)

____________________________________________________________________________

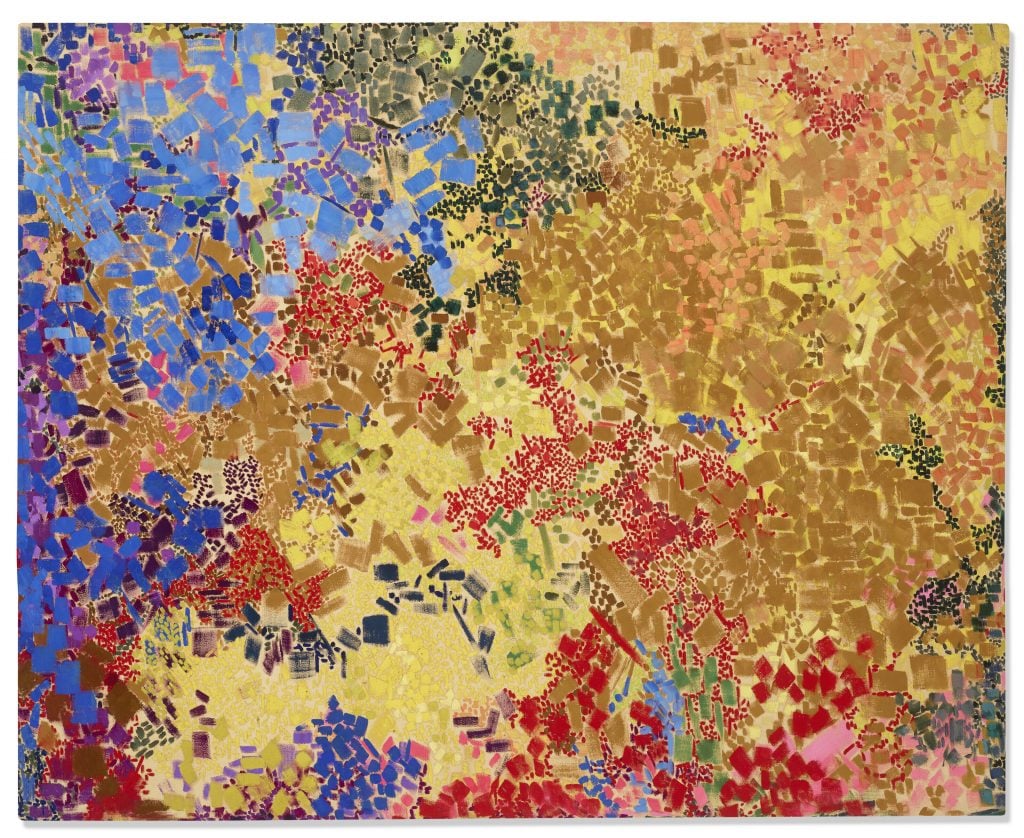

Lynne Drexler, Flowered Hundred (1962). Courtesy of Christie’s.

____________________________________________________________________________

Estimate: $40,000 to $60,000

Sale Price: $1.2 million

Sold at: Christie’s (NY) Postwar to the Present

A market primed for rediscoveries may have found its next obsession: Lynne Drexler, a Virginia-born colorist whose dissatisfaction with New York art-scene politics drove her to live out the final 16 years of her life on a remote Maine island, often selling paintings to tourists.

A student of both Hans Hofmann and Robert Motherwell, Drexler had early shows at the vaunted Tanager Gallery, alongside Alex Katz, Philip Guston, Robert Rauschenberg, and other now-canonical talents. But she felt that the patriarchy sidelined her over time, eventually spurring her to permanently move to Monhegan Island, a combination fishing haven and artist’s colony, in 1983.

Only 16 Drexler works have reached the auction block to date, according to the Artnet Price Database. All but one have been offered in the past five years, and all but three via regional auctioneers.

The first lot to perk up eyebrows among the upper echelon came last May, when a roughly two-foot-by-two-foot painting, titled Daffodil Gloucester (1960), soared to $75,000 against a $12,000 high estimate in the postwar and contemporary day sale at Christie’s New York. One Drexler collector said that prices have reached into the six figures on the private market.

No other pieces by the artist came up at a major house until last week, when Flowered Hundred unexpectedly blasted through the million-dollar mark. Julian Ehrlich, head of Christie’s Postwar to Present sale, called it the first Drexler painting “of its size, date, and quality” to appear under the hammer. (Keller Fair, a tiny painting dated ca. 1959, went for $69,300—more than quadruple its high expectation—in the same sale.)

Drexler’s estate gifted Flowered Hundred to Rockland, Maine’s Farnsworth Art Museum in 2002. The sales proceeds will replenish the acquisition fund. Here’s hoping the museum still has all the Drexler paintings it wants, because it might just have helped price itself out of the market otherwise.

____________________________________________________________________________

With contributions by Naomi Rea.