Coming into the fall auction season, Phillips is again seeking to punch a hole in the prows of its arch-competitors Christie’s and Sotheby’s by assembling top-quality, irresistible sales of contemporary art—which would mean luring both buyers and consigners away from its rivals. Of course, such a red-water strategy is not so easily accomplished. It requires Phillips—which has of late assembled an all-star team of auction rainmakers, like Cheyenne Westphal and Robert Manley—to also create generous inducements in the form of guarantees to land the best works.

Edward Dolman, the Phillips CEO who has been busily transforming the company since his arrival in 2014, is bullish on guarantees. (He has also just hired Philip Anders, the former strategic financial advisor to the Qatar Museums Authority, where Dolman worked too, to help keep his auction house’s coffers under control as chief of staff.)

But guarantees alone can’t overcome all the challenges of the white-hot contemporary market, as was seen a few days ago when Phillips was forced to pull a Mark Grotjahn lot from its September 19 “New Now” sale after the highly in-demand artist posted a note on Instagram saying, “Yo Phillips… I’m not sure I made this. Either way it sucks.” (The house is currently trying to ascertain the lot’s legitimacy.) And even third-party guarantees carry significant risks, as Dolman found out in the case of a deal over a Gerhard Richter painting last November that went badly awry.

To find out how guarantees play into the vision for Phillips—and how Basquiat, China, and watches figure into this vision as well—artnet News’s editor-in-chief Andrew Goldstein sat down with Dolman for the second installment of a two-part interview.

Christie’s and Sotheby’s have tremendous brand cachet. As a result, to lure top consignments and build the Phillips brand, you have been offering plentiful guarantees. In fact, you once said, “The problem is you’re dead if you can’t offer guarantees.” How would you say these guarantees are helping to drive the overall strategy at Phillips?

Guarantees are absolutely part and parcel of the business, and have been for decades now. If handled properly, a guarantee is a very good financial instrument that suits the people that are selling and potentially the people taking on the risk. It’s only when, in the heat of competition, crazy amounts of money are offered on works of art that just aren’t worth it that you’re in trouble.

Frankly, if someone looked at guaranteed objects that have been bought in by the house over the last 25 years—i.e., the guarantees that have gone wrong—you would see an exponential growth in value. So even guarantees that fail to sell can be beneficial for an auctioneer, because they bring in very good art—as Sotheby’s and Christie’s hold in quite significant depth. It was very interesting to know that Sotheby’s had recently been selling a lot of that inventory, and I’d imagine doing pretty well out of it. Unless you’ve made a horrendous mistake, guarantees can actually be a very good store of value for the company.

But an auction house might have to hold onto a work for 10 years or so before selling it, right?

You’re pretty safe on most things after five years, really. Guarantees aren’t inherently evil or damaging to the market, and you wouldn’t be able to compete unless you offered them, because it’s something that all the consignors are interested in hearing about. I think stupid decisions around guarantees can be dangerous, but that’s the same for lots of business decisions.

How do you balance the risks and benefits of guarantees with the need to generate margins in an unpredictable business?

Well, guarantees remain actually the biggest opportunity for an auction house to make significant margins. If you back something and it does well, you get to keep the full buyer’s premium and some of the upside, so your margins are extremely good. If you’re prepared to take the downside, and you’re happy to end up with that object at that price, then that’s not the worst, either.

The challenge of margins really comes from non-guaranteed situations, when you’re just offering brokerage services. Then it does become a very commission-sensitive discussion. I’m afraid to see this slightly inevitable creep of buyer’s premium, driven by deals [that involve] giving up more commissions in order to acquire the best things to put in your sale. If there’s no guarantee in place, then you have to do pretty aggressive deals to get a top consignment, and that has driven up the buyer’s premium significantly.

At the same time, guarantees played a major part in the tremendous turmoil at Christie’s and Sotheby’s over the past several years, where we’ve seen a shareholder uprising at Sotheby’s and dramatic changes in leadership at both houses, along with an exodus of top specialists. In-house guarantees came to be seen as the equivalent of the collateralized debt obligations during the financial collapse, and for a while were shunned in favor of having third parties back them to outsource risk. What happened during this period?

Some of the instability we’ve seen at the main auction houses over the last couple of years is the result of a determination to find a different path to profitability, preserve that profitability, and generate a bigger return for the shareholders. There was a period of explosive growth after 2010, but it didn’t result in huge increases in profitability because of the cutthroat competition around commissions, and because of guarantees being pushed to levels that were unsustainable.

This madly competitive environment was fueled by the cheapest money that anyone’s ever seen. If you give the world’s richest people an endless line of credit at 0.5 percent, they’re going to spend it!

By 2012 or 2013, shareholders realized that this explosive growth hadn’t actually impacted on the bottom line at all—and, in fact, the houses were probably not as profitable as they had been in 2010. Having seen their sales increase by 40 or 50 percent, it was clear that something was going wrong. The pressure put on Sotheby’s to reinvent itself was part of that, and the changeovers in Christie’s CEOs—with three in recent times—has been about trying to find some alternative model to improve their basic profitability.

That’s why I think Phillips is very well situated. We have a much smaller cost base than Sotheby’s and Christie’s, and we need far fewer sales and much less revenue to make a profit. We’re also focusing on an area of the market that has a quite significant amount of supply, a huge amount of demand, and pretty high values. At Phillips, the average lot value is significantly higher than Christie’s or Sotheby’s—if you average up all the lots we sell and divide it by the amounts we’ve sold them for, it comes to about $110,000, which is a very nice place to be. And the commissions are pretty strong in that area.

But you’re not comparing contemporary art at Phillips to contemporary art at Christie’s or Sotheby’s.

It’s the average of art across the board. But that’s what the business is about. You’ve got infrastructure to pay for, you’ve got catalogs, warehouses, websites—all those costs are shared out pretty evenly among the different categories that Christie’s and Sotheby’s sell. And that, I think, puts pressure on their cost base, and pressure on their margins.

It’s very interesting, here, to note that one of your first moves when you came in at Phillips was not to bring on a high-powered art specialist but rather a watch connoisseur, Aurel Bacs, who had previously been at Christie’s and is reputed to be the best in the business. You now have the world record for a wristwatch—a rare stainless-steel Patek Philippe that sold for $11.1 million last November—and it’s possible you might best that record next month with Paul Newman’s Rolex Daytona, which the New York Times called “basically the Mona Lisa” of watches. How big a profit center are watches for Phillips?

The watch business has been fantastic for us. There are very few individuals working in markets who have the power that Aurel Bacs has. It was opportunistic, because at that particular time, Aurel was being pressured to do mass online watch-auctioneering, which he knew was fundamentally flawed, and he didn’t want anything to do with.

We were the lucky recipients of that clash of ideology—because, of course, I agreed with Aurel absolutely. I am a huge supporter of what the internet can do for the art business—[but] I remain skeptical about its ability to enable sight-unseen transactions at very high levels between relatively small numbers of people. We’ve seen Paddle8 try and effectively fail, Auctionata fail, eBay fail to get their average lot value up from about $700 or whatever it is.

At the moment, the primary way that the web has transformed our business is by allowing direct online bidding during our sale. Now we can broadcast our sales all over the world, we can send our catalogs by email, we can do digital advertising campaigns, we can send out videos of artists talking about their works through our website, and we can reach so many new people and invite them to partake in our sales. But there is still quite a bit of work to be done in terms of getting effectively sight-unseen transactions to happen at a very high level.

Phillips struck a partnership with eBay in 2015 to do some lower-priced auctions through the site, but when I went to check out the Phillips page on eBay recently, I saw that there hasn’t been an update since April, and there’s nothing on the advance calendar. Is that experiment over?

We always saw eBay essentially as a marketing tool—as a way to potentially take ourselves to more people at very little cost. I think it worked to a certain extent, but we’re now seeing more players coming into that market who seem to be more effective. Artsy, for instance, brings together like-minded people who have an interest in the art market. I don’t think eBay has got that same focus.

To go back to the watches for a moment, it must make you sleep well at night, with the contemporary sales coming up, to know that on October 26 you’ll have the Paul Newman watch sale. A sale like that is catnip for the world’s enormous pool of wealthy watch obsessives, who are willing to pay incredible amounts of money for something that you don’t need to jump through quite as many educational hoops to desire. It is also a great profit center to counterbalance any risks taken in the art auctions, I would guess.

It’s true, the watch market has been an extraordinary success story, and an extraordinary growth story. Who would have ever thought that a stainless-steel Patek Philippe would sell for over $11 million at auction? If you’d have said that three or four years ago, people would think you were crazy. But it’s the perfect example of a category that has benefited hugely from global wealth and global recognition. That said, it’s still mostly vintage watches—modern watches remain less desirable.

Are there any other high-profit areas that are outside of contemporary art and design that you can see Phillips going into?

We’re obviously determined to build up our jewelry department, but until the right people come along, there’s no point in attempting to start something. We have a great team in Hong Kong that is selling jewelry for us now, but we need to flesh out that department because we’re determined to bring it to London and New York. That’s next on my to-do list.

Christie’s and Sotheby’s have enormous portfolios of different businesses, from Old Masters to historical American furniture. Some of these older businesses are dying. It sounds like Phillips now has the opportunity to start from more of a blank slate, and build something new.

That’s the great thing about Phillips—the element of the blank canvas, where you can choose the areas that you want to develop rather than having to deal with the problems associated with changing taste and the dwindling of demand. But, you know, people think the Old Master picture market is a dwindling collecting category—and I don’t think it is. It’s just that it’s about the same size as it was 20 years ago, and postwar and contemporary art dwarfs what’s happening in Old Masters.

Debuting fresh young art stars has been a longstanding part of the Phillips DNA, and during the flipper era, the auction house fueled a number of boom markets, earning staggering prices early on for people like Lucien Smith, whose senior thesis painting sold for $389,000 in 2014, and Oscar Murillo, whose short-lived record of $401,000 was notched at Phillips in 2013. Most recently, you lent some market heat to the 2017 Whitney Biennial painter Celeste Dupuy-Spencer, whose painting Ceviche and Peruvian Meat sold for more than twice its low estimate this spring. Is being a tastemaker and launching the equivalent of IPOs for the markets of rising artists still a priority at Phillips?

It’s important for us to continue to bring high-quality new art to our clients, and we do have a role in terms of picking the right works and trying to predict the stars of the future. But it’s a different market today—the stories of flipping young artists, and dramatic increases in their prices followed by collapse in value, is not something the galleries want to see, and it’s not something the auction houses want to see. We want steady, solid markets created for everyone.

So I think those furious times of 2012, 2013, 2014, when you saw fairly irrational amounts of money being paid for young art, just as a punt, really—artists suddenly going up to $950,000 and then, six months later, back down to $50,000—are over. The world’s learned from that. The market is much more savvy.

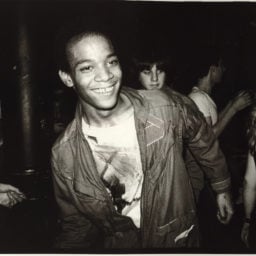

These days, the artist whose work you need to have in a sale to be a credible player is Basquiat. His market has been a rocket, and the recent $110.5 million sale that made him the priciest American artist of all time only added more fuel. Phillips has underwritten an exhibition at the Barbican called “Basquiat: Boom for Real,” which is a humorous title because it sounds like a prayer from the lips of the art market. What do you think is going on in the Basquiat market, and is this “boom for real”?

Exceptional Basquiat works make a large amount of money now—and that’s not a boom. Basquiat is one of the most recognizable and important artists of his time. He also resonates so strongly with the next generation that is coming up—it’s something about the way he portrayed energy, philosophy—and that’s why you see younger collectors like Yusaku Maezawa in Japan feeling such a strong connection with his art.

So this is real and it’s going to stay, just like Andy Warhol is real and is going to stay. There are big differences, though, because lesser Basquiats are not worth $20 million or $30 million. It will be interesting to see how the market adjusts over the coming seasons. But we’re delighted to be associated with that Basquiat exhibition, and I think he’s going to be a major player for all the auction houses in the future.

Do you have any big Basquiat consignments coming up for your fall season?

I believe we do, but I can’t confirm anything just yet.

Speaking of consignments, you had a major consignment from Paul Allen a little while ago that has opened up an enormous can of worms, in a way that says a lot about the present moment. Gerhard Richter’s Düsenjager (1963) was expected to sell for more than $25 million at Phillips’s big November evening auction, and it carried a $24 million guarantee from the 29-year-old Chinese businessman Zhang Chang. The photorealistic jet painting failed to sell at auction, and now Zhang is refusing to pay, saying he doesn’t have the money. Meanwhile, Phillips has put a hold on a $15 million Francis Bacon owned by Zhang to recover some of the money, but that painting is the subject of a lawsuit in China, from a man who says it is rightfully his—meaning there is a chance, if the court rules in that plaintiff’s favor, that Phillips will be left holding the bag. It’s obviously a terrible mess. Where do things stand now?

I wish it was more unusual than it is, but every now and then people do have trouble paying their debts. We’re hoping that we’ll get a resolution to this matter fairly quickly, and I’m pretty confident that we’ll be paid. But the important thing for people to understand is that Phillips 100 percent honored its commitment to the seller—the seller has been fully paid out. So even though we are still chasing the buyer, the guarantee is absolutely solid. Unfortunately, because the buyer is Chinese, the jurisdictional issues have been a little bit more complicated, which is why we had to put a hold on property that we think is his—to hold his feet to the fire to get him to pay. At this point, that’s it.

This is a particularly notable case because there is so much opportunity in the Chinese market—so many big American players seem to be expanding into Hong Kong and Shanghai—but at the same time, the risk of non-payment is remarkably high in China. A recent survey of the Chinese art market found that only 51 percent of buyers actually followed through on paying for the work they purchased last year. If you take out the non-paid auction sales, the Chinese art market actually shrinks remarkably. So, how can Phillips minimize risk when dealing with this increasingly important clientele?

We tend to only want to sell to people who we know can pay. Credit checks have been part and parcel of our business for years. In China, you have to be super careful, and various measures have been taken over the years in terms of making sure that people have a certain amount of money deposited in an account before they bid, so you know they’re good for it. Then, if they default, you’ve got the deposit money. It’s not that different from the way that auction houses have traditionally managed their risk of payment default.

What about third-party guarantees? Is there a different calculus?

No, the guarantees are exactly the same. Also, the default on the Richter jet was not by an unknown person who hadn’t already been in the market at a high level before. We did our due diligence. So we were surprised when he wasn’t able to meet his payment obligations to us.

You recently had your first fully fledged evening sale in Hong Kong. How much potential do you see in China? And do you see yourself actually establishing a base of operations there?

Oh, definitely. We do have quite a large office now in Hong Kong.

What about an actual salesroom?

We don’t have a salesroom—but none of the major auction houses have a salesroom in Hong Kong anymore. It’s ferociously expensive real estate, and to hold a large selling area for two main seasons a year doesn’t seem to be a viable business decision. I don’t think you’ll see many auction houses with full-scale salesrooms in Hong Kong. We have smaller areas that we use for exhibitions and where we can do very small auctions, and we do have a full-time office.

I think the potential for China is self-evident—it’s potentially the largest growth market for the art business, anywhere. I think that’s why you’ve seen Asian interest in the shareholdings in Sotheby’s and why you’ve seen Asian corporations looking at what opportunities there might be left. Chinese bidding into the sales in London and New York is really significant—in every sale, we are now happily selling to Chinese people who pay.

In the broader auction market, there have been giant fluctuations lately. Phillips obviously did very well last fall, but overall the market fell by 50 percent between 2015 and 2016. Now, going into the fall of 2017, we are in a very strange political moment, and the stock market is flying extraordinarily high. What would you say is the climate in the art market? What is the confidence level among consignors and bidders coming into the fall season?

I think it’s pretty good. We’ve seen a fairly steady recovery over the last year or so in the sale totals. But I will say that it feels a bit different from other upward ticks, because there is so much geopolitical uncertainty at the moment, from Brexit to North Korea. No one is going to bed at night thinking everything is fantastically fine. But if you look at the measurable economics—stock markets, economic growth, wealth—everything seems fine. We’re looking forward to November, but I don’t think we’ll see 2017 being 50 or 40 percent up globally from 2016. We’ve seen some recoveries that have been as sharp as that, but I don’t think we’re going to see that this year.

Just last week, following similar recent actions by Sotheby’s and Christie’s, Phillips raised its buyer’s premiums again, after increasing those same fees just over a year ago. How did you calibrate the recent increases and why did you feel it was necessary? Does Phillips have to do it simply because Sotheby’s and Christie’s did?

We make our own decisions about what is an appropriate fee structure for Phillips. We felt it was necessary to help fund our continuing expansion in Asia as well as needed investments in New York, London, Geneva, and other parts of the world. In the past few years, we’ve made senior global hires, opened a new headquarters in London, established a 20th-century art department, launched a watch department, and expanded our digital offerings. In addition, building a strong presence in Asia has been a leading priority for Phillips ever since I started as CEO three years ago. We remain very much in expansion mode.

Click here to read the first installment of this interview.