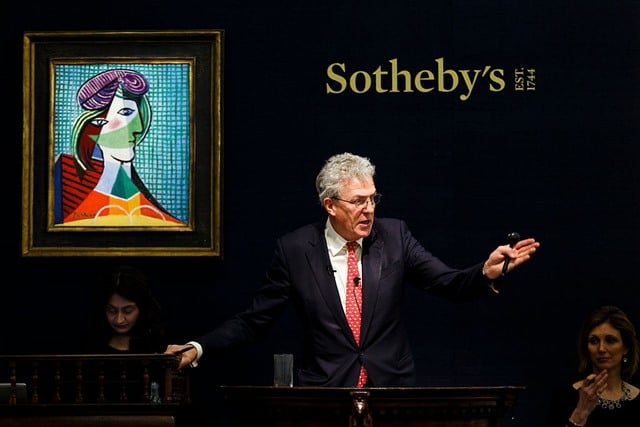

Auctions

Exodus at Sotheby’s Plunges Auctioneer Into Murky Waters

What will Sotheby's have to do to rebuild?

What will Sotheby's have to do to rebuild?

Brian Boucher &

Eileen Kinsella

There are a lot of empty offices at Sotheby’s right now, as one of the world’s principal auction houses sees a string of departures of high-level staffers. The unprecedented shakeup follows a losing battle with an activist investor, a change in leadership, and a pricey acquisition of an art advisory firm, and it puts the auctioneer in a dicey position just before one of its big sale seasons.

Experts talking to artnet News, mostly on condition of anonymity, characterize the turmoil at the auction house as unique in living memory, and say that while Sotheby’s will certainly live on, it faces difficult times ahead. This potentially rocky spell comes amid a slowdown in the global art market.

According to the recent TEFAF Art Market report, the global art market achieved total sales of $63.8 billion in 2015, falling seven percent year-on-year from the previous high of $68.2 billion. This marked the first decline since 2011. There’s also considerable uncertainty in any presidential election season, and this one is highly unusual, to say the least.

Sotheby’s was founded in London 272 years ago; if you total up the collective tenures of fourteen recent departures, some of them with the company for decades, the sum, 311, is more years than the auctioneer has been in operation. Those recent exits, too, follow the 2013 exit of Tobias Meyer, head of contemporary art worldwide, after two decades with the house.

Related: The Total Tenure of 14 Recent Sotheby’s Departures Is More Than the Age of the House

Alex Rotter and David Norman both announced their departures this year.

Photos: Patrick McMullan.

This results in losses of “deep pools” of institutional memory, says one insider. Some of those who have left had “unparalleled knowledge” of top-tier clients, one former staffer told artnet News. “The old art-collecting families, whose collections will soon enough be estates headed to market, will have no connection to the house,” a dealer said.

The house has “decimated” its strength in the Impressionist and modern art field, one dealer said. That realm has seen some of the highest prices ever paid for works of art—see, for example, the $170 million recently paid for a Modigliani and the $179 million for a Picasso.

And all eyes will be on York Avenue for the auctioneer’s May sales, which include its most high-profile and high-ticket events: the New York auctions of Impressionist, modern, postwar, and contemporary art. Auction houses typically finish tying up consignments for those sales during early March. (The house recently announced the consignment of a rare Francis Bacon, tagged at up to $30 million and a 1968 Cy Twombly blackboard painting, Untitled (New York City), which is estimated to take upwards of $40 million.)

However, some sellers, according to experts we spoke with, are very wary of entrusting their treasures to Sotheby’s in this time of unrest, which could further undermine the house in the short term.

As of March 28, the publicly traded company’s stock (BID) has fallen roughly 40 percent over the last year, from $42.40 to $25.15 per share. It dipped as low as $19.14, in February.

Proxy Battle, Buyouts, and Falling Stock Prices

Hedge fund manager Dan Loeb led a nearly year-long battle to gain greater control of the company, starting in mid-2013 and ending with victory for Loeb as the house expanded its board of directors to include Loeb and two others from the banking and corporate world. Loeb had argued in an SEC filing that a “cultural malaise” had taken hold at Sotheby’s. The house was earning less and less each year in commissions as a percentage of auction shares, and Loeb argued that Sotheby’s leadership was focusing insufficiently on the growing market for modern and contemporary art.

That drive on Loeb’s part is due to the fact that art has consistently generated the biggest totals of both Christie’s and Sotheby’s in recent years, even though Sotheby’s has many departments, ranging from automobiles to jewelry, rugs and carpets to stamps and watches.

Two months after Loeb won his proxy battle, the house announced a partnership with online auctioneer eBay, for the second time in its history; a previous effort at a partnership failed.

Less than a year later, Sotheby’s unexpectedly chose former Madison Square Garden CEO Tad Smith for its corner office after Loeb succeeded in forcing out Bill Ruprecht, who had been with the company since 1980 and had been president and CEO since 2000. Many in the art world wondered whether Smith, with his lack of art expertise, could possibly guide the company effectively.

In December 2015, the house told the Securities and Exchange Commission that it would buy out some 80 employees and take a $40 million charge in an effort to cut costs.

Amy Cappellazzo.

On the heels of that revelation, the house rocked the art world with news of the whopping $50-million purchase of Art Agency, Partners, an art advisory firm founded just two years previously by Christie’s veteran Amy Cappellazzo and art advisor Allan Schwartzman. In addition to the outright purchase price, the two, along with their partner Adam Chinn, got a promise of $35 million in performance bonuses.

Cappellazzo had worked at Christie’s for some 13 years, achieving the post of chair of the postwar and contemporary art department before leaving in May 2013. Schwartzman got his start as a curator at New York’s New Museum of Contemporary Art in 1977 and wrote about art for the New Yorker and the New York Times. He had been an advisor for 15 years when he joined forces with Cappellazzo.

Insiders say the move left many in-house experts at Sotheby’s feeling deeply alienated partly because they were informed of the purchase only days before it was publicly announced. Now they feel their expertise and hard work will result in greater profits for the newcomers.

“These things have to be handled delicately,” a dealer who once worked for the house said in a phone interview. “And it wasn’t handled delicately.”

Moreover, despite the pair’s expertise and long experience, the purchase price was met with astonishment among experts who talked to artnet News, particularly in light of cost-cutting moves, including the aforementioned buyouts. Additionally, it was recently revealed by Bloomberg that the pay package for Smith’s first year in office alone is worth $20 million.

“If I were a stockholder,” said one art advisor of the $50 million price tag, “I would be writing Dan Loeb the kind of nasty letters that Dan Loeb is infamous for, saying, ‘What are you doing, you idiots?’”

Insiders also say that the Wall Street mentality of people like Loeb and his new appointments to the board may not serve the house well in the art market.

“The art market is a psychological market with nuances that are beyond what people learn in business school,” said an art advisor with decades’ experience in the field. “It confounds what business people think will happen. It’s a relationship business. And they’ve taken out years of institutional knowledge that private equity guys don’t believe in.”

One unusual aspect of the AAP acquisition is Sotheby’s assumption of an investment fund that the company is running. A document filed with the SEC in late 2014 by Art Agency Partners, a “Notice of Exempt Offering of Securities,” describes AAP as a “limited partnership” incorporated in Delaware.

Boxes on the filing are checked for “Pooled Investment Fund,” and a sub-category of “hedge fund.” The document says the date of the first sale to investors was in December 2014, and under “Total Amount Sold,” lists $99,188,904. According to the filing there are 10 investors in the fund, though names are not disclosed, in keeping with confidentiality and non-disclosure agreements.

Adam Chinn.

A source close to the matter told artnet News that one investor sunk roughly $50 million into the fund, but there’s no publicly available financial data on how the hedge fund has performed. Sotheby’s insists it has done well. “The fund has provided investors with very attractive returns on their capital,” said one Sotheby’s representative.

In response to additional questions about the fund, including what type of saleroom notice might accompany a work being sold at auction from the fund, a spokesperson for Sotheby’s said, “In the event that any works from the fund were to be sold at Sotheby’s, the appropriate disclosures would be made.”

Prior to its acquisition, AAP had sold works through Sotheby’s, and may continue to do so, despite now being managed by the auction house, if the sale is in the best interests of its investors, Sotheby’s said.

An Exodus and a Flood of Résumés

Just some among the senior employees who have left the house in recent months are Melanie Clore, European chairman and worldwide co-chairman of impressionist and modern art, who recently departed after some 35 years; David Norman, vice chairman of Sotheby’s Americas, who exited after 31 years; and Warren Weitman, who was chairman for North and South America and had served the auctioneer for 37 years. The departures have also included longtime administrative staff such as Mitchell Zuckerman, who was executive vice president of global operations when he left after 27 years.

When A. Alfred Taubman bought the company in 1983, a market insider who worked there at the time told artnet News that Taubman told the staff the company’s greatest asset walked out the door at six each evening, and Taubman assured them that it was his job to make sure they came back in the morning.

“This is a one-hundred-percent departure from that mentality,” said the dealer.

“It’s the end of an era but in more than one way,” New York dealer Daniella Luxembourg told artnet News, saying she is confident in the auction house’s future. She worked for Sotheby’s for years before starting a partnership with auctioneer Simon de Pury (now an artnet News columnist) which was then bought by luxury goods magnate Bernard Arnault and merged with auction house Phillips.

She pointed out that when David Nash and Lucy Mitchell-Innes, then heads of the house’s New York postwar, contemporary, modern art and Impressionist art departments, left to start a gallery, the house promoted a young, relative unknown staffer named Tobias Meyer, who had been running the contemporary art department in London, to fill their shoes.

“He was a very young expert from Europe, and placing him in such a high position was not the evident thing,” she said. “When some people leave, others come in, and young, unknown faces can do fantastically well.”

Besides the addition of Cappellazzo, Chinn, and Schwartzman, the house has also brought on Marc Porter, who had been at Christie’s for more than a quarter-century and who will start in late 2016 (after a noncompete period is complete). He was chairman of Christie’s America when he left; his new title hasn’t been announced. And Cappellazzo and Schwartzman are doubtless fielding a flood of résumés, especially since insiders say another wave of departures are likely to come after the May sales.

But the house has, for the short term, bet heavily on Cappellazzo and Schwartzman’s business-getting capabilities.

“They’ve got to be like a magician pulling rabbits out of their hats or they will need to conjure a new job for Tad Smith,” Kenny Schachter, artnet News contributor and art dealer, said via email.

“Amy and Allan and Marc can’t be everywhere all at once,” a longtime art advisor said. “The specialists are everywhere. They do a lot of traveling to keep clients warm.”

Also among the new hires at Sotheby’s are some ex-Christie’s staffers, including two who had left to work at AAP, including Ed Tang, who left Christie’s last summer when he was running the popular First Open sale, and Charlotte Perrottey. Both are now vice presidents in the fine arts division. Another ex-Christie’s staffer is Elizabeth Sterling, who headed the American art department at Christie’s and assumes the same post at Sotheby’s.

Sotheby’s has made a few promotions in the contemporary department; Grégoire Billault has ascended to head of the New York department, and of Gabriela Palmieri to chairman of the department in New York.

New York art advisor Wendy Cromwell takes a long-term view, saying the house isn’t going anywhere and will emerge strong from an uncertain time.

“For the right people, this is an opportunity,” she told artnet News in a phone call. “Auctions are a necessity. They’ll rebuild strategically and the ship will right itself.”