The Art Detective

A Mysterious Brice Marden Painting Is Auction-Bound, and the Art Detective Is on the Case

Unknown to experts, the canvas could soon sell for a record $50 million. Who has consigned it?

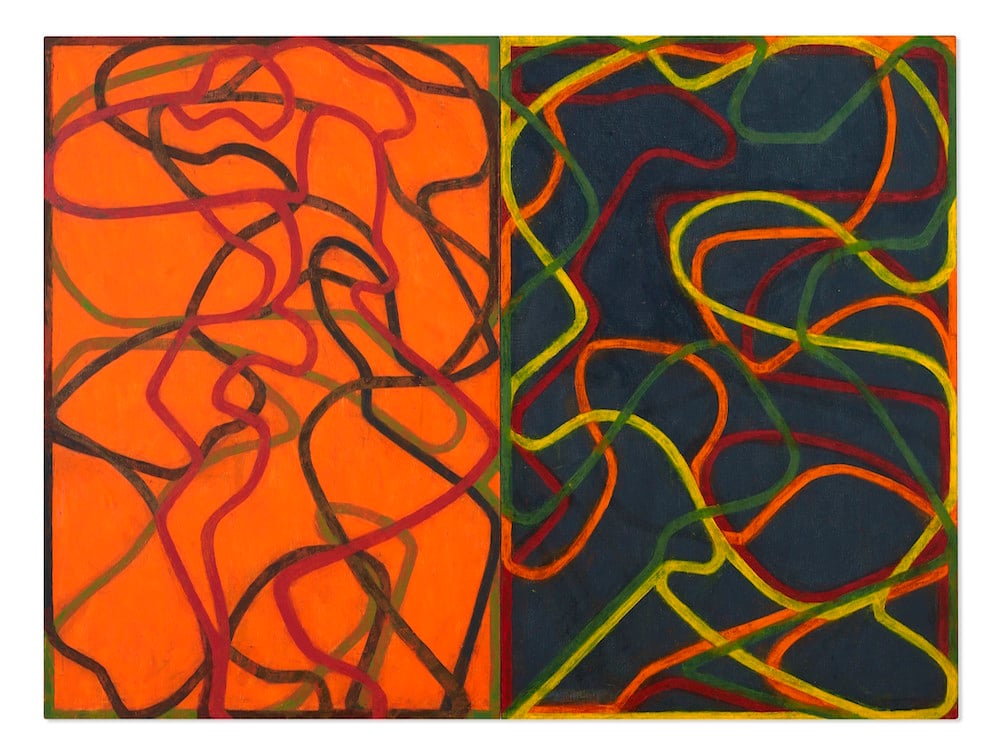

Last week, Christie’s announced a big get for the bellwether May auction season in New York: a gorgeous diptych by Brice Marden, which it estimated at $30 million to $50 million.

Titled Event (2004–07), the painting is poised to set a new auction record for the revered abstract artist, who died last year at 84. Both the canvas and its seller are a mystery. The work has never been exhibited, and its very existence has surprised some of the ultimate Marden experts. The consignor is anonymous.

Full disclosure: I have a soft spot for Marden. His spellbinding retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in 2006 coincided with my start on the art-market beat. He continued to turn out lyrical and rigorous canvases until his final days. Every new exhibition was a revelation.

And now Event, with its ribbons of color dancing on fields of green and yellow, may cement Marden’s place in the most rarefied sphere of the art market. Of the more than 415,000 artists tracked by the Artnet Price Database, just 98 have had a work surpass $30 million at auction and only 51 have had one exceed $50 million.

New paintings by Marden have been notoriously hard to get. So, I wondered: Who was the collector lucky enough to score this one? It had to be someone well-connected and wealthy—another collector paid $3 million for a sister painting (more on that later). It also had to be a shrewd negotiator: the consignor got Christie’s to guarantee the work, ensuring a windfall no matter what actually happens at auction.

It was an intriguing riddle to solve. And the answer surprised me.

But allow me to back up. Event is one of six works in Marden’s ambitious “The Propitious Garden of Plane Image” series. The group consists of two monumental, six-panel paintings (Second Version and Third Version), one smaller sequence (First Version), and three diptychs (Event, Complements, and Extremes). Apart from First Version, each panel in the series has the same dimensions: 6 feet tall and 4 feet wide. At least two are in major museum collections.

Brice Marden, Complements (2004-2007). Image courtesy Christie’s

Complements (2004–07) used to belong to financier Don Marron, who was the chairman of Lightyear Capital and a longtime MoMA trustee.

Marron died in December 2019, and the highlights of his collection were famously sold by a troika of powerful galleries—Gagosian, Acquavella, and Pace—who joined forces to outbid the auction houses. Paintings by Mark Rothko, Pablo Picasso, and Mark Bradford all found buyers right away, and not a moment too soon. Within weeks, the pandemic had shut down the world.

One work that didn’t immediately find a buyer was Complements. Several months later, it appeared at Christie’s first major live-streamed auction with a huge estimate: $28 million to $35 million. Until then, Marden’s auction record was $16.9 million.

Bidding was minimal and the work ended up being bought by the third-party guarantor for $30.9 million (including fees). That record price appears to be the basis for Event’s current estimate.

There’s an interesting side story here. Marron was coveting a significant Marden painting in the early aughts. But so were other major New York collectors, and Matthew Marks Gallery, which represented the artist at the time, stringently guarded access to his new works.

The gallery told Marron that he would get the first pick from the “Propitious Garden” series on the condition that he bought another major work for MoMA. (Yes, people, the curse of BOGO—or “buy one, give one”—deals are not a new phenomenon.)

Brice Marden prior to his death in 2023. Photo courtesy of Gagosian.

And so, in 2006, Marron bought one of the two six-panel paintings, Third Version, for the museum. It was a last-minute addition to the Gary Garrels-curated retrospective—a thrilling coda to more than four decades of painting. Its paint was still wet.

Shortly before the show opened, Marron drove up to Marden’s studio in Tivoli, New York, to select a painting for his personal collection.

“There were two paintings in front of us,” Matthew Armstrong, a former curator of Lightyear Capital, said this week.

Marron chose Complements, with calligraphic rivulets of color on dark blue and orange backgrounds and paid $3 million for it. The second diptych, Extremes (2004–05) would enter the collection of the Centre Pompidou in Paris as a gift of the Clarence Westbury Foundation in 2006, according to the museum’s website.

Armstrong said he didn’t know that a third diptych existed. Neither did Garrels.

“I alas know nothing about this painting,” Garrels said in an email. “Brice finished it after the retrospective that I curated. I very much will look forward to seeing this painting at Christie’s as I have never seen it before.”

I was surprised that Event was sold by Thomas Ammann gallery in Switzerland, as Christie’s states in its provenance, and not by Matthew Marks. But those who knew the artist pointed out that Doris Ammann, the gallery’s late co-founder, was Marden’s friend, patron, and dealer in Europe.

The second surprise was who ended up getting the trophy diptych. It wasn’t, for example, the Daros Foundation, which had close ties to the gallery. Or the Clarence Westbury Foundation. Or the artist’s wife Helen Marden, long thought to have the first choice on new paintings, before any powerful dealer or collector.

Brice Marden with an early work. Photo courtesy of Gagosian.

Instead, Ammann sold the coveted diptych to the reclusive British collector Richard Schlagman, according to a person familiar with the work.

The name didn’t ring a bell, and he appears to have a minimal digital footprint. So, I asked around. It turns out that Schlagman was at one point a trustee of the Judd Foundation and helped orchestrate the its famous auction of some of its Donald Judd holdings at Christie’s in 2006. He was also the owner of the art publisher Phaidon Press, which he acquired in 1990 and sold to Leon Black in 2012.

Schlagman also had personal and business ties to Thomas Ammann Gallery. In 2002, Phaidon published the first volume of Andy Warhol’s catalogue raisonné, a massive undertaking initiated by Thomas Ammann, Doris’s brother who died in 1993. (Six volumes have been published to date.) The first two volumes were co-written by Georg Frei, who was Doris Ammann’s “collaborator and soulmate,” dealer Larry Gagosian wrote, following her death in 2021.

Several people who knew Schlagman said that Minimalist art was his first love, and that he bought a stunning villa designed by Marcel Breuer in Switzerland.

I wasn’t able to reach the elusive collector for comment or determine what hoops he had to jump through (if any) to obtain Event. Christie’s declined to comment on the consignor’s identity. Matthew Marks gallery didn’t respond to a request for comment.

This is one of many tales in the art world about access, and money, and great paintings. But it reminded me of something essential: Human connection is a currency that can still trump buckets of cash. Masters of the universe do not necessarily always get the best deal.