Before Kehinde Wiley patented his slick likenesses of black aristocracy or Titus Kaphar foisted painted images of Ferguson protesters onto the cover of Time Magazine, there was Barkley L. Hendricks—the originator of painting’s cool school. Scoping out his wide-ranging influence, it seems inconceivable that this pioneer of Pop-inflected portraiture ever worked in obscurity. A terrific exhibition of new paintings at Jack Shainman Gallery in New York serves as a reminder of why Hendricks remains, for contemporary painting and painters, the undisputed godfather of soul.

The tag “The Birth of the Cool” was originally coined to baptize Miles Davis’s 1950s sound. But the phrase fit Hendricks’ timeless paintings so naturally that, in 2008, it titled the artist’s only survey to date. The exhibition, organized by current Nasher Museum of Art Chief Curator Trevor Schoonmaker, was a traveling revelation for those not yet acquainted with Hendricks’ achievements (I caught the show, like an epiphany, at the Santa Monica Museum of Art). In the words of LA Times critic Christopher Knight, “Hendricks explored the intersection of the black experience and painting history.” Most important, Hendricks’ multi-museum exhibition delivered an artistic tour de force that appeared to emerge, full-blown, from within America’s racially wounded psyche.

Barkley L. Hendricks. 524 West 24th Street.

Photo: Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

If the key experience for the young 23-year-old Hendricks, circa 1968, was a grand tour of European museums—it mixed direct lessons in Old Master paintings with first-person schooling on the black figure’s historical invisibility—the 70-year-old artist has lately become a leading portraitist of Obama-era America. Where his figures once chronicled the defiant stylings of 1970s blackness, today they occupy a far more central place—much like black culture does in the national discourse. Now as then, Hendricks’ canvases galvanize whole fields of visual stimuli that include sports, politics, music, fashion, and, of course, painting. His iconic portraits—nine of which grace Jack Shainman’s West 24th Street space—plug modern ways of seeing into thousands of years of art history, revealing correspondences, incongruities and, as often as not, yawning gaps.

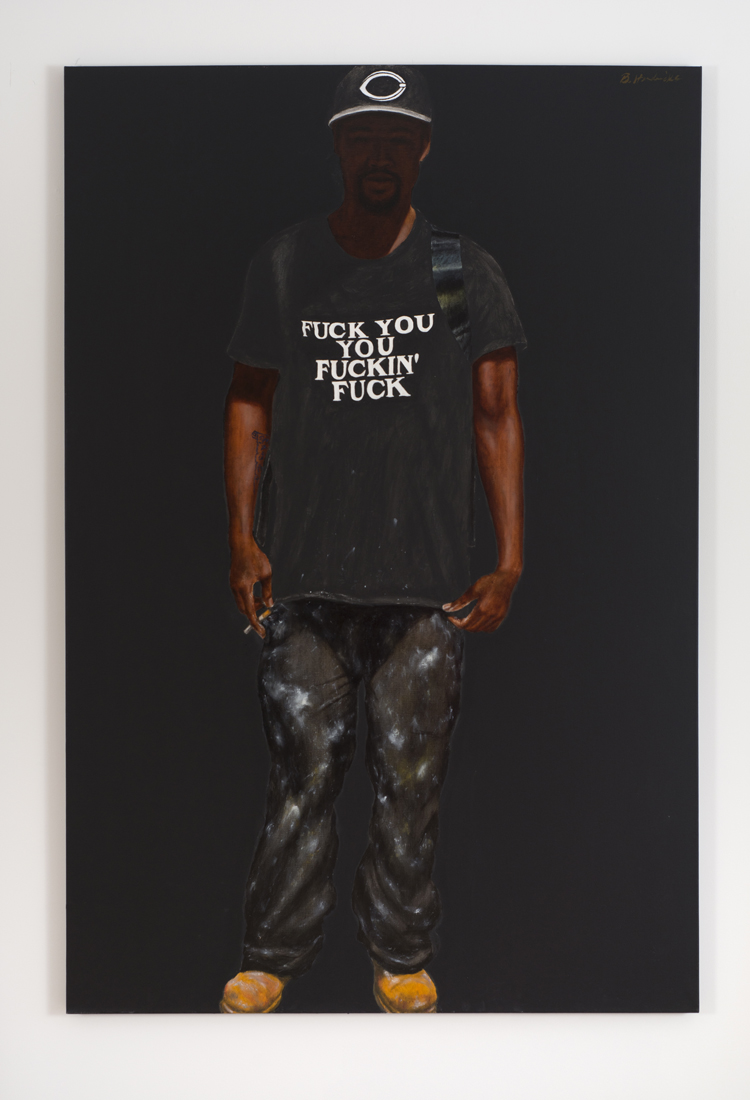

Barkley L. Hendricks, Manhattan Memo (2015).

Photo: Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Though all of Hendricks’ latest oil and acrylic on canvas works jibe with the most prominent paintings in his oeuvre—he is best known for realistic portraits of fashionable black people against flat, single-color backgrounds—several take a hard turn toward the political, echoing slogans from newspaper headlines and the Black Lives Matter movement. This development is, to say the least, uncharacteristic in an artist who much prefers entertaining eccentric figure and ground arrangements to espousing overt social commentary. (If you don’t believe me, see Hendricks’ contentious March interview with Karen Rosenberg at Artspace.)

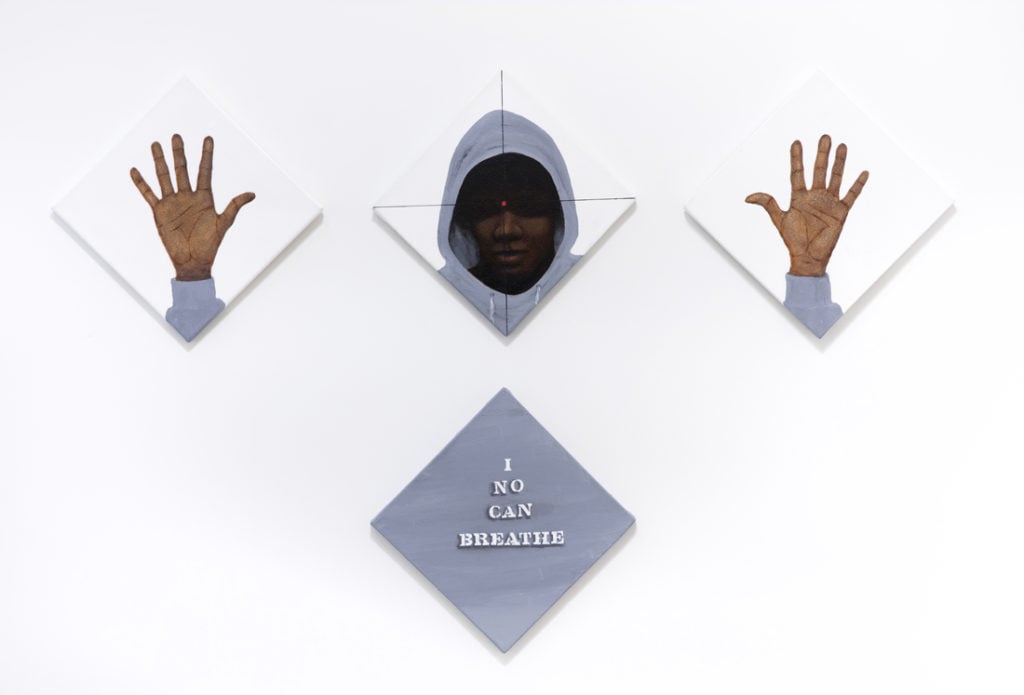

But whatever Hendricks’ past preferences, there’s no avoiding his current views on American politics at Shainman. Among other works, the paintings Crosshairs Study and In the Crosshairs of the States—both of which consist of multiple canvases—feature a young man in a hooded sweatshirt with upraised hands whom the artist places squarely in a gun’s sights. If the image appears crude or unusually straightforward, consider Manet’s three versions of Emperor Maximilian’s execution—pictures that also used deadpan depiction to describe a very public martyrdom. The largest of Hendricks’ two Trayvon Martin-as-Jesus pictures uses the confederate battle flag as background; his grayscale “study” includes a stenciled adaptation of Eric Garner’s last words: “I No Can Breathe.”

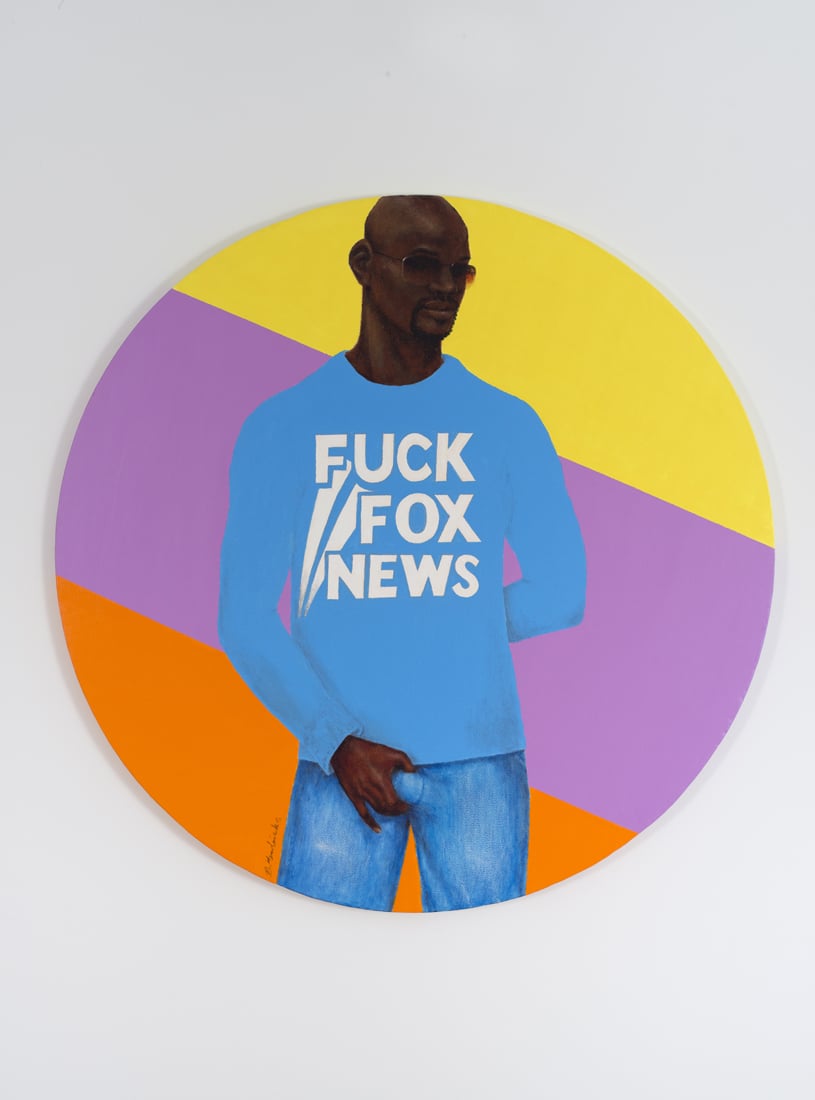

Barkley L. Hendricks, Roscoe (2016).

Photo: Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

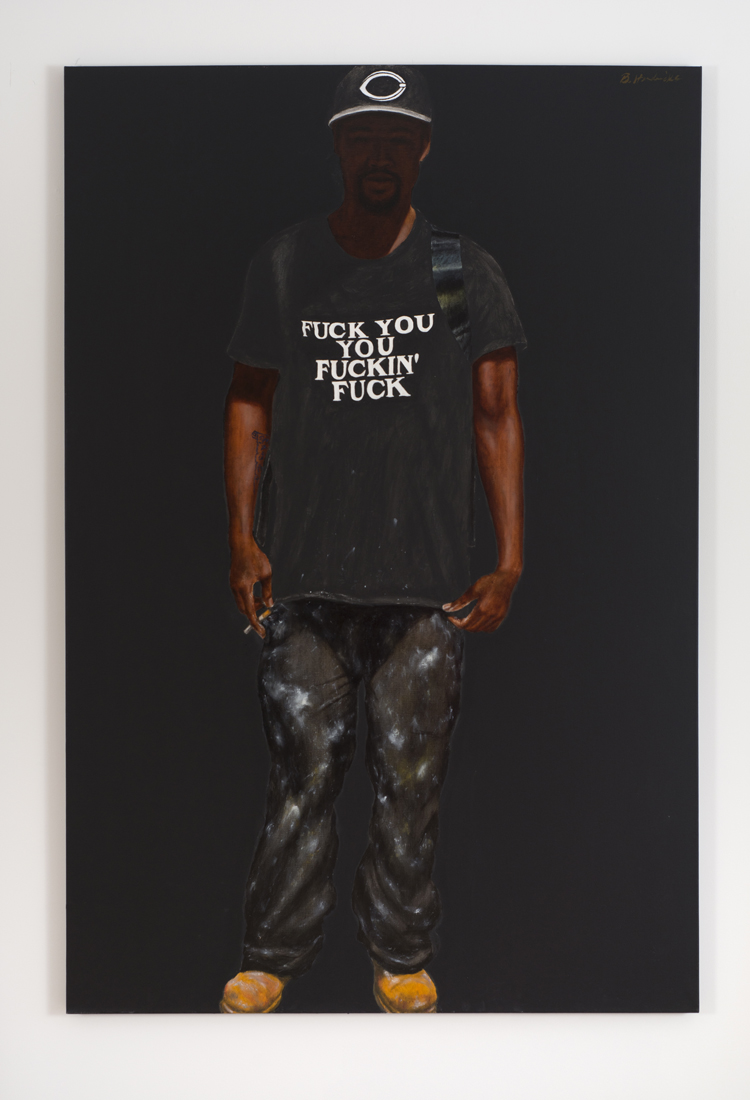

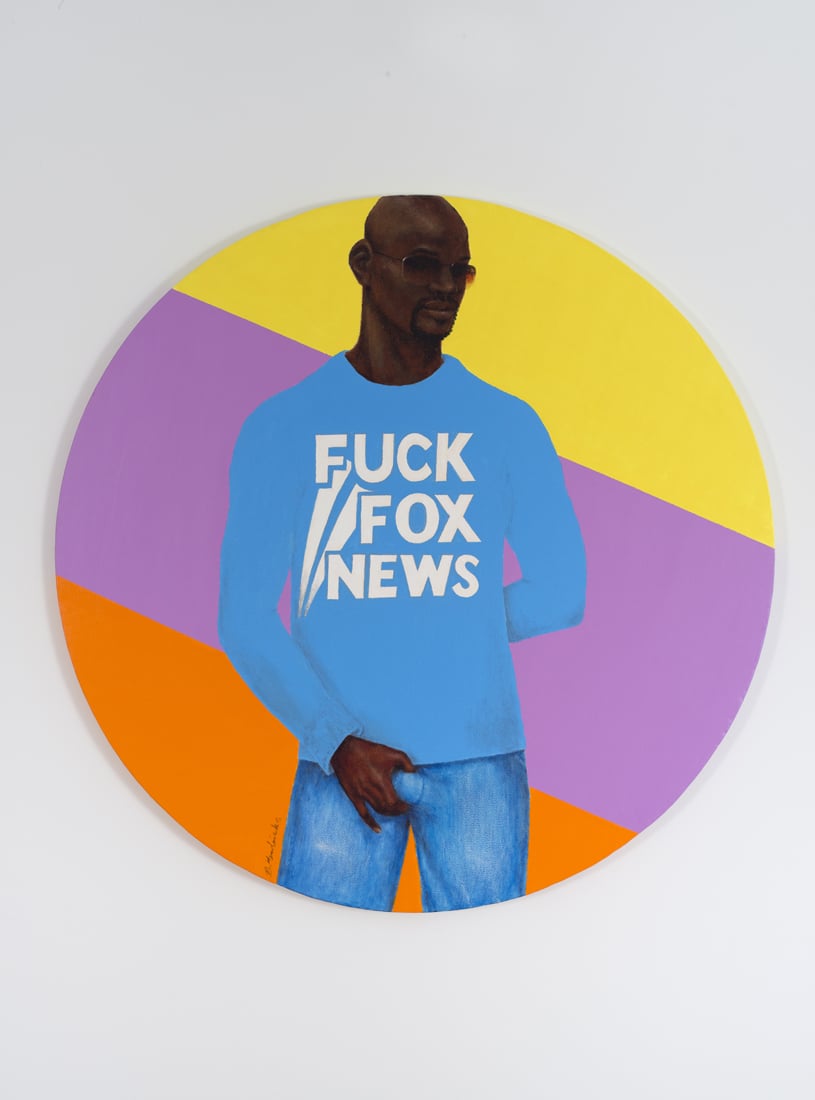

Other Hendricks’ portraits also wear their own politics openly, but do so characteristically on their chest. There’s Roscoe, a large circular canvas featuring a rainbow background with a centrally located player in jeans, shades, and a blue t-shirt that bluntly reads “Fuck Fox News.” And then there is Manhattan Memo, a full-length portrait of a black man in Timberlands, paint-flecked jeans, a baseball cap, and dark t-shirt; it’s slogan repeats the legendary f-bomb cluster from Spike Lee’s 2002 film 25th Hour: “Fuck You You Fucking Fuck.” Despite the harshness of the expression, Whistler or Bronzino unavoidably come to mind. Like Hendricks, both precursors were expert at projecting their subjects’ aristocratic bearing—what we call “coolness” today.

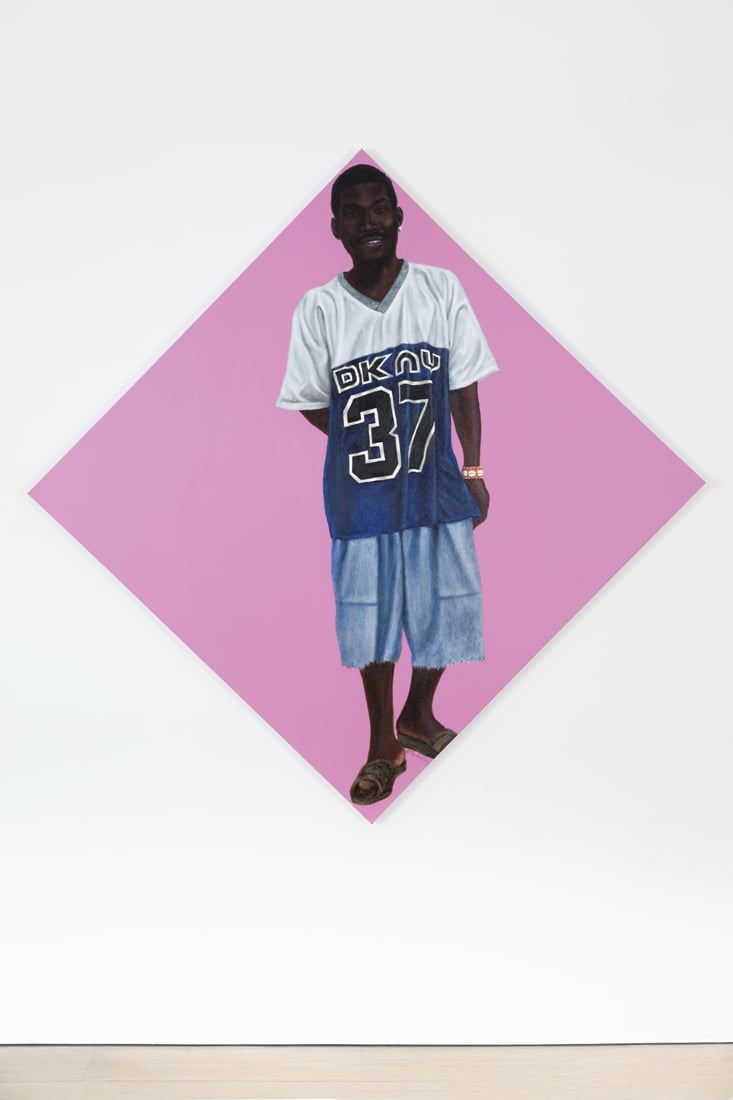

Barkley L. Hendricks, JohnWayne (2015).

Photo: Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

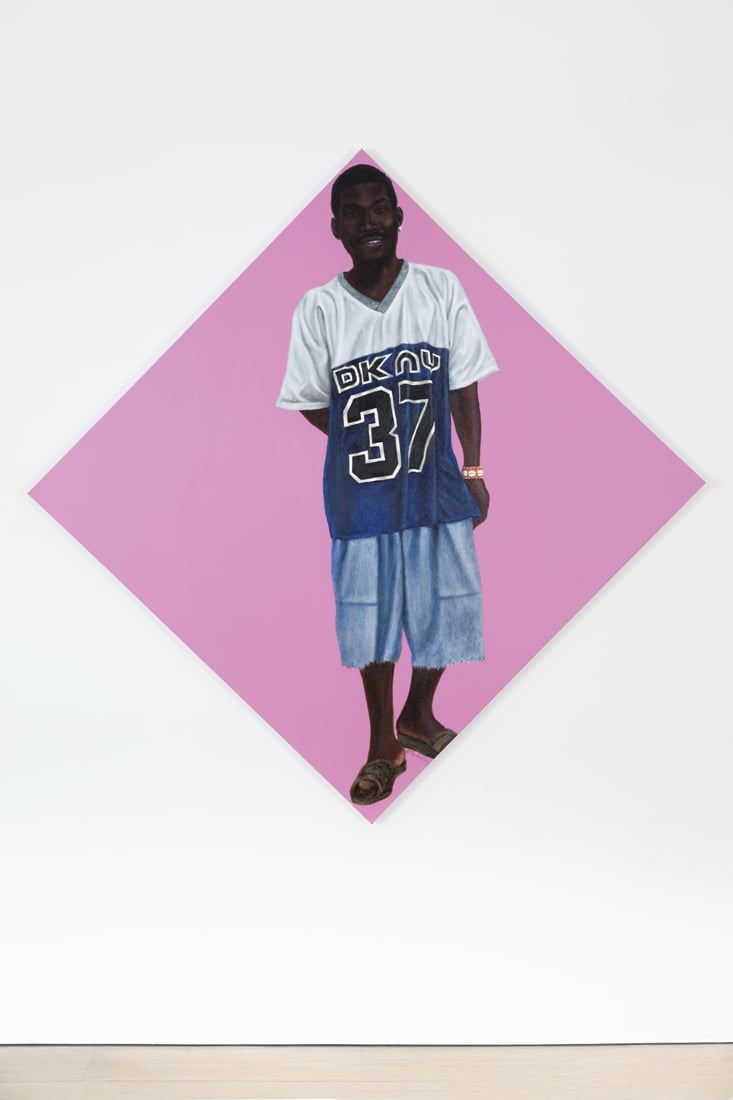

But not everything reads political in Hendricks’ new show; conversely, those paintings that propound politics are never reducible to mere slogans. Take, for instance, the square and rectangular canvases the artist turns on their axes to suggest movement or instability. In keeping with this minor innovation, the paintings Anthem and Passion Dancehall use their frames’ tilt to underscore the energy of their dancing, singing and partying subjects. A third portrait, featuring a spindly Chris Rock look-alike Hendricks has ironically titled John Wayne, uses the diamond format of its hand-made frame to echo the bling its subject gleefully sports on his left ear.

Barkley L. Hendricks. 524 West 24th Street.

Photo: Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Ultimately what animates Hendricks’ paintings is an eye for the public impostures that attire private selves, with a specialty in the attitudes inflamed by America’s ongoing racial dilemma and, by extension, the insecurities attendant to stubborn power dynamics. Oscar Wilde, a dandy like Hendricks and most of his portrait subjects, once said the following about the art of painting people’s likenesses: “Every portrait that is painted with feeling is a portrait of the artist, not of the sitter.” In Hendricks’ case his portraits are also frank, unsparing glimpses into the American-born, globalized, self-expressive phenomena called soul.

“Barkley L. Hendricks” is on view at Jack Shainman Gallery in New York from March 17-April 23, 2016.