Analysis

Five Reasons Why Christie’s and Sotheby’s Day Sales Deliver Amazing Value to Collectors

You can learn a lot about the market from sales that don't make headlines.

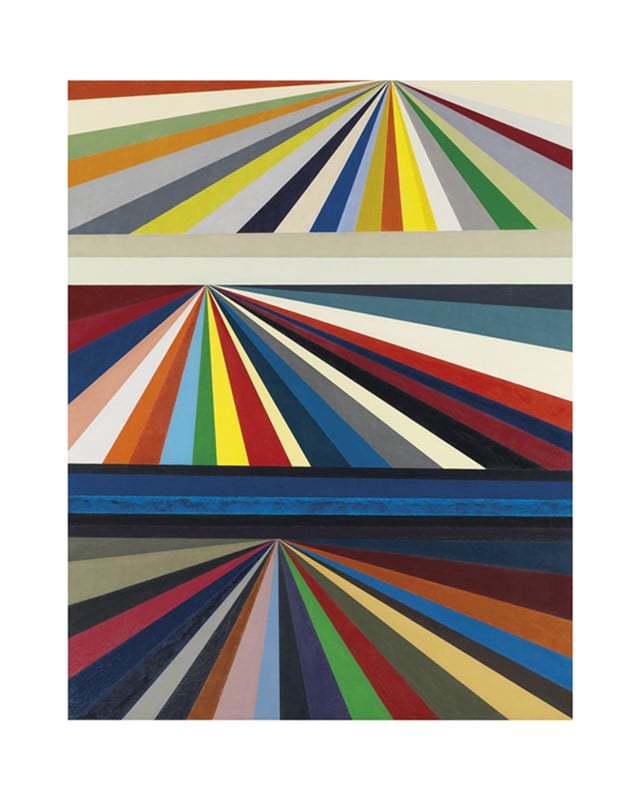

Courtesy Christie’s New York.

You can learn a lot about the market from sales that don't make headlines.

Brian Boucher

We’re in the thick of the second week of the two-week New York auction season, during which we’ve seen an Amedeo Modigliani sell for $170 million Monday night at Christie’s bringing in the second-highest price in auction history.

But what you don’t read about in the headlines are the more modest sales that take place during the day.

Christie’s New York alone is offering some 400 works at two sales Wednesday, which are forecast to total a little over $100 million. While these sales may not attract the celebrities, for some art dealers, it’s the meat and potatoes of their business.

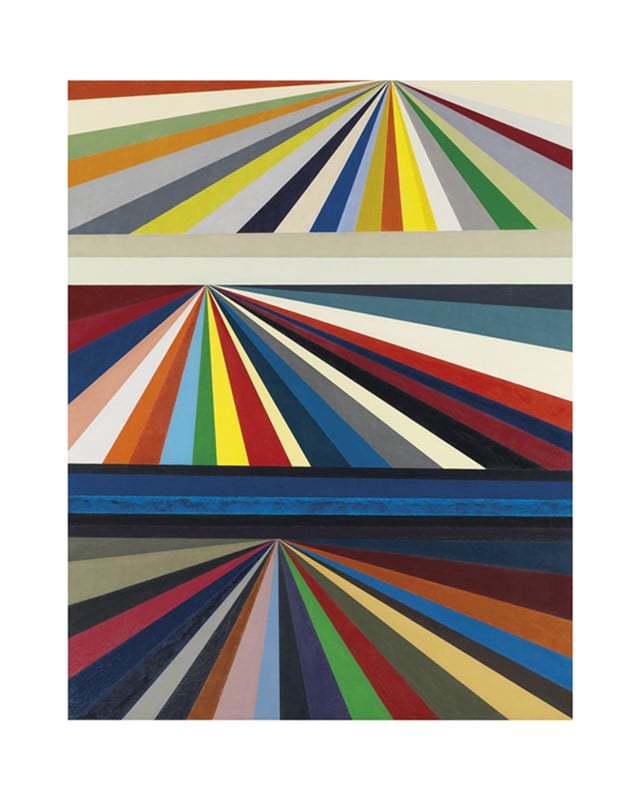

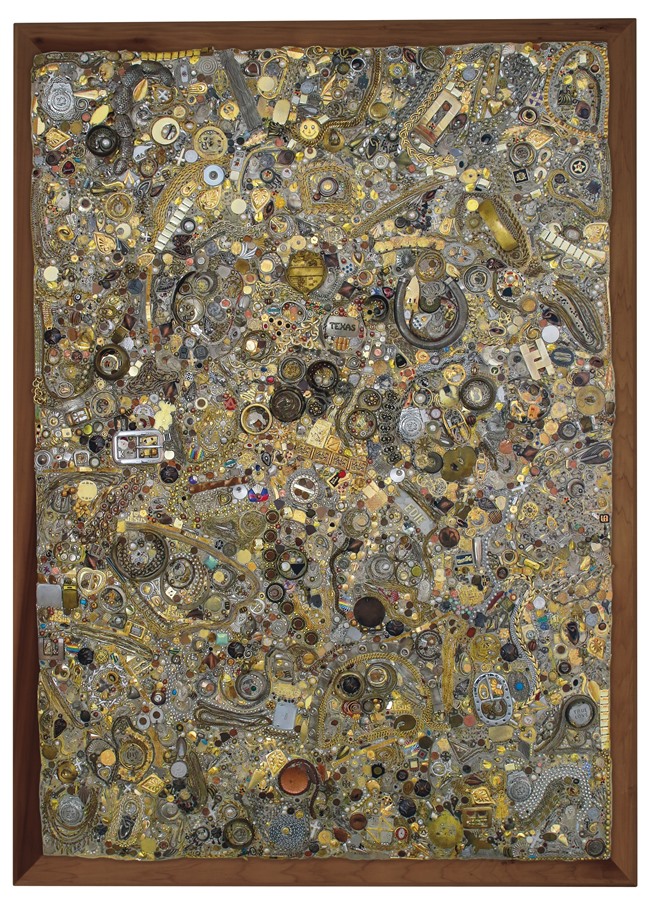

At the afternoon auction of postwar and contemporary art, estimates on the priciest works among the 175 on offer top out at a mere (!) $1.5 million, the high estimate for both Mike Kelley’s 2001 assemblage Memory Ware Flat #24 and an abstract, gray, untitled Christopher Wool painting from 2003.

Here are some of the reasons the professionals turn up at these sales, and why you might want to pay attention to them too. And unlike the exclusive evening sales, they’re free and open to the public, so sneak out and drop in one of these days.

Jeff Koons, Jim Beam—Box Car, 1986, stainless steel and bourbon.

Courtesy Christie’s New York.

1. This is where the houses make a lot of their profits

The auction houses vie for the newsmaking artworks, but they sometimes have to give away the shop to secure the consignments. When Peter Brant sold Jeff Koons’ Balloon Dog (Orange) at Christie’s New York in 2013, for example, as the collector later told the New York Times, the house waived the seller’s commission and then gave him “a large share” of the buyer’s fees. But that’s what they sometimes have to do to get the big (ahem) dogs.

Evening sales also often include a great number of works whose sellers are guaranteed a certain price, either by the house or a third party, and if that’s not met at the auction, the house can be on the hook. Works coming up for sale during the day aren’t guaranteed, so the house makes the full profit on the works with the fees they charge both the seller and the buyer.

2. Dealers can really stock up on inventory

Most gallerists don’t just make their money on what is hanging on their walls, but rather on works they’re re-selling in the back rooms. A former director at Jan Krugier Gallery told artnet News that he spent time scouring the catalogues of upcoming day sales and often snatched up works that people didn’t realize were great ones. The former director also said Krugier even used those big catalogues to create teachable moments for his staff, quizzing them on which lots might be the hidden gems.

Mike Kelley, Memory ware flat #24 (2001), paper pulp, tile grout, acrylic, miscellaneous beads, buttons and jewelry on panel.

Courtesy Christie’s New York.

3. These are more like actual auctions

The evening auctions, especially the high-profile contemporary art ones, are highly choreographed. The auctioneers know who is sitting where and who is interested in which works. Particular works are often guaranteed to meet a minimum price, which is not publicly disclosed.

Day sales, on the other hand, are more unpredictable and rough-and-tumble, and they move along quickly—works typically are on the auction block for about a minute apiece. There are no twelve-minute contests, like the fight over Edvard Munch’s Scream at Sotheby’s New York in 2012. You can see more unpredictable contests break out. “It’s more about finding a willing seller and a willing buyer in the moment,” said Citi’s art advisor Suzanne Gyorgy. “And since they’re not ticketed, they’re much more widely accessible.”

4. They give a broader view of the art market at a given moment

Since as many as 500 works might come across the rostrum in an eight-hour span, the day sales give a much wider view of what’s happening in the market. So these sales may give a more informative snapshot of the market’s ups and downs than the evening sales, which may have just 50 or 70 lots on offer.

5. You can find better deals

“You can find a real opportunity to get great works in the day sales,” said Gyorgy.

The cheapest works in Christie’s afternoon sale today carry estimates as low as $4,000. Yes, $4,000 for an untitled 1988 work by Meyer Vaisman, a 1980s art star who had a comeback show at New York’s Eleven Rivington (now 11R) in 2014. (Heck, that’s the checking account balance of a certain New York art critic we know.)

There are other works with estimates as low as $10,000 by artists such as Richard Artschwager, Mel Bochner, Susan Rothenberg, and Rosemarie Trockel. Bump that up to $30,000 and you might take home a Sol LeWitt or an Ella Kruglyanskaya.

Another art advisor told of works by Dan Flavin, Mike Kelley and Jeff Wall selling for fractions of what one would pay at the artists’ galleries.

Who says art is just for the super-rich?