Art World

Debunking Basquiat’s Myths: Curator Eleanor Nairne on What We Get Wrong About the Misunderstood Artist

Ahead of the Barbican exhibition, we spoke to the show's curator about why it's time to look at the artist’s oeuvre with fresh eyes.

Ahead of the Barbican exhibition, we spoke to the show's curator about why it's time to look at the artist’s oeuvre with fresh eyes.

Lorena Muñoz-Alonso

The support for Jean-Michel Basquiat’s work in UK’s museums had an auspicious start: In 1984, at the Edinburgh-based Fruitmarket Gallery, the curator Mark Francis staged the first exhibition of the American artist in a public institution, ever. However, more than a decade passed before Basquiat was the subject of a smaller, posthumous show at London’s Serpentine Gallery in 1996. And since then, over 20 years have gone by without a single instituational show in the UK.

More worryingly perhaps, to this day the UK still doesn’t have a single Basquiat in its public collections, which is why “Boom for Real,” the landmark exhibition of arguably one of the most important painters of the 20th century at London’s Barbican Art Center, is so hotly anticipated, and much needed. Opening to the public this Thursday, the exhibition has been curated by the Barbican’s Eleanor Nairne and leading Basquiat expert Dieter Buchhart—who has organized a number of key exhibitions on the artist, including a retrospective at the Beyeler Foundation in 2010, and the artist’s survey “Now’s the Time” at the Guggenheim Bilbao in 2015.

Those expecting a straightforward painting show are in for a surprise, however. Because the Barbican is a multidisciplinary arts center, made up of galleries, theaters, concert halls, and cinemas, “Boom for Real” will give viewers the chance to look at Basquiat’s oeuvre from a cross-arts vantage point, including not just the artist’s visual art production, but examples of all the cultural forms cross-pollinating in New York City at the time, particularly in the Downtown scene. In that vein, a whole season of events has been programmed across the center, tracing a portrait of New York from 1978 to 1988, through cinema, music concerts, theater pieces, and other events.

Ahead of the exhibition opening, artnet News sat down with Eleanor Nairne to talk about why this show is so necessary, Basquiat’s obsession with Leonardo da Vinci, and why his skyrocketing market is hindering the serious understanding of his work.

The exhibition’s co-curator Eleanor Nairne. Photo ©Max Colson, courtesy Barbican Art Center.

Let’s start with the exhibition title, “Boom for Real.” What does it mean?

“Boom for real” was one of Basquiat’s favorite phrases, which he would use to refer to anything he’d get excited about. I liked it because no one had titled a Basquiat exhibition using his own words before, and I felt it was quite a powerful thing to do in terms of situating yourself within his viewpoint.

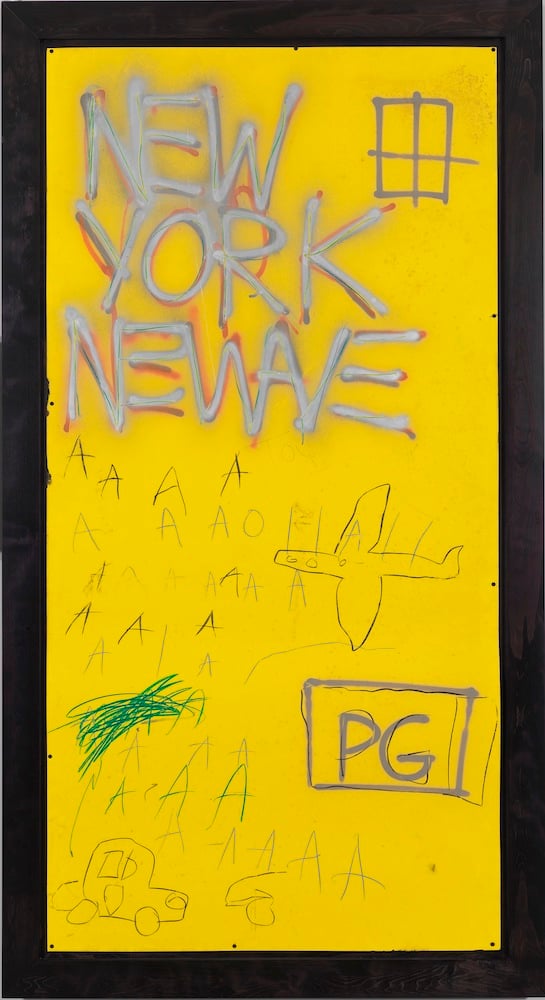

The exhibition is divided into two floors. The upstairs gallery is all about the collaborative energy of the cross-arts New York scene, and showcases his famed postcards; the film Downtown 81, which he stars in; documentation of “New York/New Wave” [an era-defining group show staged at PS1 Contemporary Art Center [now MoMA PS1] in 1981 in which he participated]; the hip hop record he produced; and his encounter with Andy Warhol.

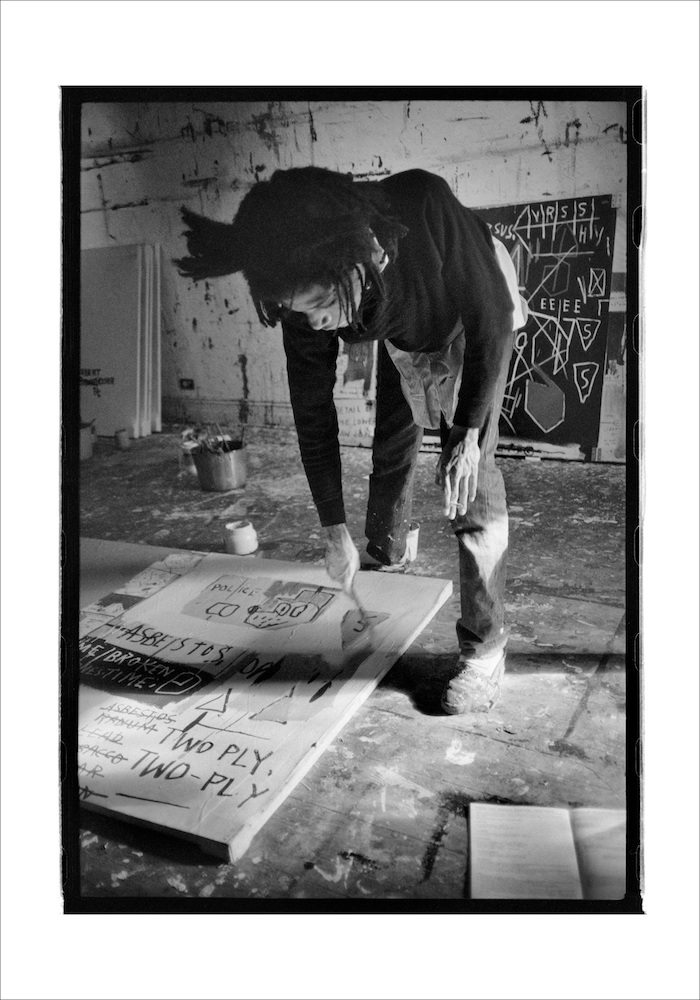

Meanwhile, downstairs is like an explosion of the studio space, including everything he was drawing inspiration from: his record collection, his art history books, and his film collection.

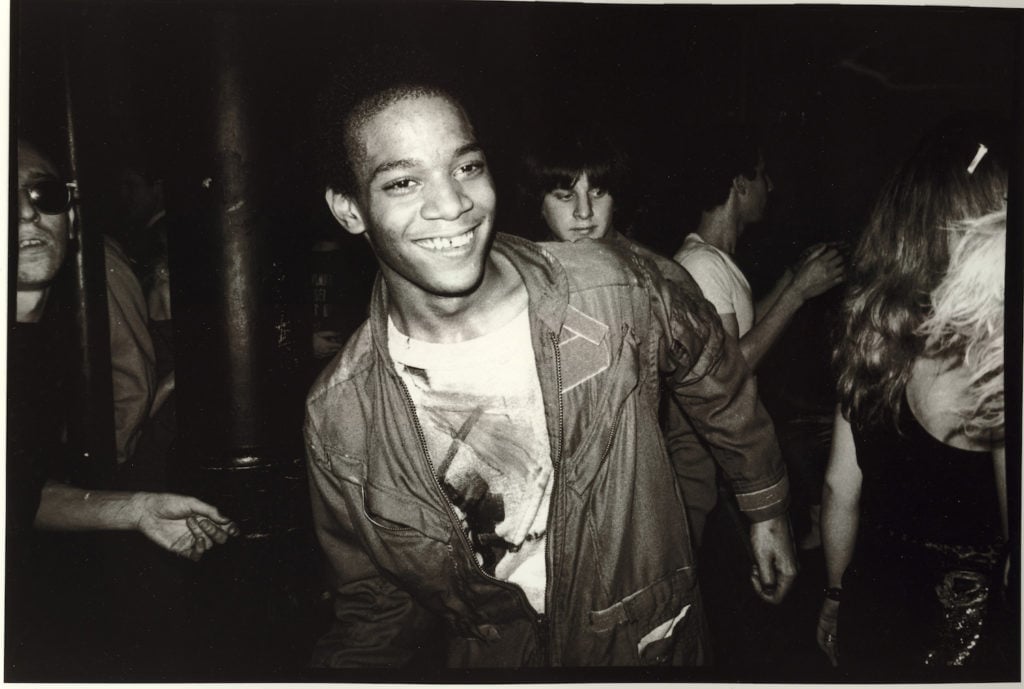

LIKE AN IGNORANT EASTER SUIT, Jean-Michel Basquiat on the set of Downtown 81. ©New York Beat Film LLC. By permission of The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Photo: Edo Bertoglio.

In terms of the actual works, how many Basquiat pieces are you showing?

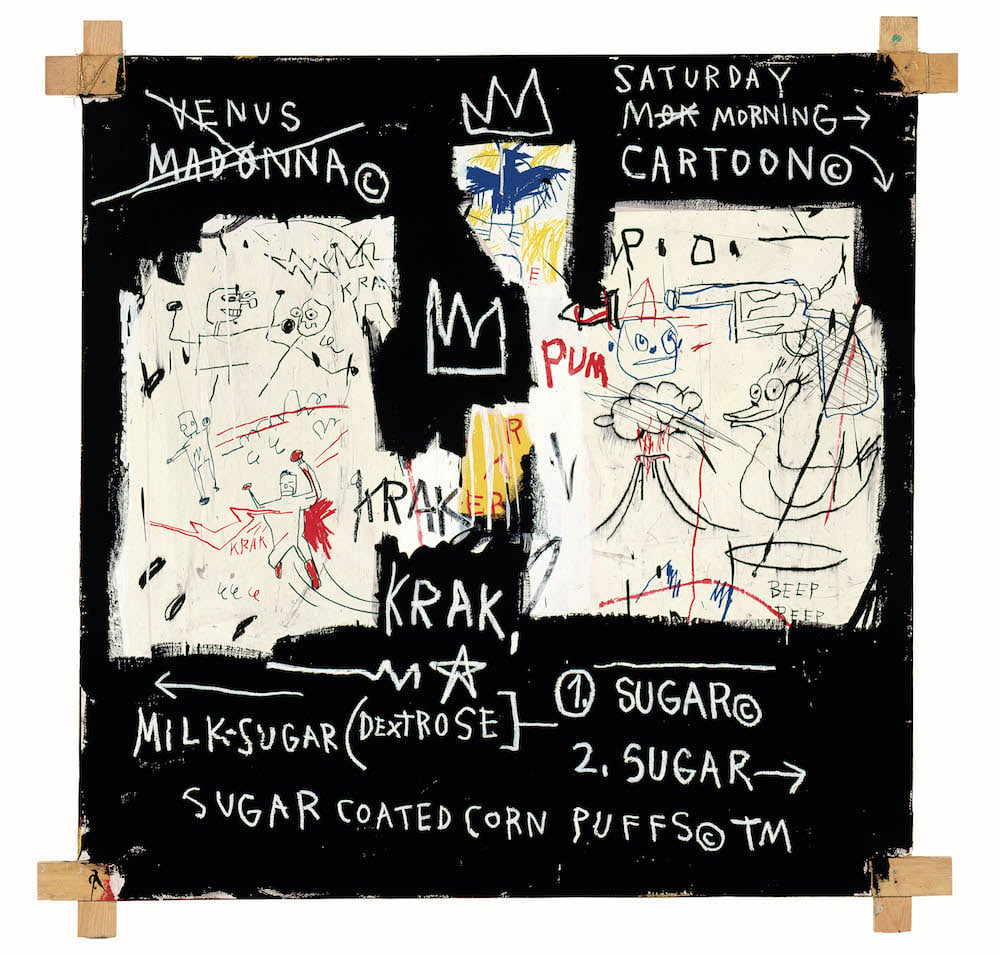

There’s more than 100 works: about 40 paintings and 40 drawings, and then a whole collection of collages, Xeroxes, objects, and a fridge that he and other graffiti artists graffed up. There’s a lot of work, but I think it’s also very important that the show is not just about the painting. There are obviously a number of highlights, but there’s also so much more.

What are the highlights for you?

It’s hard to choose, but some of the Fun Gallery works [exhibited as part of a 1983 show] are definitely a highlight, and to be able to show Leonardo da Vinci Greatest Hits (1982) for the first time alongside his original copy of the Leonardo da Vinci book that he worked from is a total dream.

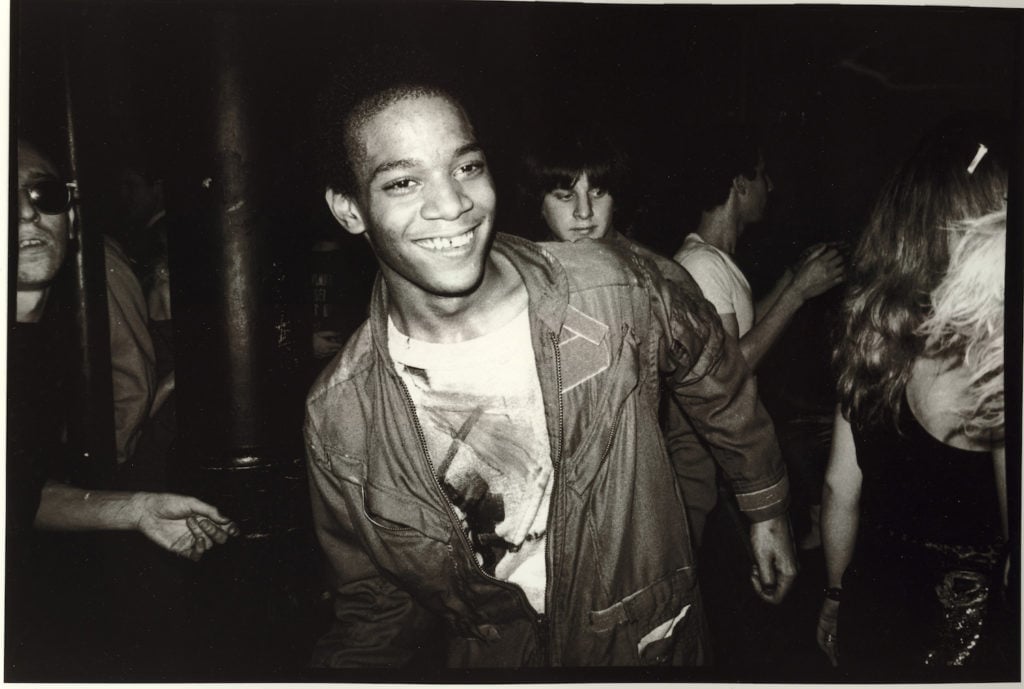

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled (1980). Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. ©The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ ADAGP, Paris. Licensed by Artestar, New York.

That’s so interesting. Why was Leonardo so influential to Basquiat?

Leonardo da Vinci was one of the many figures that he was obsessed with. I think Basquiat was interested in da Vinci because he was the quintessential Renaissance man, and so was Basquiat in certain ways. The New York artist was incredibly plural in his interests and in his pursuits. I think he loved the way in which Leonardo’s manuscripts had lots of diagrams and were heavily annotated and illustrated. That combination of image, symbols, and text was very important to him.

You co-curated the exhibition with the Basquiat expert Dieter Buchhart. What have you each brought to the table?

It’s been a very long process. We’ve been working on this show for almost three years now, and Dieter has brought a huge depth of knowledge about Basquiat and other artists from the Downtown scene, such as Keith Haring. What I’ve brought, perhaps, is an interest in specific areas of Basquiat’s work; for example, thinking about Basquiat in relation to performance and literature.

I think that together we’ve been able to bring something distinct and unique to the Barbican and to the UK, but it’s also a significant step forward in terms of what’s possible to do with Basquiat exhibitions today.

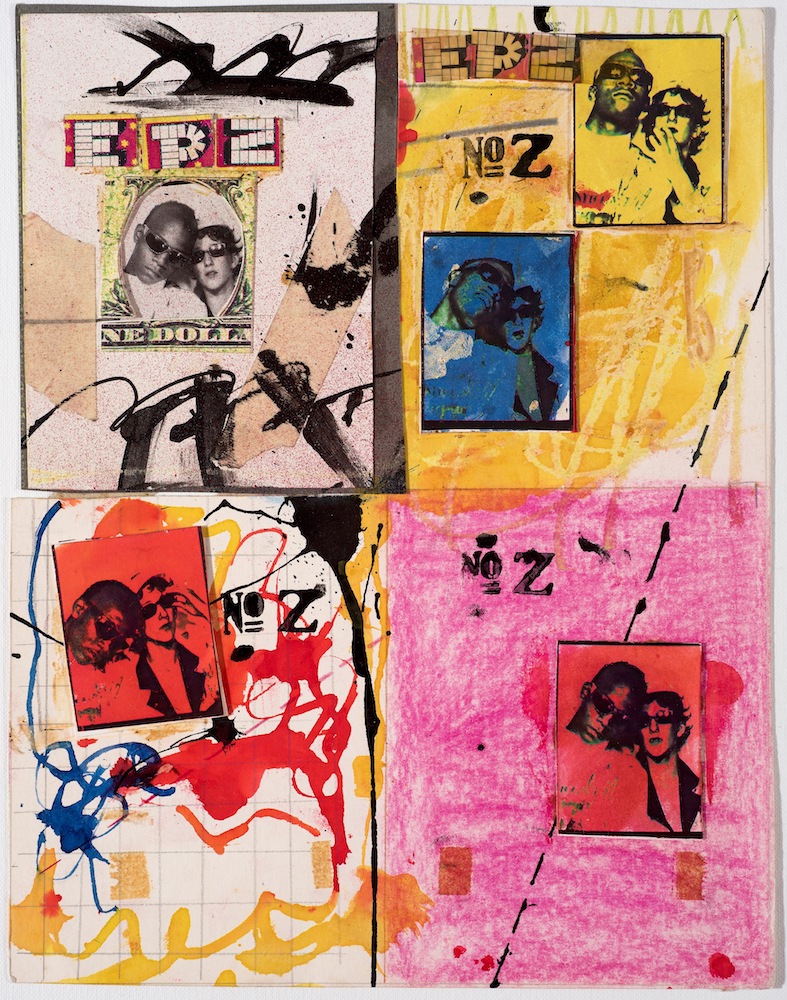

Jean-Michel Basquiat and Jennifer Stein, Anti-Baseball Card Product (1979). Courtesy Jennifer Von Holstein. ©Jennifer Von Holstein and The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York.

Tell me a bit more about this idea of performance in Basquiat’s work.

So this notion is present already in the first work that Basquiat becomes known for: the SAMO tag, which stands for “same old shit.” The tag was created in 1978 with Basquiat’s friend Al Diaz.

During this period Basquiat was attending the City-As-School, which at the time was this new pioneering, alternative high school in Manhattan. The school was inspired by the ideas of John Dewey—learning by doing, and making students use all the activity going on in the city as their syllabus, which makes so much sense in the New York of that time.

So in school, Basquiat teamed up with an organization called The Family Life Theater and it was there, in that theatrical context, that he first started workshopping the idea of a character called SAMO. Furthermore, the idea of intervening with the city, and taking to the streets to write his statements, has a performative aspect.

And this idea of performance continues in his earlier works with collage and postcards—of which we have a whole body of work in the exhibition that has never been shown before—when he was selling them for a dollar in the streets of New York with then-girlfriend Jennifer Stein. The two would create outfits and wear them while they sold their work outside MoMA, in SoHo, and the Lower East Side. This is exactly how he managed to introduce himself to Warhol.

Rammellzee vs. K-Rob, produced and with cover artwork by Jean-Michel Basquiat ‘Beat Bop’ vinyl record, 1983. Courtesy Jennifer Von Holstein. ©The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York. Photo: Justin Piperger.

You told me a few months ago that you felt this show would debunk a lot of myths associated with Basquiat and his oeuvre. What exactly did you mean by that?

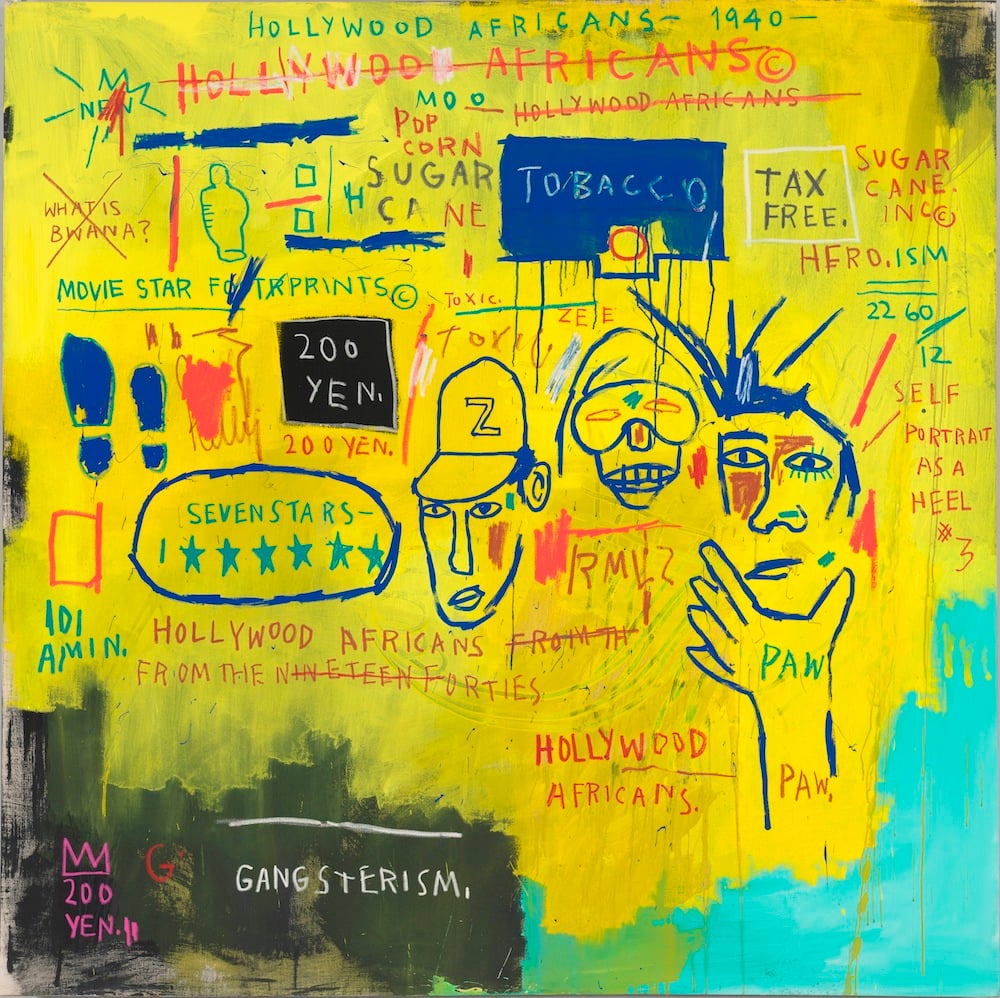

I think our goal was to be able to situate him as a serious artist and as somebody who was incredibly canny in terms of what he was producing. Sometimes the discussions around him have robbed him of agency, making him sound as if he was either creating the work almost against his will, as if he wasn’t fully conscious of everything that he was doing within these quite complicated visual compositions. I think that what we are doing with this exhibition is to show people that there was an incredible mind at work behind all this.

He was also true to the spirit of the day, which was of course the period of postmodernism, and about the clash between low and high culture, and the proliferation of multiple meanings. His work was really a space in which he could play out all of the different areas from which he drew inspiration, and I think that hasn’t really been understood with a degree of sensitivity before. So hopefully we are allowing a very different, fuller picture of him to come through.

What misconceptions do you think are attributed to him?

Some people might not know that Basquiat came from a very cultured background. His father was an accountant from Haiti and his mother was second-generation Puerto Rican. He was the eldest of three siblings and grew up in a brownstone in Brooklyn. In the 2015 notebook exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum they were able to show his original junior membership card to the museum, so that tells you that he was exposed to an incredible amount of art and exhibitions from a young age.

He also attended the private school St. Anne’s, and then later the progressive City-As-School. So he had a very educated background, even though he dropped out of school at a relatively young age. I think people tend to think that he didn’t have much of an education, but actually he did.

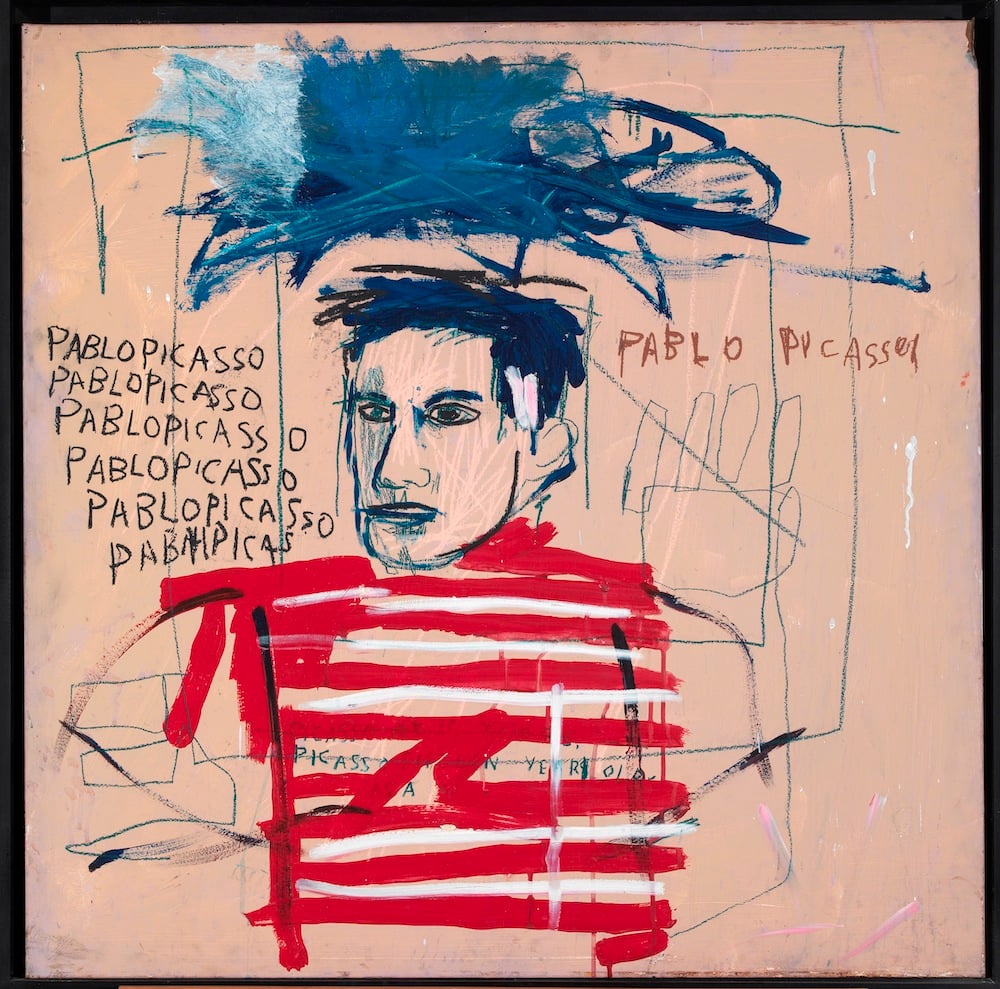

He said in an interview: “I’m just an autodidact who would like to be part of the family of artists.” Sometimes when someone hasn’t received traditional artistic training they almost exert themselves even more to be able to prove their knowledge. He really consumed the Western canon of art history as well as being fascinated by art from Africa, and folk traditions.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled (Pablo Picasso), 1984; Private collection, Italy. ©The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York.

In the last few years, most of the conversations around Basquiat have had to do with his skyrocketing market, and the fact that his work is bought by super-collectors and celebrities. What do you think this has done to the understanding of his work?

Well, people are mostly familiar with a very small sliver of his work, which was made between 1981 and 1982, and associated with ideas of neo-expressionism. These are the pieces that fetch these incredible prices at auction.

But in reality he constantly reinvented his practice at a fast pace, going from graffiti to collages and xeroxes, to painting these baseball helmets to be used in performance pieces, to designing clothes and selling them at Patricia Field’s shop, and then participating in a film. He was actually thinking about making films himself towards the end of his life.

So the focus has tended to be on particular works that have been sold and have attracted a lot of media attention, but that has really detracted from a fuller understanding of his work.

Basquiat might be a market darling but his work is not very present in museum collections, and I quote from AFP, “Out of the more than 2,000 works of art that Basquiat produced, New York’s MoMA has just 10 drawings and silkscreens, the Whitney has six, the Metropolitan two, the Brooklyn Museum another two and the Guggenheim one.” In what specific ways is that a problem?

Generally, what produces understanding of an artist’s work is scholarship, and that comes off the backs of institutions or independent academics that are focusing on that artist’s work. And both those things have been made quite difficult in Basquiat’s case by the fact that there are almost no works by him in public collections. There’s not a single one in the UK, but there are also very few internationally—although there are some, and very important ones, in museum collections. This puts a lot more emphasis on what exhibitions are able to achieve in terms of generating scholarship.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Hollywood Africans (1983), courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. ©The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ ADAGP, Paris. Licensed by Artestar, New York.

Obviously now his works are incredibly expensive and out of reach of most museums’ budgets. But why did museums not collect earlier, do you think?

I think many institutions were very aware of the importance of his work in his lifetime. In fact, his first show in a public institution took place here in the UK, at the Fruitmarket Gallery in Edinburgh in 1984, which then toured to London’s ICA and the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam. But he died incredibly young, and by the time his works did become available they were already incredibly expensive. Now, international museums are in a position where they are reliant on collectors’ generosity to bequeath works to them.

Do you think he would like the status and the prices his work fetches today?

He was very determined about the artist that he would become. It’s very clear from interviews with his family and friends that he never doubted the celebrity he would attain and that he would be one of the most significant figures of 20th-century painting. He knew that before he even had any money to buy materials to make paintings and, in that sense, I think he would be pleased.

Jean-Michel Basquiat painting, 1983. ©Roland Hagenberg.

A lot of younger artists are mentioning Basquiat as an influence at the moment, even artists like Anne Imhof. Why do you think his work resonates so much with the younger generation?

I think it perhaps has to do with the complex way in which he handles his own identity, which I think is incredibly prescient, and not just in his use of monikers and pseudonyms like SAMO or Aaron. I think that in some ways he’s a precursor to that generation of artists shown in the famous “identity politics” iteration of the Whitney Biennial in 1993, who were interrogating the way in which their identity inflects their work and how they are considered.

There’s a line in Rene Ricard’s The Radiant Child essay about Basquiat in which he says: “One must become the iconic representation of oneself if one is to outlast the vague definite indifference of the world.” To me, this is about how, in order to survive in New York, you have to have this clarity about your own image, of what New York demands of you as an artist. It’s about Basquiat reading how others are reading him, how he feels being othered by others.

What do you want viewers to take away from this show?

The thing that makes me feel incredibly grateful to have been able to spend this amount of time in the presence of this artist is that I feel like I’m in the company of a man who is ferociously intelligent and incredibly funny. And I think you don’t get to experience that when you are looking at reproductions. It is something you can only really experience in the flesh, and a whole generation has come of age here without that opportunity. So I hope that everybody who comes to see the show will get the chance to enjoy that spirit.

“Basquiat: Boom For Real” will be on view at the Barbican Art Gallery, London, September 21, 2017–January 28, 2018.