Galleries

Anthony Haden-Guest on Garner Arts Center’s Stroke of Genius

It's a combination of obsessiveness and sheer peculiarity.

Image: Courtesy www.luis-bruno.com.

It's a combination of obsessiveness and sheer peculiarity.

Anthony Haden-Guest

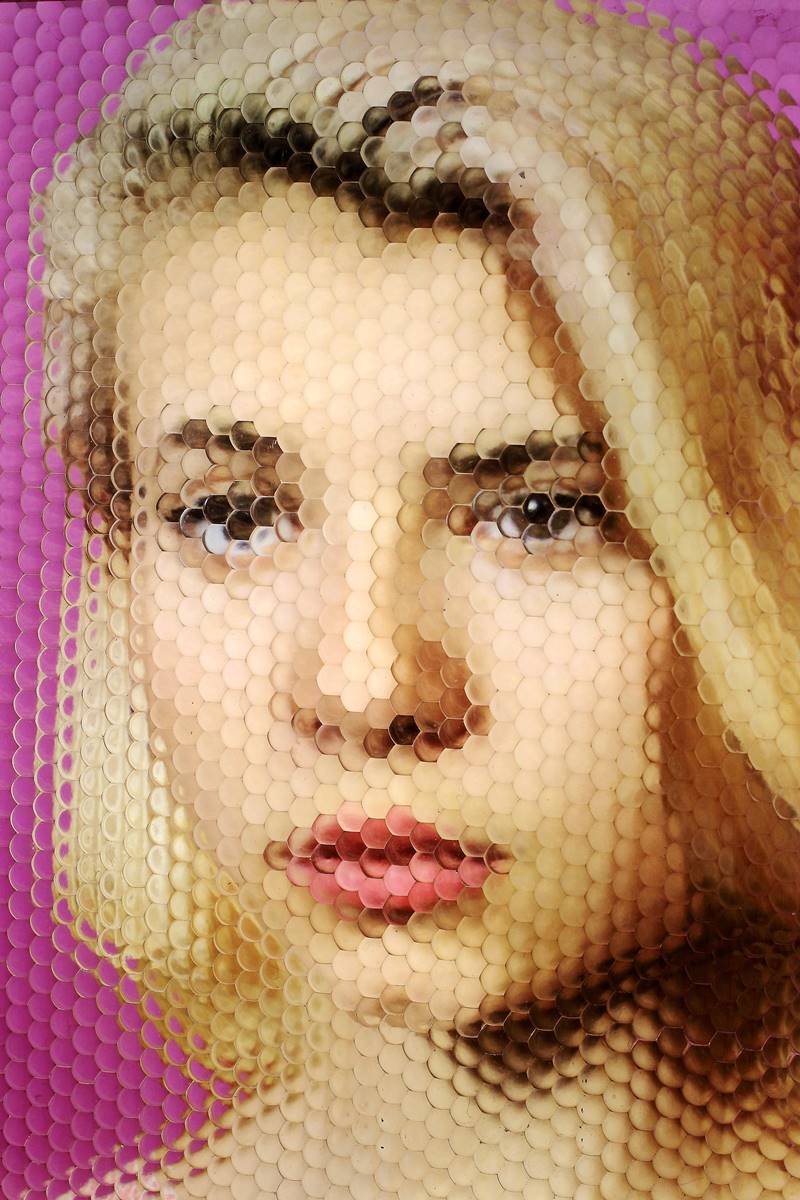

M. Henry Jones, Nico.

Image: Courtesy luis-bruno.com.

Foxes, coyotes and raccoons survive the destruction of their habitats by exploring suburbs and cityscapes and it’s no news that New York’s beleaguered bohemians are also being desperately inventive. Detroit and Los Angeles are favored destination cities but, more locally, there has been a fresh bohemian influx into such upstate townships as Woodstock, so I was perhaps more startled than I should have been while driving through Livingston Manor, a sedate hamlet up in the Catskills, to lay eyes on a guy who looked—black attire, full arm tattoo, piercings—as if he had walked straight off Avenue C.

Robert Parker, Stargazing.

Photo: Courtesy Margaret Bazura.

But it fit. M. Henry Jones, the photographer and animator, was driving me to a show of sculpture by Robert Parker, a one-time ornament of the Lower East Side, the Rivington School. Their cheerfully illegal sculpture garden, which had been regularly torn down by the city, is now history, though some of Parker’s marvelously gnarly ironwork still survives on the streets of the Lower East Side, and in Livingston Manor, where he now lives.

He too had spotted the tattooed fellow and disposed of his LES mystique. “I’ve heard him on his smartphone,” he told me. “He’s a bond trader.”

Rachel Amodeo, Air Fairy (Detail).

Photo: Courtesy Margaret Bazura.

That was a couple of months ago. Now the work of Parker, Jones, and another Lower East Sider, Rachel Amodeo, are in Something’s Out There, a show in another township, Garnerville, also upstate, in Rockland County. It is here that Jonathan Shorr, a Manhattan art dealer for twenty years, most recently from a space on Crosby Street, has recently established Garner Arts Center in a wondrous Early Industrial brick building, a former dye works, built in 1830.

If this show has something of a family feel, it’s not because there’s any resemblance in the work, but because these three artists are true to their Lower East Side roots. They make their work as if the rules of the art world game do not in any meaningful sense exist. In this outlook, they represent an outsider element for which the art world is hungry.

Parker’s rigorous iron works, which could be described as Funk Minimalism, are on the ground floor. Here, Amodeo has a room full of images, objects, collages, works in which she frequently uses dolls both as story elements and as art materials, but which, each from each, differ remarkably in their making.

M. Henry Jones, Flying Slatherpuss, (1999). Stroboscopic Zoetrope.

Photo: Courtesy luis-bruno.com.

The upper floor of the 8,000 square-foot space is occupied by Pushing the Optical Envelope, the defining subtitle of Jones’s work. Jones—he is politely insistent on the M—is an artist/inventor/tinkerer in his 50s who grew up in Buffalo, and worked at Artpark, the outdoor arts festival, in his teens. Artists whose projects left a lasting imprint included Gordon Matta-Clark, who sheared a building into nine segments with a power saw, Laurie Anderson, dueting with a playback tape on an electric violin, and Dennis Oppenheim, who impressed giant thumbprints on a parking lot.

His future direction determined, Jones came to Manhattan in 1975 with a scholarship to the School of Visual Arts, where fellow students with whom he became friendly included Peter Zaremba, front man of the Garage Rock band, the Fleshtones. Jones’s first New York animation was a self-portrait, assembled from still photographs, which shows him crossing a road. It was Zaremba who suggested a more ambitious project: an animation of a Fleshtones performance of a Lou Reed song, Soul City.

Soul City is one of those special handiworks—like the Chrysler Airflow automobile of 1934—which can be said to occupy a niche in art, design and tech history too. Jones made this 2 1/2 minute animation by hand-cutting 1,700 individual photographs with an X-Acto knife, adding color to each, and reshooting the segments frame by frame against a constantly changing background.

Just three years later, of course, this Analog Age hard labor would be rendered obsolete by the coming of MTV and a decade later it was, Hello, Photoshop! That said, Jurassic technology, first human efforts to solve a problem, have a special look. 19th Century ironwork, the first space modules, early Ferraris and Bugattis are not ridiculous compared to their sleek progeny, just different. So with for Soul City. The takeaway is that Jones’s arduously made cut-outs have now been swallowed up into that ever-hungrier ecosystem: The Art World.

M. Henry Jones, Animating Billboard, (1997).

Image: Courtesy luis-bruno.com.

Pushing the Optical Envelope, is at once folksy and hi-tech, unpushily ambitious. Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia would have blessed it, I imagine, and Rube Goldberg too. Jones’s childhood preoccupation with animation was followed by a broader exploration of techniques employed to create images, beginning with those that budded between the coming of photography and the birth of the movies, like the zoetrope, the praxinoscope, the kinetoscope, and moving on to later developments, such as lenticular photography and holograms. Most recently Jones has been using Fly’s Eye lenses to make 3-D portraits.

Here in Garnerville are early defining pieces, like Soul City, and such fruits of his more recent activity as 3-D portraits of Jim Jarmusch, Robert Frank, June Leaf, and Boonsri Dickinson who, back in Jones’s place on East 9th Street, introduced me to that techie supernova—both in intensity and duration—Google Glass. Here too are Jones’s giant wheels, which focus the eye on a single image. These are usually drawn by Jones himself in a cartoon-like manner which is wholly his own, and does not reference the increasingly mundane vocabulary of superhero graphics. The content can seem dark. On one of wheels a pig morphs into an alien, which turns into a girl, Molly, who turns into a duck, and so back into a pig.

There are also sculptures cast in resin of favorite Jones characters, like Snakemonkey, and Slatherpuss, a creature he encountered in a long ago dream, name and all, and who has wings, protuberant eyes and an orange beak. Or Killer Baby, an animated sculpture he created on a stroboscopic zoetrope. This is a representation of an infant, wielding a knife, and apparently yowling, who is viewed on a black hooded screen. But the world of Henry Jones is not creepy. He is a sweet-natured fellow, indeed abnormally so, and his work doesn’t have that slight resonance of the sinister you can even pick up from most cartoony art, even Disney. What it does have is a combination of obsessiveness, sheer peculiarity and an appetite for work that suggests a touch of that over-used word, genius.

Garnerville is just 45 minutes from Manhattan, and the culture which has nourished Jones was well represented. Frankie Infante, the guitarist with Blondie was there, as were Leonard Abrams, formerly the publisher of the East Village Eye, Keith Patchell, the composer, Esther Regelson, who wore the animation camera, and the poet/performer, Gabriel Don. Also Marc Miller, a notable dealer in ephemera from that culture, and others, and Mark Brady, a cinematographer on What About Me? Likewise Maria del Greco, the photographer, and Margaret Bazura, who worked with the Rivington School, and created the virtual reality experience for the show. Peter Zaremba sang, and he was backed on the guitar by another of the Fleshtones, Keith Streng.

The show will be up until April 17. Go!

“Pushing the Optical Envelope” is on view at Garner Arts Center from March 15-April 17, 2016.