Galleries

Europe’s 12 Best Exhibitions in 2014

artnet News’ European editors hand out the accolades.

Photo: Courtesy Thomas Dane Gallery, London

artnet News’ European editors hand out the accolades.

Alexander Forbes &

Coline Milliard

artnet News’ European editors Alexander Forbes and Coline Milliard pick their favorite shows of 2014, presented in chronological order.

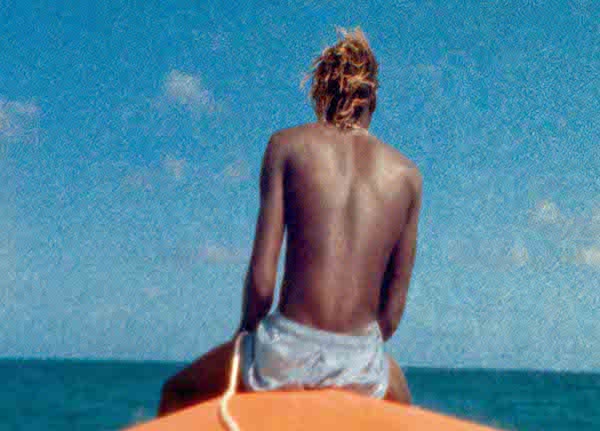

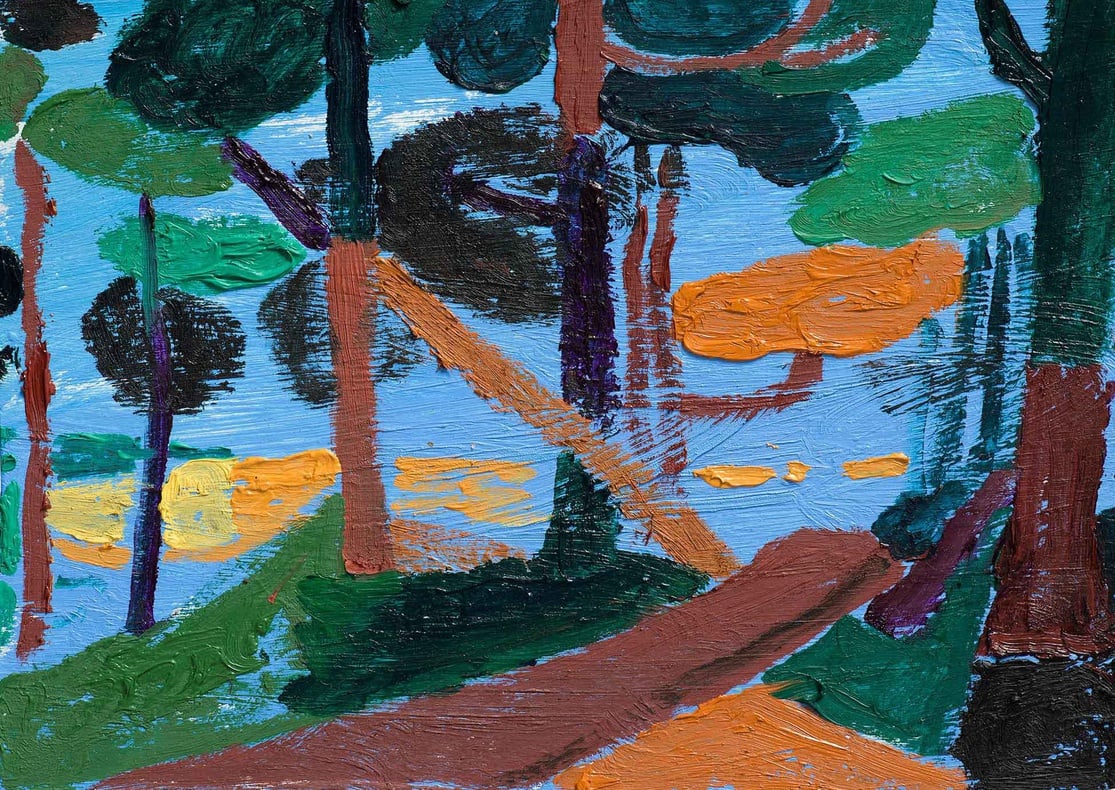

Tal R, Walk towards Hare Hill (2013) (detail)

Photo: Courtesy Victoria Miro Gallery

Tal R, “Walk Towards Hare Hill” at Victoria Miro, London Mayfair

There was something intensely refreshing in Tal R’s series of paintings Walk towards Hare Hill, presented at Victoria Miro earlier this year. It showcased work produced in the summer of 2013, while the artist was holidaying in Northern Denmark. The series is a powerful demonstration of the creative role of constraint. Concentrating on small formats and the very same few spots, where he painted en plein air daily, Tal R managed to say something new about the place in each piece. The color changed, and the motifs shifted, but every work took us that one bit closer to the essence of the landscape in this part of the world (see In Review: London’s Top 10 Exhibitions, from Herald Street to David Zwirner). —CM

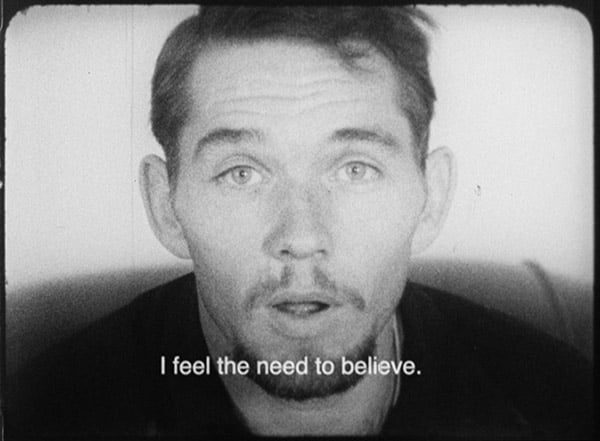

Jeremy Shaw, Quickeners (2014)

Photo: Courtesy Johann Koenig, Berlin

Jeremy Shaw, “Quickeners” at Johann König, Berlin

The titular 36-minute-long video work from Shaw’s show this past spring is set 400 years after human extinction when a new species, dubbed Quantum Humans, inhabits the planet, immortal and interconnected through an exhaustive catalogue of all things knowable called the Hive. Presented in a documentary mode and pulling from archival footage of a ritualistic cult of revivalists from the 1960s, the piece chronicles sufferers of what’s called Human Atavist Syndrome (H.A.S.) who have reverted to activities of abstract value creation and illogical root: music, dance, and religion, among them. It’s an odd set-up. And later in the year, I came around to questioning if my initial enthusiasm for the piece had been misplaced (see Berlin Gallery Beat: Must-See Shows in June). But watching it through again confirmed both that enthusiasm and Quickeners‘s place as the most important single piece I saw this year. —AF

Otobong Nkanga, Diaspore (2014)

Photo: Courtesy MCH Messe Schweiz (Basel) AG

“14 Rooms” at Art Basel in Basel

I had been dying to see this show since its first iteration, “11 Rooms” at the Manchester International Festival in 2011. Yet, I worried that the experience would be cheapened somehow by the commercial context of Art Basel. I was wrong. “14 Rooms” was by far the most enjoyable hour I have ever spent at a fair. And, even held up to institutional exhibitions throughout the year, it shines. That’s thanks to its unique, one-performance-work per-room-design, which forces viewers to slow down and actually contemplate the art presented before them. Even in museum galleries today, that scarcity of looking pervades. —AF

Daniel Buren, “Défini Fini Infini, Travaux in situ,” Mamo, Marseille

Photo: Coline Milliard

Daniel Buren, “Défini Fini Infini, Travaux in situ” at MAMO, Marseille

It was a match made in heaven, or at least in the deep blue skies of the Mediterranean. Daniel Buren took full advantage of the possibilities afforded by the rooftop and gymnasium of Le Corbusier’s Cité Radieuse in Marseille. Outside, his gigantic navy blue sculpture gave a point of focus to the unraveling panorama, and conversed with the immensity above. Inside, the colored glass and mirrored space turned a small modernist structure into a dazzling cathedral. —CM

Emma Rushton and Derek Tyman, Flaghall (2005)

Photo: Courtesy the Edinburgh Art Festival

Edinburgh Art Festival

Curating the Edinburgh Art Festival was a tall order this year: not only was Scotland about to cast its vote on independence, but Glasgow was hosting the Commonwealth Games. EAF addressed both with brio (see Edinburgh Art Festival Gets Political). It took over the oddly futuristic Old Royal High School, repurposed as the New Parliament in the 1970s and meant to host a devolved Scottish Assembly that never came to be. Inside glowed Amar Kanwar’s eerie film installation on land appropriation in India, subtly asking what right people have to decide the destiny of the land they occupy. The Commonwealth took center stage at the City Art Gallery, in a sprawling exhibition put together by five curators hailing from different corners of this cumbersome post-colonial entity. The result, which gathered works by the likes of Uriel Orlow, Shilpa Gupta, and Rebecca Belmore, was as ambitious, messy, and compromised as the Commonwealth itself. It was the only way it could be. —CM

Kate Cooper, “Rigged” at KW Institute of Contemporary Art, Berlin

Photo: Courtesy KW Institute of Contemporary Art, Kate Cooper

Kate Cooper, “Rigged” at KW Institute of Contemporary Art, Berlin

KW returned to form as an instigator of cutting-edge contemporary art with this show of yet-gallery-less Kate Cooper. Best known for her collaborative London exhibition space, Auto Italia South East, the Liverpool native was awarded the Ernst Schering Foundation Prize this year and presented an uncanny installation of CGI images and animations at KW. Though in their very essence infinitely customizable beings, Cooper’s models are presented in various processes of image-perfection—orthodonture, fitness, makeup—keenly suggesting that, rather than the end result, it’s the consumption based process of self-betterment (and the constant socially-constructed flux of what “better” actually means) to which we’re addicted. —AF

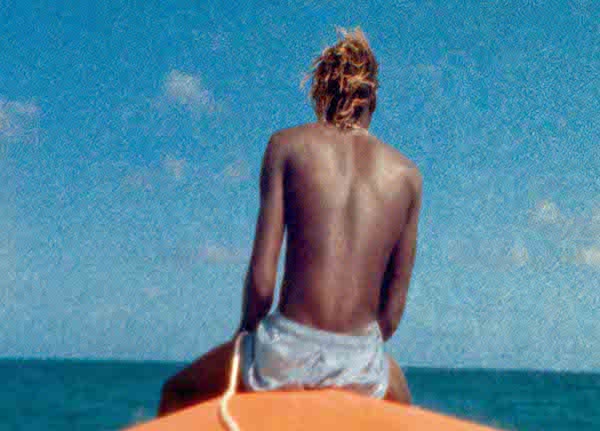

Steve McQueen, Ashes (2014)

Photo: Courtesy Thomas Dane Gallery, Marian Goodman Gallery, © Steve McQueen

Steve McQueen, “Ashes” at Thomas Dane Gallery, London

Steve McQueen’s Ashes took me by surprise. After 12 Years a Slave, Shame, and Hunger, I had come to associate him with the lush aesthetic of mainstream cinema, and Ashes is anything but that. These grainy images of a youthful man on a boat are so fresh and immediate they seem to have been shot on the spur of the moment, almost by accident. And the contrast between the man’s warm smiles and the gritty story he narrates—drugs, death—is a punch in the stomach. McQueen might have found in Hollywood a medium to match his ambition (see Oscar Puts Steve McQueen Beyond Contemporary Art), but without his contribution, the contemporary art world would be poorer place. —CM

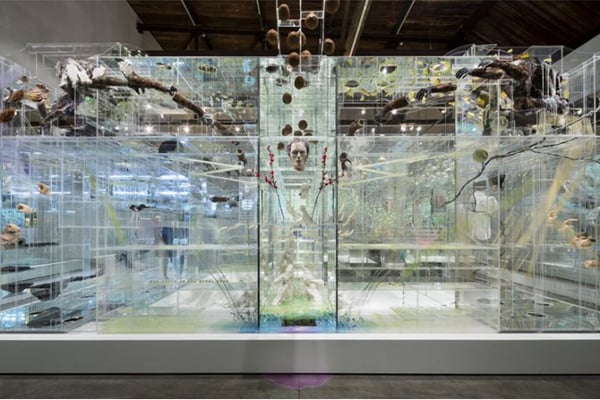

David Altmejd, The Flux and The Puddle (2014)

Photo: James Ewing, © David Altmejd

David Altmejd, “Flux” at Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris

Opened during FIAC, Altmejd’s major survey exhibition suggests that the artist’s best is very much still to come. Many of the works presented in the show, which will also travel to Luxembourg and Montreal, will be familiar to New Yorkers who have seen his last four exhibitions at Andrea Rosen. But, placing those works together has much to reveal. I was surprised at the extent to which Altmejd’s first series of large-scale vitrine-based installations from 2011 looked almost precious in comparison to the most recent work from that series, The Flux and The Puddle. The artist is engaging with a new level of grit, ugliness, and (despite their utterly bizarre mise-en-scene) realness in both his installations and his latest colossal, anthropomorphic sculptures. It’s work that you can look at for hours, continue to unpack, find new relationships to, and yet, importantly, never be able to piece together into a singular, cohesive whole. —AF

Gerhard Richter, Flow (2013)

Photo: © Gerhard Richter, courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery

Gerhard Richter at Marian Goodman, London

I’ve known Richter’s work for as long I can remember, but I don’t think I ever “got” him until seeing the tour de force that inaugurated Marian Goodman’s London location (see Gerhard Richter Triumphs at Marian Goodman London). For years, I had responded to the work of a highly intellectual artist in an intellectual way. I understood what he was doing, and why he was doing it, but I didn’t engage with it in a physical sense. Everything changed with this show, which charted an emotional trajectory through Richter’s recent work: from the stark, spiky glass sculpture at the entrance to the grey monochromes, and later, the psychedelic Flow paintings, culminating with the clinical precision of the Strip paintings in the upstairs. Illuminating. —CM

Volkan Aslan and Anne de Vries

Photo: Courtesy the Moving Museum, © CHROMA

Moving Museum Istanbul

The Moving Museum’s Istanbul edition was yet more proof that a solid selection of artists is worth more than any lofty curatorial concept (see: The Moving Museum Tears Down Tired Institutional Conventions). The energy displayed in the brand-spanking-new car park was contagious, sometimes literally (I came home with Jeremy Bailey’s You Museum banner popping up all over my computer). From Ben Schumacher’s ancient telegraph cables—presented as the relics of a communication revolution of yore—to Rafaël Rozendaal’s carefully weaved homepage structures of news websites, the works there felt like so many manifestations of my generation’s multifarious concerns: with the politics of the digital, the need to belong, and the uncertainties of what lays ahead. —CM

Yves Scherer, “Closer” (2014), Exhibition View Galerie Guido W. Baudach, Berlin

Photo: Roman März / courtesy Galerie Guido W. Baudach, Berlin

Yves Scherer, “Closer” at Galerie Guido W. Baudach, Berlin

Rarely have I come across an exhibition as timely as Scherer’s “Closer,” (see Has Post-Internet Art Come of Age?) from its tatami mat paintings and sculptures that speak volumes to the precarious experience of the permalancing creative class, to its 3D printed sculptures of Emma Watson, created by averaging the Internet’s vast image archive of the actress-cum-model. The show unravels the Silicon Valley mantra of technology’s ability to bring us closer to our friends and extended networks than ever before, when in fact the result is some mental approximation of closeness, which, while satisfying insofar as it makes connecting easier on some level, hollows out the experience on the whole. —AF

Philippe Parreno, Quasi Objects: My Room is a Fish Bowl, AC/DC Snakes, Happy Ending, Il Tempo del Postino, Opalescent acrylic glass podium, Disklavier Piano (2014)

Photo: © Andrea Rossetti, courtesy the artist and Esther Schipper, Berlin

Philippe Parreno, “Quasi-Objects” at Esther Schipper, Berlin

My 2014 art experience was bookended by Philippe Parreno. Days into the new year (and days before the exhibition’s close) I got lost in his unspeakably remarkable show at Paris’s Palais de Tokyo. As things wound down for the season back in Berlin, his first show in seven years with Esther Schipper, “Quasi-Objects” was equally fantastic. Conceived as “a self-reflective genealogy” of Parreno’s practice over the last 20 years, the show quotes heavily from Paris: Flickering Light (2013, a light installation controlled by the player piano in the gallery’s rearmost room) and Snow Drift (2014, a mound of artificial snow, diamond dust, and clay placed in an out of the way corner) make a reappearance. The exhibition continues Parreno’s investigation of what French philosophers Michel Serres and Bruno Latour have called quasi-objects, which deconstructs the subject-object binary, placing emphasis on the internationality between objects and the subject-hood they take on in the process of one perceiving that multi-object whole. Like most of Parreno’s work, it’s deeply theoretical stuff. But for “Quasi-Objects” he’s managed to make the esoteric accessible by resurrecting a piece, My Room is a Fish Bowl from 1997, which sees a dozen or so fish balloons float freely throughout the gallery. In the moment of humorous reprieve the fish give from the mental task of trying to unpack the exhibition as a whole, the entire point becomes clear. —AF