Art Collectors

Dameon and Kimberly Fisher Pour Their Hearts Into Being ‘Cultural Caretakers’ for the Work of Southern Black Artists

The Atlanta-based collectors want to share their vast trove of works by Black Southern artists with the world.

The Atlanta-based collectors want to share their vast trove of works by Black Southern artists with the world.

Melissa Smith

When Atlanta-based collectors Dameon and Kimberly Fisher met Russell L. Goings, former chairman of the Studio Museum in Harlem and a renowned collector of works by Romare Bearden, they thought at first he was sizing them up. “So, you call yourself collectors, huh?” Goings asked them.

“Uh, yes,” they remember replying.

“No,” Goings quickly clarified. “You guys are cultural caretakers.”

Taking this role seriously, the Fishers have built, particularly over the last 10 years, a robust collection of more than 250 works by Black artists, mainly from the American South. The region’s rich cultural history remains narrowly defined by the art world, effectively leaving out a big part of the American Black experience at a time when we’re in the midst of what some are calling a “reverse Great Migration,” with many Black people moving back.

Seeing it as their responsibility to be the emissaries of that experience—and to responsibly introduce “these artists to the world,” as Dameon, an orthodontist, likes to say—the Fishers seize opportunities to bring more attention to Black Southern artists. (They recently introduced the actor Samuel L. Jackson to Alfred Conteh, an Atlanta-based multidisciplinary artist represented in their collection.)

Attracted to pieces that illustrate Black culture’s beauty and resilience, the Fishers have branched out to include work by artists from other parts of the country, like Deborah Roberts and Kehinde Wiley.

Kevin Cole, When Preparation Meets Opportunity (2017). Courtesy of Dameon and Kimberly Fisher.

Establishing a broad visual language for Black art making requires support—particularly for Black artists who have little connection to the New York art scene. To help provide it, the Fishers plan to convert their second home, in northern Georgia, into a residency for local talent. For them, “it’s not so much ownership for the sake of ownership,” said Juan Logan, an abstract painter represented in the Fishers’ collection.

The seasoned Atlanta-based artist Kevin Cole—whose work the Fishers appreciate for its deft use of the image of neckties as a symbol of Black struggle, striving, and success—is already considering how to preserve their collection. He’s helping the couple cultivate relationships with local art institutions like the Tubman Museum, in Macon, Georgia. The Fishers are also eyeing their alma mater, Clark Atlanta University, an HBCU, as a potential beneficiary of part of their collection.

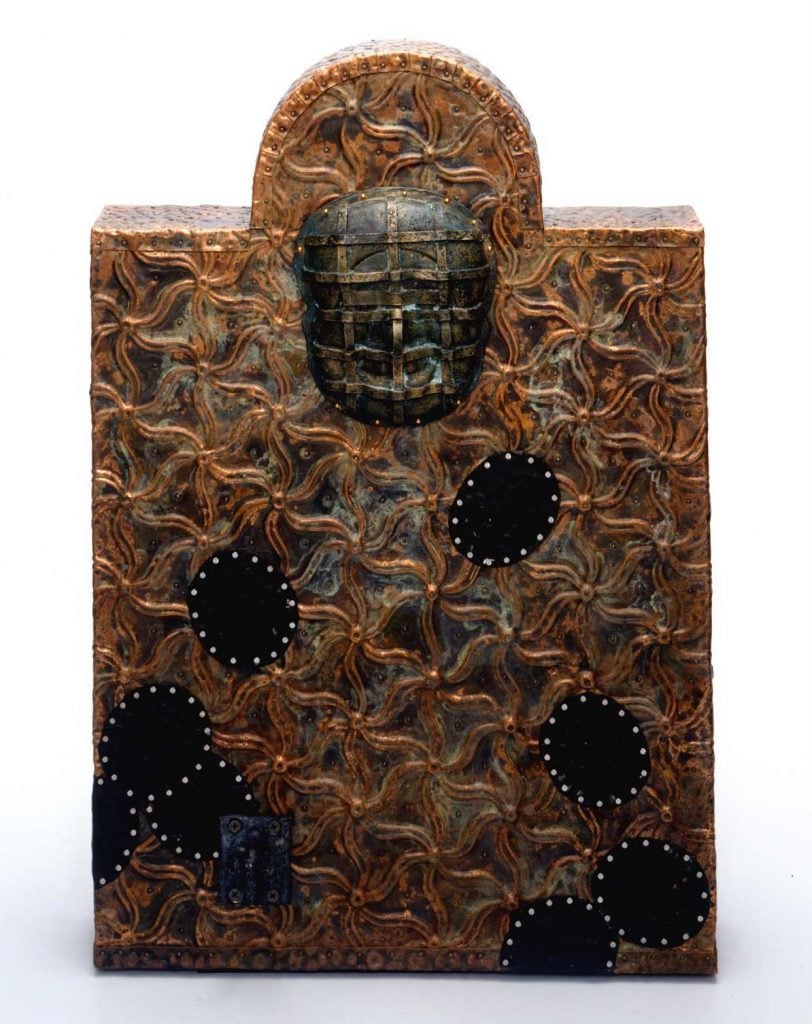

Juan Logan, Some Get/Got Away (2000). Courtesy of Dameon and Kimberly Fisher.

Over the years, the couple has continued to heed the advice Goings gave them during that first meeting: “So you’re taking these things that artists create,” he’d said, “but what are you going to do with them?

“You’re going to share them with as many people as you can,” he continued, “and you are going to do it in the right way.”

A version of this article appeared in the fall 2021 Artnet Intelligence Report, available in full exclusively to Artnet News Pro members. To read more about the art collectors shaping the future, the tech tools poised to revolutionize the art world, and how much money NFTs are actually making for auction houses, download the full report here. If you aren’t yet a member, you can subscribe here.