Auctions

Record-Shattering Picasso Sale Is a Much, Much Bigger Deal Than You Think

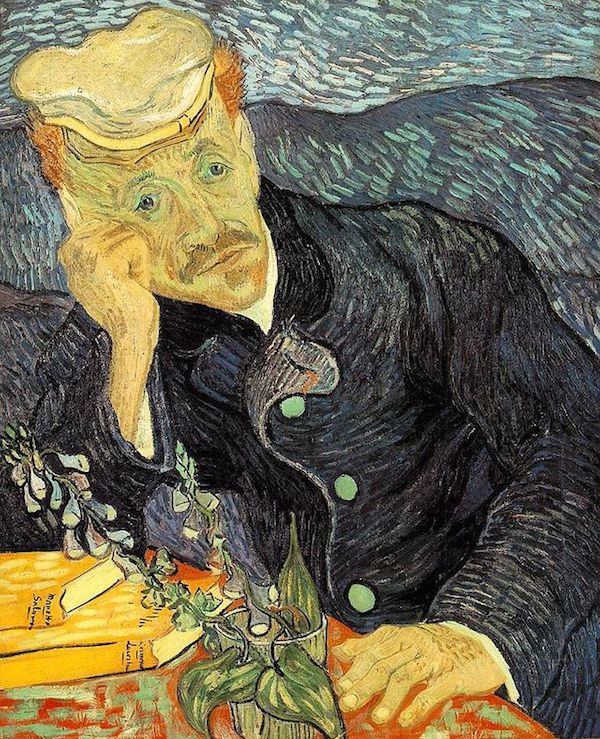

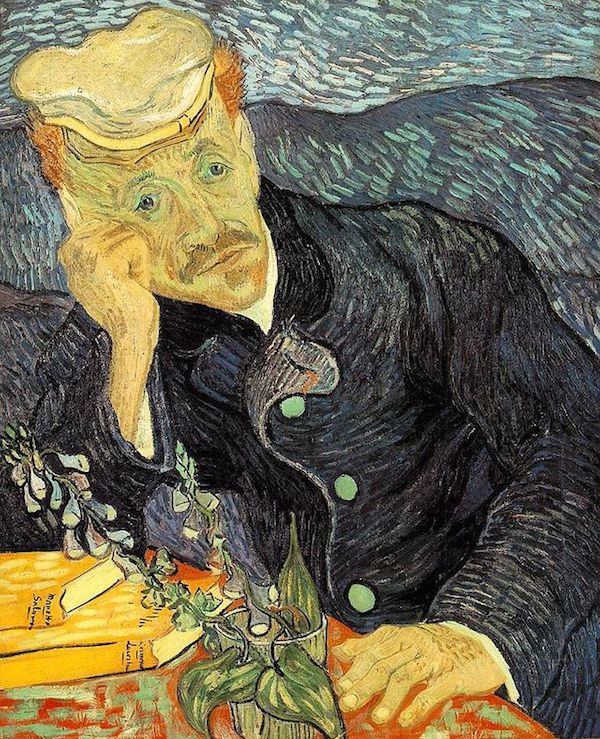

The sale surpassed even that of the Portrait of Dr. Gachet.

The sale surpassed even that of the Portrait of Dr. Gachet.

Ben Davis

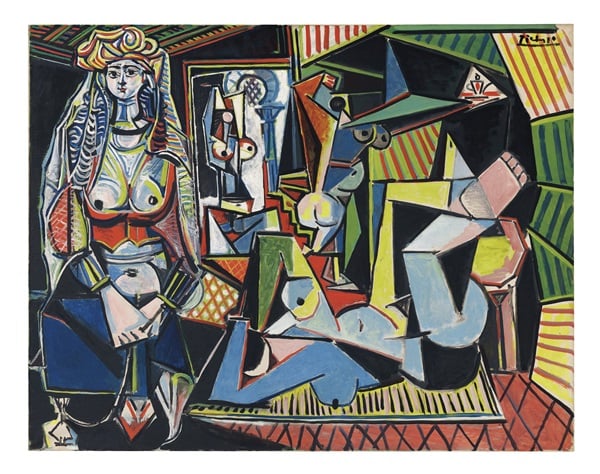

The $179.4 million sale of Pablo Picasso’s Les Femmes d’Alger (Version ‘O’), 1955, at Christie’s last week was greeted with the usual media frenzy, but I am pretty sure no one who was paying attention was truly shocked. A lot of the commentary focused on the mind-numbing sum as a symbol of inequality—but then inequality is the one stable fact of contemporary life.

Yet something remarkable did happen between the Picasso sale and the last auction-house record at Christie’s, the $142.4 million sale of Francis Bacon’s Three Studies of Lucian Freud in November 2013. To understand what exactly that something is, let me take you back to another time.

The year is 1990. In South Africa, Nelson Mandela is released from prison. Germany votes for reunification. Saddam Hussein invades Kuwait. Ice Ice Baby is a toe-tapping hit. Julia Roberts utters the immortal words, “You work on commission, right?”

And at Christie’s in New York, on May 15, eccentric Japanese paper tycoon Ryoei Saito pays $82.5 million for Vincent van Gogh’s saturnine Portrait of Dr. Gachet ($75 million, plus the house’s fee).

Pablo Picasso, Femmes d’Alger (1955), sold for $170.4 on May 11, 2015 at Christie’s New York

It was a staggering, record-setting sum at the time, a whopping $30 million over a high estimate which would have itself already placed it towards the peak of that era’s hypertrophic art market. The next night at Sotheby’s, Saito struck again, grabbing Renoir’s lustrous Au Moulin de la Galette for $78.1 million.

Huge as they are, such numbers probably strike today’s observer as rather prosaic. Then, dealers whispered about the possibility of a “$100-million painting.” Now, $100 million paintings are rare but anticipated, like an auction-room cameo from Leonardo DiCaprio.

But, then, in 1990 the average cost of a gallon of milk was just $2.78. Now it’s close to $4. That year’s Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles film fetched $135 million at the domestic box office. Last year’s far inferior Ninja Turtles movie fetched $191 million!

The point is, in inflation-adjusted terms, Portrait of Dr. Gachet’s $82.5 million would be the equivalent of over $148 million today. And that means that between Bacon’s $142 million two years ago and Picasso’s nearly $180 million last week, a new threshold was crossed.

Pierre Auguste Renoir, Au Moulin de la Galette (1876), sold for $78.1 million, on May 17, 1990 at Sotheby’s New York

Les Femmes d’Alger isn’t just the most expensive painting ever sold at auction. It is really the most expensive painting ever sold at auction.

The existence of inflation isn’t exactly an obscure fact (the good people at Wikipedia are on the case in their tally of the most expensive paintings), so I am not sure why this hasn’t gotten more attention in Christie’s official PR. I can think of two possible reasons.

Maybe emphasizing the existence of inflation makes all their other “records” immediately seem like a lot of hype, which is what they mainly are.

Or maybe, just maybe, the auction houses don’t want to be trumpeting the line of thought that the last time the market flew this high was just before an epoch-making global crash that it has taken us a quarter century to return from. It’s much better to talk about how collectors are “chasing masterpieces” or how its all about the fact that now “art is an asset class”—talking points, incidentally, that were also very much a fixture of the late-1980s chatter about the art market boom.

In any case, we are, as of last week, in uncharted art-market territory. Does the fact that this milestone has been passed mean that a red light should be flashing for observers?

I don’t quite know. In general, the answer, it seems to me, is to be found almost entirely outside of the auction houses: If the wealthy continue to get wealthier, the art market will thrive. That is, in my opinion, most of the story.

It is generally accepted that the 80s Impressionist and Modern boom was driven by Japanese wealth, created by a maniacal property bubble that was shortly to implode in a spectacular way, issuing in decades of stagnation for Japan. In 1990, the Bubble Economy was already coming apart, and at Christie’s, beneath the mega-lot fireworks, the art market was already showing signs of stress.

This does not seem to be exactly where we sit in 2015. Our global economy is riddled with contradictions—ask a Greek—but the rich are making out like bandits at the moment: Just today, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development released a report saying that the gap between rich and poor is at its highest point since their record-keeping began. In the auction room, the sound of champagne corks popping drowns out all worries.

What schemes are going on behind the scenes to keep it all together, we cannot know. The economist Nouriel Roubini (aka “Dr. Doom,” aka a “minor collector of contemporary art”) has made some headlines of late addressing the art world’s seedier side. “As I study and go to galleries and art fairs, I see that there is a lot of behavior that is shady at best,” he told CNN. “Some people use art as a form of money laundering…. Other people use money for forms of tax evasion…. The behaviors of the auction houses have become problematic.”

No one on the inside is going to spoil the party by dishing on such shenanigans now, with business booming. But as far as we can draw historical parallels between the two moments, we might just take the opportunity of Les Femmes d’Alger dethroning Portrait of Dr. Gachet to glimpse, through the lens of history, the kind of nasty business that might well be building up beneath all the happy talk about “new records.” (The Picasso was bought by a member of Qatar’s Al Thani family.)

Pablo Picasso, Les Noces de Pierrette (1905) sold for $51.3 million on November 30, 1989 at Binoche et Godeau, Paris

Here’s a long passage from Cynthia Saltzmann’s Portrait of Dr. Gachet: The Story of a Van Gogh Masterpiece, Money, Politics, Collectors, Greed, and Loss about the fallout from the 90s art crash in Japan. Perhaps it can serve, by proxy, to show what the practical implications of all that “chasing masterpieces” and the interest in “art as an asset class” can really be:

The most devastating scandal involved the Osaka trading company Itoman Corporation, which had used some 4500 million, much of it from its primary creditor, Sumimoto Bank, to buy thousands of paintings together with forged appraisals, which were then employed in an intricate black-market real estate investment program. For a while Itoman accumulated art at a fast enough rate to create a false sense that in late 1990 the art market was still appreciating. In the end, both Itoman’s president and Sumimoto’s chairman, Ichiro Isoda, resigned. As Japanese demand for Impressionist pictures evaporated, the country’s art imports plummeted from a high of 614.7 billion yen in 1990 to 22.9 billion yen two years later. Following the bankruptcies of numerous art dealers, Japanese banks and lending companies began taking possession of pictures. The banks also repossessed paintings from the entrepreneurs and professionals who had bought them with borrowed money, only to discover that in the current market they could recoup only 10 to 20 percent of what they had paid. In Tokyo and elsewhere, French paintings were stacked by the thousands in bank vaults and trunk rooms. Western art dealers brought in to scan the material advised against selling to avoid inundating the market. Reluctant to accept the humiliation of registering a loss, the banks held on to the pictures. Now bankrupt, Tomonori Tsurumaki, the racetrack owner who had squandered 8 billion yen ($51.3 million) on Picasso’s Pierrette’s Wedding via satellite, had reportedly in 1991 turned it over to creditors. (By 1997 art experts estimated the paintings taken by Japanese banks and lending companies to be worth as much as $3 billion.)

Fly high, fall hard.

On November 11, 1993, three years after his era-defining purchase of Portrait of Dr. Gachet, an ailing Ryoei Saito was arrested on bribery charges and stripped of his title as honorary chairman of his family’s paper empire. He had supposedly paid an official to open up an area of protected forest in order to build a golf course. It was to have been called “Vincent.”

Saito’s Renoir is believed to have been later discretely sold off at a private sale. It’s not clear where the Van Gogh ended up.