Ari Emanuel, the Tinseltown star-maker and co-founder of entertainment megalith Endeavor, walked into Frieze Los Angeles at Paramount Pictures Studios on Thursday morning like he owned the place. That’s because he does own it. Endeavor bought 70 percent of Frieze in 2016, and at the end of this year, it has the option to buy the last 30 percent, currently held by original co-founders Amanda Sharp and Matthew Slotover.

Emanuel was not glad-handing art dealers and collectors. He was wearing old-school headphones, complete with clips that went around his earlobes, and the whole contraption was attached to his phone via a dongle connector. As he worked his way through the booths, Emanuel—immaculate in a polo shirt, white slacks, and pristine white sneakers—was making calls as if he were in his Beverly Hills office. “OK honey, I’ll take care of it,” he said into a tiny mic affixed to the tangled headphones. “OK. OK. OK. Yes, it’s done, OK. OK.”

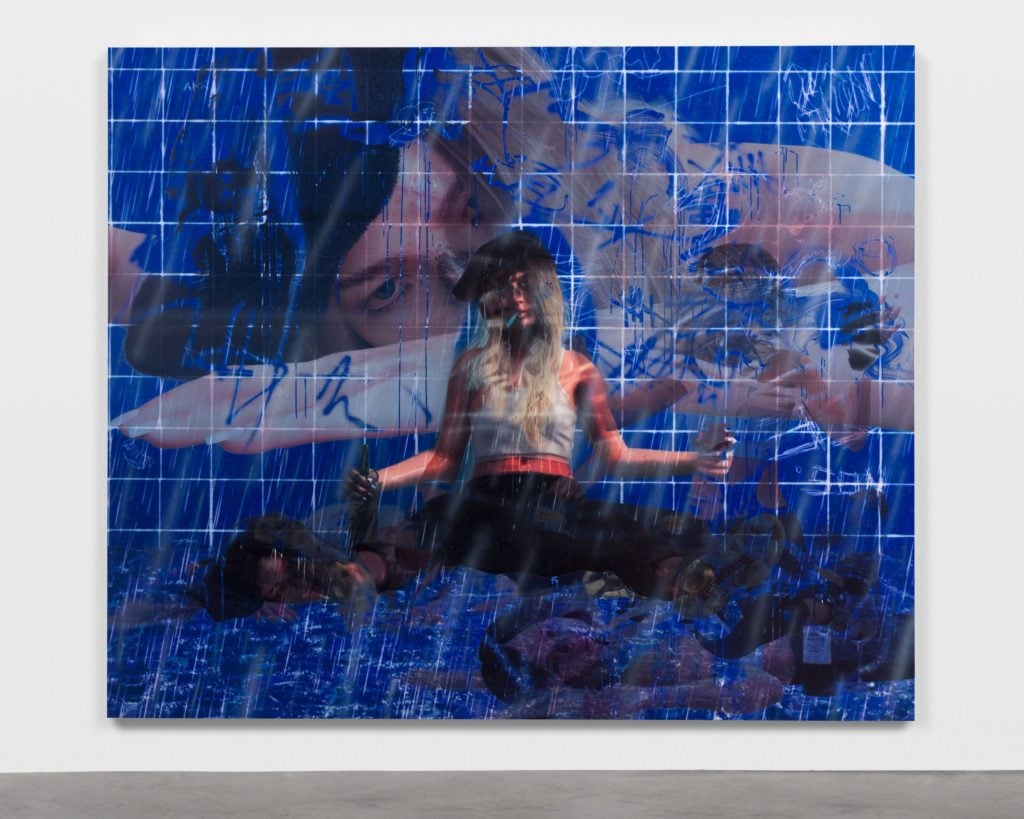

The Pit in the Focus LA section at Frieze Los Angeles 2020. Photo by Casey Kelbaugh. Courtesy of Casey Kelbaugh/Frieze.

An advisor led Emanuel toward the large Christina Quarles paintings at the booth of Regen Projects, but he quickly ducked out and made his way to the fellow local gallery Overduin & Co., all the while saying audible and inaudible things into his mic. At one point, he ducked into the Gladstone booth and was greeted by director Cooke Maroney (whose wife, Jennifer Lawrence, has notably been without an agency since she left CAA at the end of 2018).

But while it appeared that Emanuel, the inspiration for Ari Gold on the show Entourage, was just checking in on one of the corners of his empire—an empire that was wounded by the aborted Endeavor IPO last year—he was also there to buy. Frieze artistic director Loring Randolph told me later that Emanuel had purchased a large painting by Jordan Casteel from Casey Kaplan, which retail above $50,000. “That shows how embedded he is in all this,” Randolph said.

Star-Studded Buying

That sale was just one of the highlights of the second edition of Frieze LA, a fair that was pretty much universally praised by VIPs during the preview yesterday. After a rainy first edition last year, the art gods let the sun shine on an event that has managed to bottle the Hollywood Dream as best an expo can. The attendees were young, chic, and, more often than you would think, famous; that young woman who looked like the actress Lily Collins really was the actress Lily Collins.

And yes, that really was Leo DiCaprio talking to Brendan Dugan, the founder of New York’s Karma, checking out an Alex Da Corte. And that really was A-Rod and J. Lo chatting with Per Skarstedt about a Richard Prince painting. Kendall Jenner didn’t show up—but she did drop $750,000 on a James Turrell work, courtesy her advisor, Meredith Darrow, who bought it for her at the fair. Was that Usher? Yeah!

And if this phalanx of celebs didn’t make things surreal enough, the proceedings were all simultaneously reflected back out to the world on Instagram. Alex Israel, whose practice relies heavily on both the Hollywood origin story and its current selfie-addled state, was both at the fair (via his work) and in the fair (in person) posing for pictures and snapping them himself. (He also gave me directions to the Cha Cha Matcha stand, which felt like peak La La Land something.)

At one point, I was summoned by the omnipresent curator Hans-Ulrich Obrist to chat about the fair, as we do, but then got an eerie feeling I was being watched; I looked, and an assistant was filming our conversation, live-streaming it on Instagram.

I rolled with it. We were, after all, at a movie studio.

Leonardo Di Caprio photographs work by Avery Singer from Hauser & Wirth at Frieze Los Angeles 2020. Photo by Sarah Cascone.

Intoxicated by LA

All this star power—which the art world can pretend it doesn’t care about, but Instagram tells a different story—created a giddy feeling inside the tent.

“Right now, we’re at the center of the art world—it’s right here,” said Jeffrey Deitch, the art dealer who has long been an advisor to Emanuel and opened a spacious new Hollywood gallery around the time of Frieze’s first LA edition. “And to say that Los Angeles is the center of the art world, it’s incredible.”

Deitch has been one of the more visible figures during what’s now called “Frieze Week in Los Angeles.” (“We didn’t come up with that,” Sharp, the Frieze co-founder, shrugged when I asked her about the moniker.) The dealer opened a show on Saturday that drew 2,000 over the course of the night. At the fair, he sold works by Pat Phillips, Alake Shilling, and Theresa Chromati for between $5,000 and $28,000. And he’s become indispensable to budding collectors in the entertainment industry. Miley Cyrus was at the LA gallery for a personal walkthrough on Saturday, and as I approached the booth at Frieze, Deitch was speaking with singer The Weeknd.

The Weeknd at Frieze Los Angeles 2020. Photo by Sarah Cascone.

The dealer posited that perhaps this kind of intermingling can only happen in LA. “I’ve had a vision for a long time where I don’t observe the border between fine art and popular culture, art and music and film—I’m very interested in creative people who themselves blur lines,” Deitch said. “It’s a very connected community here.”

Frieze managed to successfully eventify the proceedings, making the experience feel more like being at Coachella than on the Messeplatz—especially in the New York backlot, where special projects and performances spilled out of fake apartment buildings and storefronts. But even if Frieze wants to position the fair as something other than a trade event, it still needs to please its exhibitors, and that means ensuring that all those celebrities and influencers and models in attendance actually, you know, buy art.

After last year’s slight hiccup due in part to the dismal weather (LA and rain do not mix), sales this year were solid, especially in the mid-six-figure range—though Gladstone sold a Keith Haring painting for $3.75 million, by far the priciest work sold on the opening day. Zwirner placed a very large Neo Rauch painting priced at $2 million, and Jack Shainman sold a major Barkley Hendricks painting and said, somewhat cryptically, that major paintings by Hendricks range from $1.5 million to $5 million.

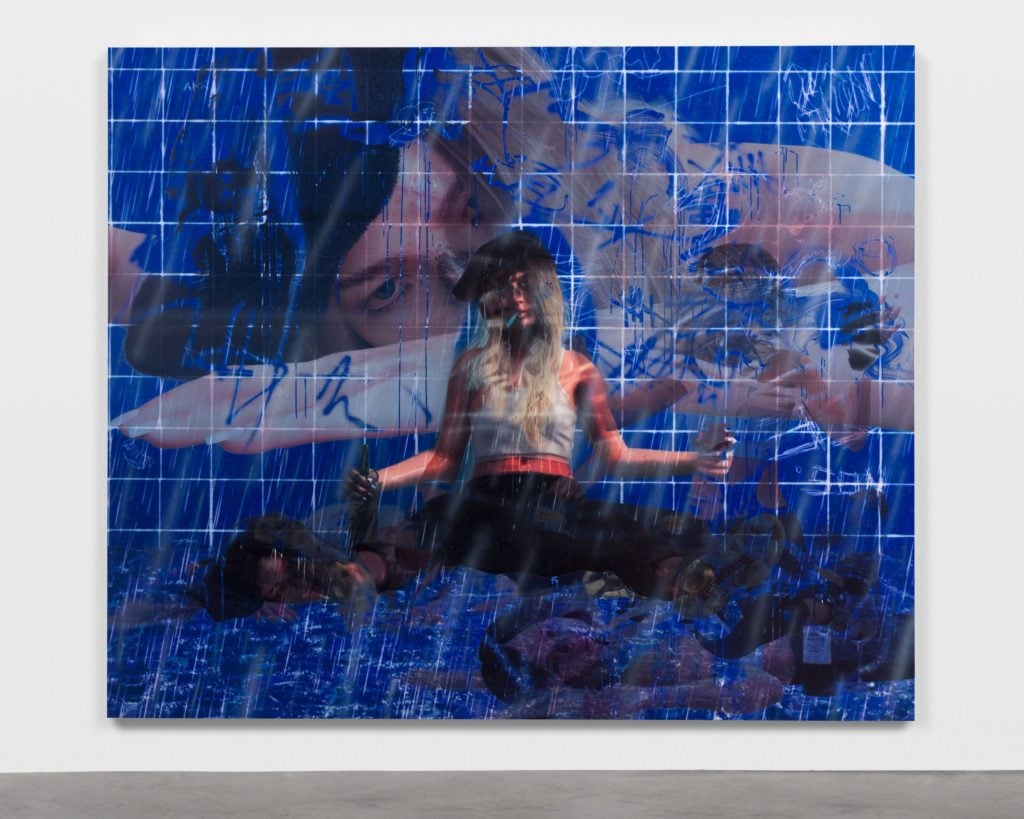

Avery Singer, Jordan, a new work making its debut at Frieze Los Angeles. © Avery Singer. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth, Kraupa-Tuskany Ziedler, Berlin

Elsewhere at the fair, local mainstay David Kordansky sold two works by Angeleno Jonas Wood for $500,000, and one work by Angeleno Mary Weatherford for $310,000. Jack Shainman sold Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s Seven Stitches South (2020) for $325,000, and London’s Alison Jacques sold a giant new work by Sheila Hicks for $550,000. All the Avery Singers at Hauser & Wirth sold for prices up to $495,000. Meanwhile, Metro Pictures placed works by Cindy Sherman, Camille Henrot, and Gary Simmons for as much as $150,000. Gladstone also sold a painting by Carroll Dunham for $650,00 to a collector based in Dallas through the advisor Benjamin Godsill. And White Cube sold a Julie Mehretu for $360,000, while Lehmann Maupin sold Liza Lou’s Shelter From the Storm (2020) for $275,000.

All this activity marked a significant uptick from the first edition. “Last year was a bust, last year was a total bust, because it rained,” Lisson director Alex Logsdail told me. “The organizers should not have had it rain, that was poor planning on their part!”

The other benefit of year two is a better understanding of what price point sells. Notably, the popular six-figure range here is a bit higher than at the larger Frieze New York fair, where sales have recently congregated in the five figures. But by the same token, Frieze LA may not be ready for Basel-style nosebleed prices. Last year, Logsdail said, Lisson “brought out A-game, and our A-game is a bit too expensive.” Now, “we’ve recalibrated and it’s great.” During the fair’s opening hours, the gallery sold 10 of the 14 works on its booth, including a mirrored Anish Kapoor for $700,000 and a 2019 Stanley Whitney painting for $350,000.

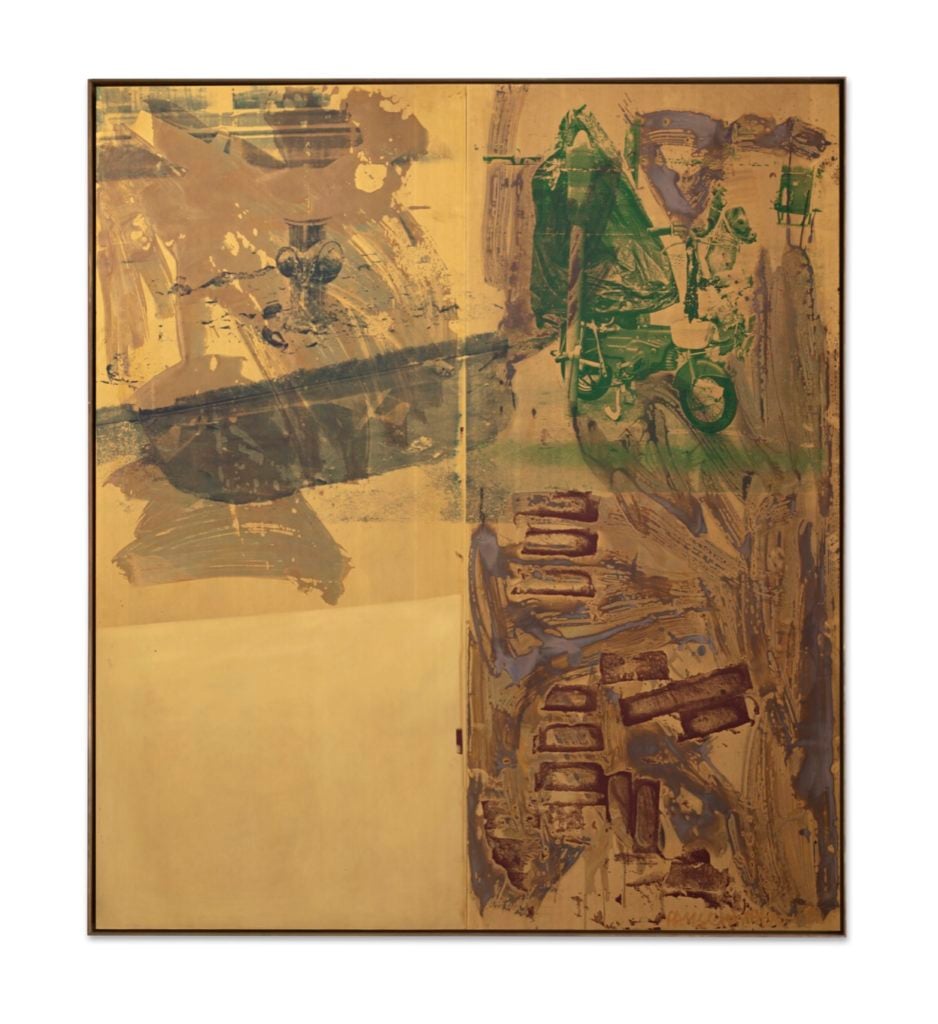

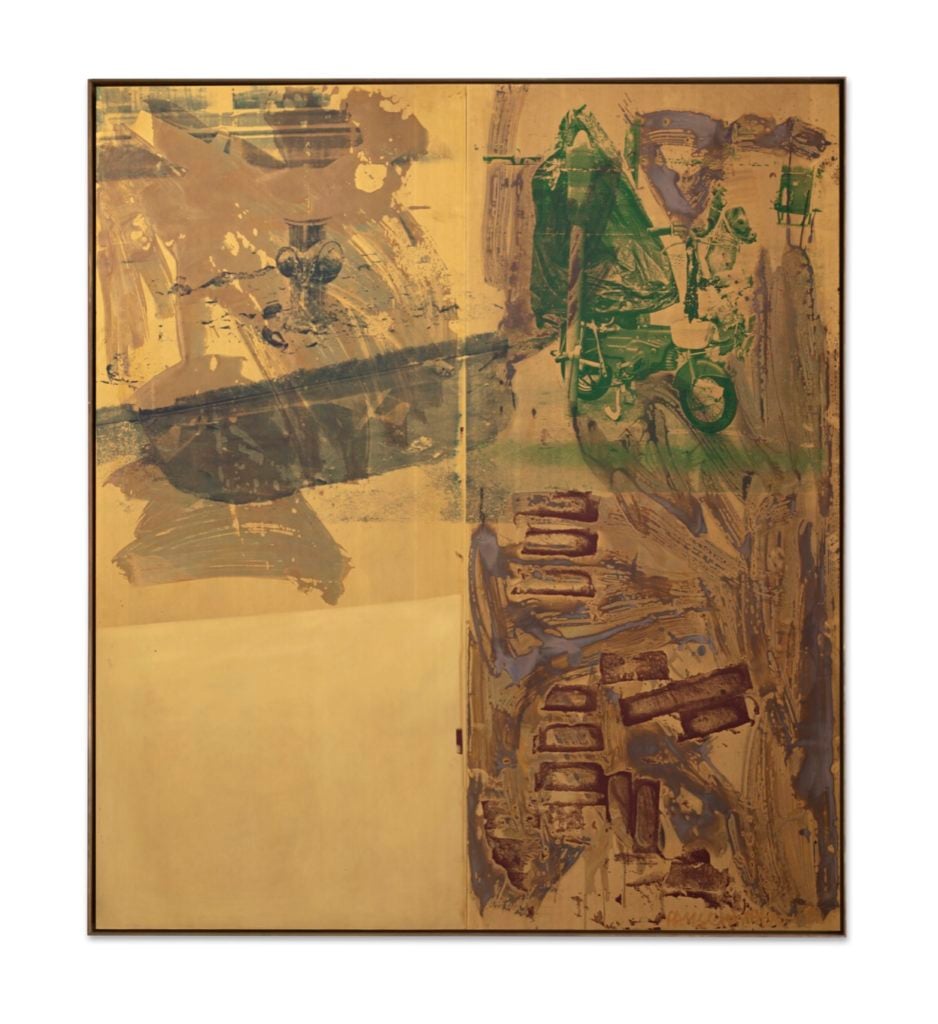

Thaddaeus Ropac also did slightly better than last year, and sold a work on the higher end of the offerings: Robert Rauschenberg’s Bowery Parade (Borealis) (1989) for $1.35 million. “Last year, someone said to me, ‘Oh, don’t bring expensive things, bring things less than $500,000,'” Ropac said. “We brought expensive work—and we sold it. There’s some of the best collectors in the world here. At Frieze New York, it’s expected that you bring young artists, but here, you bring important artists.”

Robert Rauschenberg, Bowery Parade (Borealis) (1989). Photo: Glenn Steigelman. © The Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, Adagp, Paris, 2020

(Perhaps the most-talked about sale of the day was of a work by a young artist, but it took place in London, where Amoako Boafo’s The Lemon Bathing Suit (2019), sold for $880,000 at Phillips on a high estimate of $65,000. The work was consigned by rabble-rousing LA collector Stefan Simchowitz, and when I ran into him at the Felix Art Fair—the rollicking event that also returned for a second go of it this year—Simchowitz said, “I have to pay my artists, so it’s all going to go to good homes. It’s not going to buy me a Ferrari.”)

Old Hollywood, New Hollywood

The fact that this city could have such a jam-packed art fair (not to mention the well-attended Felix) was kind of shocking to older LA lifers; Jonas Wood told me that when he first moved to LA in 2003, he was told: “Save your best stuff for New York.”

William Hathaway, the sales director at Night Gallery, has been working in LA for nearly two decades, and didn’t think a major fair could succeed in such a vast city that lacks a unified art district. “Fifteen years ago—no, I would never think this would happen,” Hathaway said. “The only time anybody came here was for the Oscars.”

Frieze LA’s director, Bettina Korek, attributed its success to a potent mix of factors, including a bevy of supplemental events and an eager audience. “A lot of people hoped that an international fair would establish roots in LA,” Korek, who will be leaving after this edition to become CEO of the Serpentine Galleries in London, told me. “The combination of the context and the timing—honestly I think Uber is helpful, it’s easier to get around LA.”

Installation view of Pace Gallery and Kayne Griffin Corcoran’s booth at Frieze Los Angeles at Paramount Studios. Photography by Flying Studio

Perhaps the best recipe for success at this new fair is to to follow the lead of Pace and Kayne Griffin Corcoran, who combined booths to show a series of works from James Turrell’s recent “Glass” series, glowing chameleonic orbs that light up whatever parcel of wall they inhabit. The gallery sold two elliptical works and two circular works—one went to Kendall Jenner, whose brother-in-law-Kanye West recently filmed an IMAX movie at Turrell’s masterwork, Roden Crater—priced at $750,000 each. (The works will raise money for the Crater, though collectors could also directly give money to the long-gestating artwork in the desert. Naming the amphitheater will cost you $36 million.)

It was the booth most evocative of the California ethos, the one that best distilled the spirit of LA—and of the fair, which sought to turn a pedestrian industry event into something bigger. “So much of painting is about how to deal with light, but this is light, and it’s about the thingness of light,” said Bill Griffin, the gallery partner who has worked with Turrell for decades. “This work exists in the art world, but it also exists in the world. It goes beyond white walls.”