South African artist Berni Searle’s installation for Frieze London involved getting naked and working with flour, leaving her signature bodily traces on the floor. When she arrived at the fair, however, she was dismayed to find the white tent at Regent’s Park already overrun with gallerists and art handlers doing their usual last minute tweaks. Needing privacy she couldn’t find, Searle opted not to complete the installation as planned for her South African gallery’s booth. The conditions, she thought, were not were not quite right.

Difficult conditions, as diverse as they may be, are what bind the eight female artists on view at Frieze’s new special section “Social Work.” The monographic presentations include Helen Chadwick, Mary Kelly, Ipek Duben, and Searle, among other politically-minded female artists who emerged in the 1980s and ’90s. Each of them, in individual ways, has been challenging the status quo of their time.

In a year that has been marked by further transformations in the #MeToo movement and revealing reports confirming a suspected gender gap in the arts in several cities in Europe, it is, as Stella-Sawicka says, “absolutely the right moment to be looking at these artists.”

By focusing on artists who emerged in the 1980s and early ’90s, their individual galleries build a picture of a powerful generation of feminism through distinct monographic shows; the hope is to shine further light on women who the market has largely overlooked in favor of their male contemporaries.

Helen Chadwick at Richard Saltoun.

Marketing Visibility

Last year, curator Alison M. Gingeras’ section “Sex Work: Radical Politics and Feminist Art,” which focused on explicit art by women from the 1970s and ’80s, received critical acclaim. In turn, Frieze director Jo Stella-Sawicka says a follow-up presentation looking to more contemporary and diverse perspectives on feminist discourse felt like a natural progression.

Notably, all the artists on view at “Social Work” are over 50 years old. Despite their individual accolades, it’s stunning to learn that at least four of them are presenting at Frieze London—or any fair—for the first time. It’s a testament to the weaker position that female artists have historically endured in the art market.

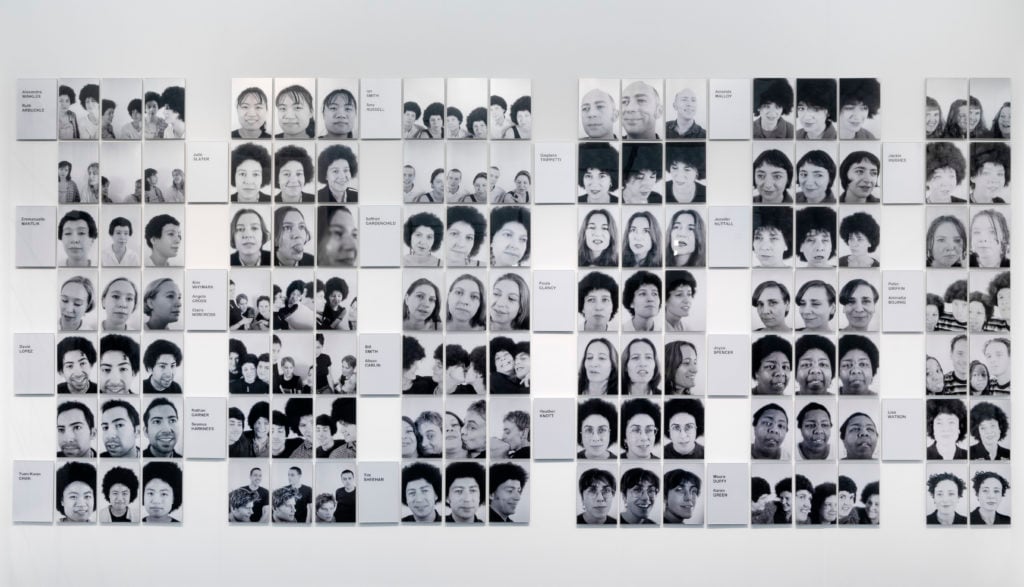

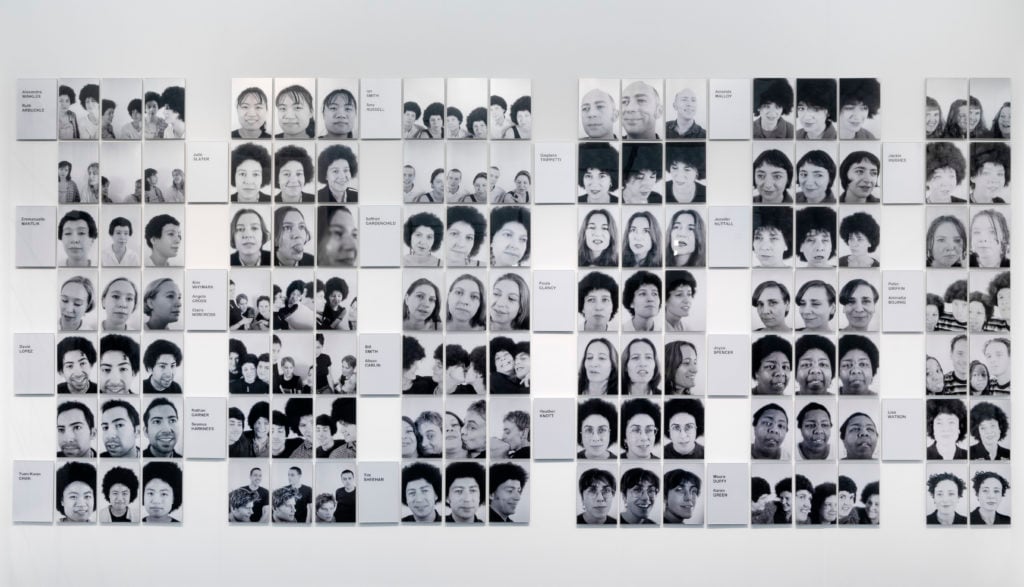

For London-based Sonia Boyce, that visibility turned into fast results. By the end of preview day, it was confirmed that her 1997 photo installation, The Audition, has been acquired by Tate for this year’s acquisition from the Frieze Tate fund. (Two hundred of the 900 individual images that comprise the piece are on view at Apalazzo Gallery.)

“For this to go into the national collection 20 years after it was made is incredibly gratifying,” says Stella-Sarwick. She emphasizes that one of the section’s purposes is to consider the particular relationships between women artists and the British art market.

But what may appear as an increase in visibility—awareness of gender disparity as an issue has indeed evolved since these women started out 30 years ago—the hard numbers tell a bleaker story. Just last year, Freelands Foundation released a large study on the staggering gender gap in Britain: In 2017, just 22 percent of solo exhibitions in major London non-commercial galleries were by women artists. And that is not the worst of it: “The alarming data shows that women’s visibility in galleries and institutions is on the decline. Women are being seen less,” the study found.

Sonia Boyce The Audition (1997) was acquired by Tate. Courtesy Apalazzo Gallery.

Female representation by commercial galleries in Britain hovers around 28 percent—but it actually fell between 2016 and 2017. Stella-Sawicka explains that, unfortunately, there were many artists on the shortlist who could not be included because they don’t have any gallery representation at all. “Part of the job of this section is to focus on galleries who support these kinds of artists,” she says.

All this hinges on another hope: that the financial success of such a section may signal to other galleries that older female artists are, in fact, a profitable investment. “We have dozens, if not hundreds, more on the list that could inform a giant survey exhibition,” says Fatos Üstek, director of the David Roberts Foundation and one of 10 women on the all-female panel.

But the complex issues around visibility are tied to many conditions beyond gender politics in Britain. This is made especially clea in Searle’s experience in South Africa’s contemporary art scene. The marginalization that she experienced was predominantly based on her race rather than her gender, she points out.

At Frieze, the artist has presented eight luminous photo works as self-portraits called Still. In these images, Searle is naked and kneeling, working to knead white flour, which brings her dark skin color into focus. She explains that, though the labor of kneading is indeed a comment on women’s work, Still is about teasing out the difficult issues of racial representation in South Africa. The work, which dates to 2001, was made the same decade that cultural boycotts of apartheid South Africa come to an end.

Berni Searle Still (2001). Copyright Berni Searle. Courtesy Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg.

Body Work

The title of this year’s special section in some ways aligns more closely with last year’s display than with the works currently on view. Rather than speaking to “social work,” most of the artists on view have put their own bodies at the core of their artistic practices, as a platform for political and social engagement.

London’s Richard Saltoun has presented a compact survey of Helen Chadwick’s works, including an early photo-based series called In the Kitchen (1977), which depicts the artist dressed cheekily in costumes resembling kitchen appliances. These works have become rather important markers in the contemporary history of feminist art. (By the end of preview day, the series had almost sold out.)

“The body was paramount for Chadwick,” says the gallery. “But it wasn’t the body as female, it was the body as female and male, or hermaphroditic.”

Other works on view, like three prints in circular frames featuring flowers that resemble oversize orifices, are notably genderless. On the wall across from them, a pair of fur “paintings” are shaped like female genitalia. One states “adore,” the other “abhor”—a reference to society’s mixed-up messages about female sexuality.

Helen Chadwick at Richard Saltoun. Copyright the Estate of the artist. Courtesy of Richard Saltoun Gallery.

Next door at Pippy Houldsworth, conceptual artist and prominent feminist Mary Kelly’s work presents another perspective on the female body: that of self-image. Corpus was made directly after the artist finished her most famous work, Post-Partum Document (1973–79), a psychoanalytic treatment of motherhood through material evidence. In the early 1980s work on view at Frieze, Kelly says she was exploring the issues of self-value and self-image that arise after motherhood.

“What happens when you pass the reproductive moment?” asks Kelly. In the text-based pieces, she chronicles stories about getting older as a woman. The works’ reflective surfaces are intended to make sure the viewer sees themselves when reading her texts. Pioneering performance artist Joan Jonas was among those whose stories are chronicled in some way across Kelly’s panels.

“Unlike Post-Partum Document, [Corpus] was not a scandal, but it was a center of debate,” Kelly recalls. “There was collective discussion and intense engagement around the work. It’s my work, but there is a very collaborative background to it.”

Mary Kelly, Interim, Part I: Corpus (1984-85) Courtesy artist and Pippy Houldsworth Gallery. Photo by Ben Westoby, copyright Mary Kelly 2018.

Beyond Social Work

When asked what “social work” element binds the artists together, Stella-Sarwick points to their active roles in education. To give just two examples, the now-deceased Chadwick taught prominent artists like Sarah Lucas, Tracey Emin, and Gavin Turk, while Berni Searle is a professor at Cape Town’s Michaelis School of Fine Art.

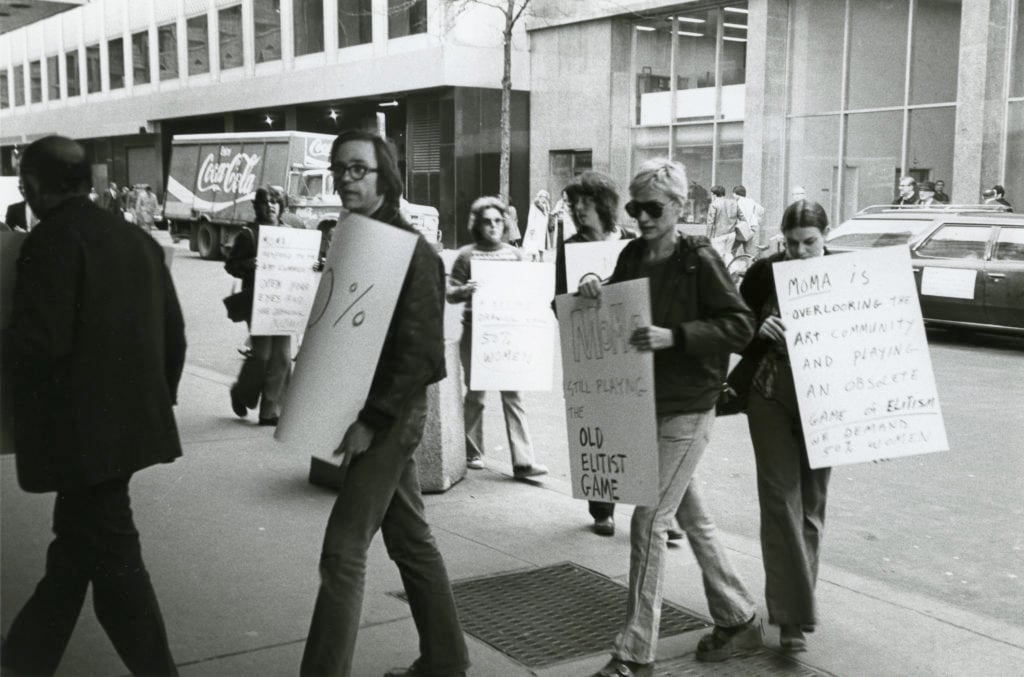

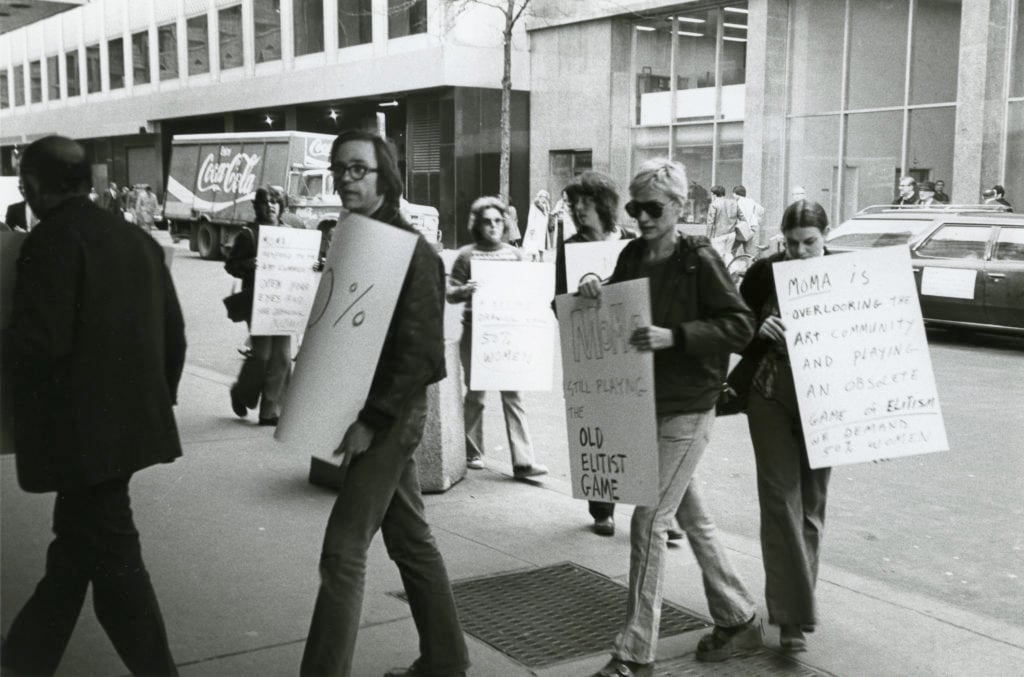

But these educational roles are also clear through their political or social activism, which also figures directly into their art. On view at Galerie Lelong, Nancy Spero’s work from the mid-’80s provides a critical look at specific countries, like South Africa or El Salvador, where citizens were oppressed by their governments. She remained politically active at a local level in New York City, where she lived until her death in 2009.

Nancy Spero protesting at the MoMA in 1976. Photo by Mary-Beth Edelson. Courtesy Galerie Lelong.

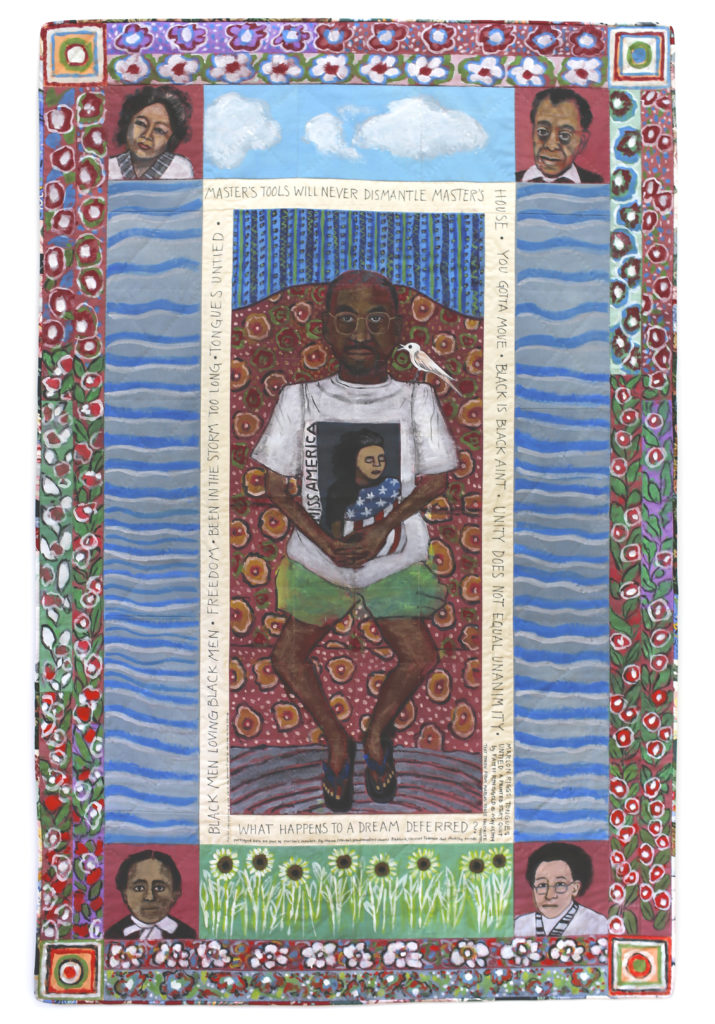

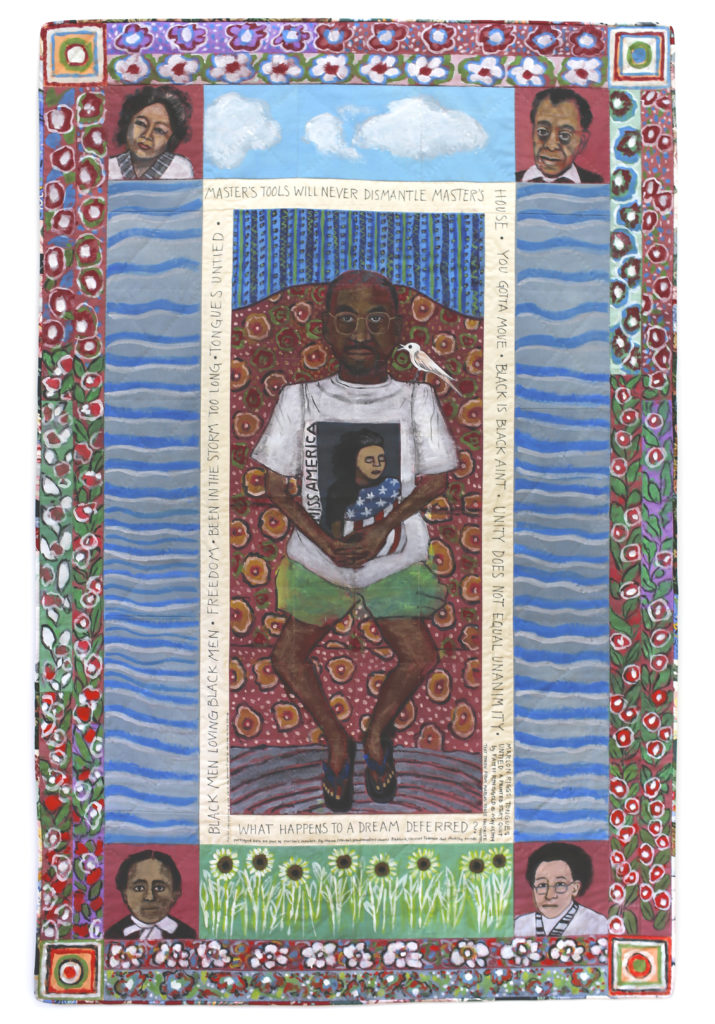

Another striking example was clear at Weiss Berlin’s presentation of Faith Ringgold’s “story quilts.” The incredible works on view range from her earliest in the 1970s to more recent pieces. Most striking is Marlon Riggs: Tongues Untied, a commemorative piece in honor of the black and queer American filmmaker who died from AIDS a year after they met in 1994.

Directly on the quilt, Ringgold has written “black men loving black men”—a radical idea of romance at the time. Weiss Berlin says that Ringgold worked with the medium in part because she had limited access to materials and space for storage; with quilts, she could simply roll them up when she needed to move. ACA and Weiss Berlin sold one work to a museum. (They are not releasing sales figures, but the works are priced between $160,000 and $500,000). The 87-year-old will also have a solo exhibition in summer 2019 at the Serpentine Galleries.

Faith Ringgold’s Marlon Riggs Tongues Untied (1994). Courtesy Weiss Berlin and ACA Galleries.

For many of these artists, though, there is still a ways to go. “The reality is that there is still a need to bridge the gap and give more recognition to artists from around the world,” says Serpentine curator and panelist Amira Gad.

“These artist were, by and large, operating outside of the mainstream,” says Stella-Sawicka. “The mainstream was incredibly conservative at that time.”

The next few days will tell whether the visibility will truly translate into market viability for these artists—but Frieze VIPs were proving highly responsive, at least for Chadwick and Sonia Boyce. “The ‘Social Work’ section at Frieze is attempting to expand our reception of art history, through concentrating on its strong female voices,” Üstek says. “It is through the multiplication of voices and positions we can achieve a better world.”

İpek Duben, Sherif (1980). Courtesy Pi Artworks.