Every Wednesday morning, artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, taking the long view…

RUNNING IN PLACE

If you’re a numbers hound like me, then you may have spent the past three weeks poring over the latest editions of multiple data-driven reports on last year’s art market. Overall, the dominant theme has been the trade’s strong resilience after a pandemic-disrupted 2021. But while the recovery looks impressive from up close, the temptation to focus on the market’s performance since just before COVID obscures a larger finding. Despite plenty of talk about innovation and democratization, overall art sales have been stuck in neutral for about a decade—no matter whose methodology you rely on.

You can see it in the spring 2022 issue of the Artnet Intelligence Report (if you’re an Artnet News Pro subscriber, that is). Global auction houses tracked by the Artnet Price Database sold $16.6 billion worth of fine art last year. That performance represented a more than 60 percent improvement over 2020, a roughly 25 percent increase over 2019, and the most lucrative year of fine-art auction sales on record.

The less inspiring news? It only edged the previous market peak in 2014 ($16.3 billion) by about $300 million. Even worse, after adjusting for inflation, the 2021 total actually underperforms the 2014 total by about $2.2 billion in today’s money.

A few weeks earlier, the annual report sponsored by Art Basel and UBS estimated that $65.1 billion worth of art and antiques changed hands across sectors. While those results also indicate a strong bounce-back from the estimated $50.3 billion in turnover in the report’s 2020 edition, they made 2021 only the third-richest of the past 12 years based on Dr. Clare McAndrew’s studies, trailing 2018 ($67.7 billion) and 2014 ($68.2 billion). In fact, last year’s total veered closest to 2011, when McAndrew and her collaborators estimated that annual sales hit $64.6 billion.

The two reports vary significantly in their analytical approaches. Close readers probably already clocked that the Intelligence Report strictly tracks auction sales. The Art Basel and UBS report, in contrast, aims to track sales of fine art and decorative art across the auction and dealer sectors. Most controversially, a significant chunk of data about the latter arrived via two anonymized surveys that each yielded less than 800 viable responses, 55 percent of which came from European dealers this time. Fifteen years into McAndrew’s use of limited survey results as a global indicator for a private market largely immune to fact-checking, most individual readers long ago decided to either criticize the annual dealer data as an exercise in spin and guesswork, accept it as flawed but still valuable, or blow right past the issue without noticing.

My point isn’t to debate which report’s methodology is superior; it’s to call out that major differences in approach returned basically the same verdict about the art market’s stagnant medium-term growth. Whether you rely on the Artnet Price database or a competitor, whether you look at the auction sector exclusively or try to add in the dealer sector, whether you restrict the lens to fine art or factor in decorative art too, the findings say that sales in our niche industry have not meaningfully increased in eight years.

So, why not? And what does it mean going forward?

The Microscope Hall at the wndr museum. Photo courtesy of the wndr museum.

THEORIES OF THE CASE

It goes without saying that the questions above are too big for one column to answer definitively. But to me, there are five possibilities worth considering.

1. A Pandemic Hangover Held Back What Would Have Been a Year of Major Growth.

Although most art buyers and sellers were vaccinated against COVID by last spring, the virus still nixed or hobbled multiple signal events for the trade. On the fair side, Frieze New York happened in May but was a downsized, exploratory enterprise; the return of Frieze Los Angeles had to wait until 2022; and onerous quarantine protocols for international travelers muted the tentpole fairs in Asia during the spring and fall. On the auction side, the Big Three houses’ spring sales in New York only went ahead by relying on a hybrid model; more broadly, the uncertainty may have led some collectors to wait to sell trophy works until the landscape stabilized.

Still, the Intelligence Report and the Art Basel/UBS report essentially agree that sellers would have needed to move another $2 billion to $3 billion worth of art just to match the market’s (inflation-adjusted) high from seven years earlier. They would have had to close deals worth a few billion dollars more to meaningfully surpass that apex. Even if every fair, auction, gallery opening, and pop-up event had taken place in ideal market conditions, would it have made a $3 billion to $5 billion difference in sales?

The Verdict: I don’t buy it. Especially since colossal pandemic-induced gains in net worth actually meant top buyers could (and likely did) spend more on art than they would have if COVID never happened.

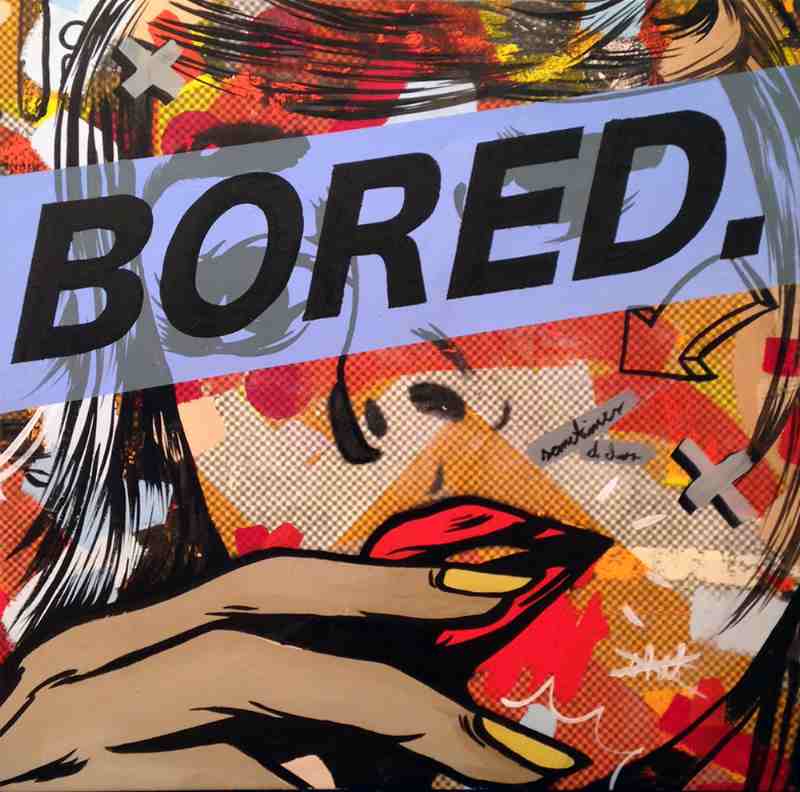

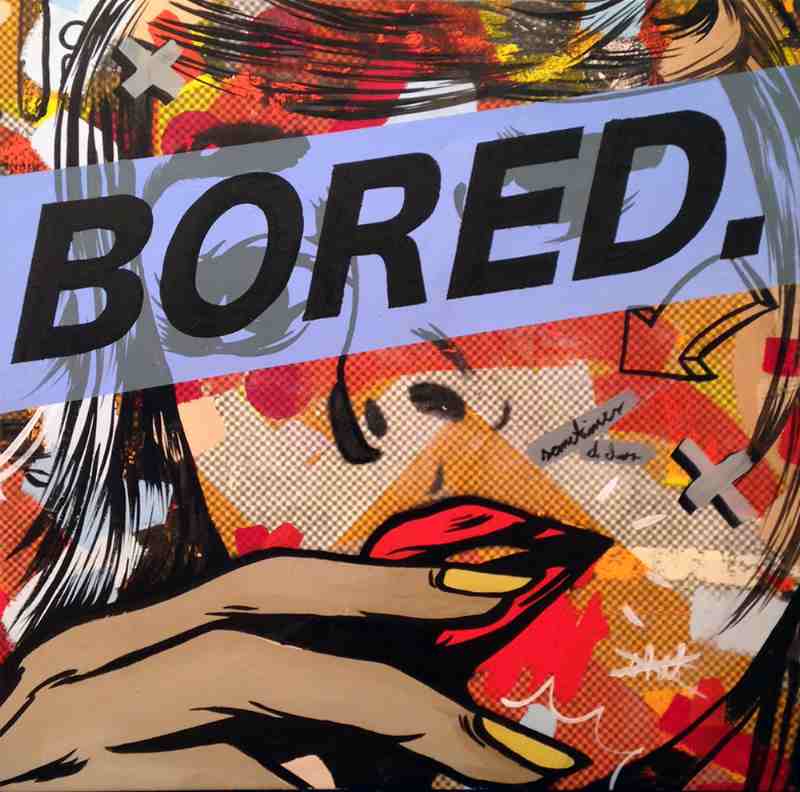

Daniel Monteavaro, Bored (2014). Courtesy of DTR Modern Galleries.

2. Art Sellers Don’t Actually Care About Growing the Market.

Call it snob-onomics. By this theory, the ample rhetoric about democratization and opening up art collecting has no more sincerity to it than the average political-campaign promise. It’s just a public-relations move papering over the reality that art sellers are content to keep selling to roughly the same cohort of high and ultra-high-net-worth individuals as they have for the past decade. The precise demographics making up the client pool might change somewhat, but the overall size won’t, because successful sellers have no real need for it to grow.

The Verdict: This reasoning is weak, too. No matter where each individual’s motivations fall on the spectrum between burnishing artists’ legacies and straight-up profiteering, most dealers and trade insiders are striving to sell as much art as possible to as many buyers as can pay the right prices (known flippers aside). Otherwise, top galleries and fairs would not be expanding to multiple locations around the globe, and top auction houses would not have jettisoned their centuries-long patrician histories to start hawking sneakers and NFTs almost as soon as a high-end market for both categories appeared.

In short, not every art seller is trying to conquer the world. But enough are thinking about it for me to neutralize the theory that they’re fine with maintaining the status quo.

3. Art Sellers Care About Growing the Market, But Their Methods Haven’t Paid Off (Yet).

This one is pretty self-explanatory, though it does support some variance in perspective.

The most pessimistic version holds that art sellers are trying to do the right thing, but need to reevaluate their strategies. For instance, embracing online sales was supposed to unlock a large, lucrative pool of new buyers, especially after the online-viewing-room boom of 2020. And yet it doesn’t seem to have, based on the art market’s inability to surpass its 2014 sales totals across reports. For that matter, neither has any other method. So, time to go back to the drawing board.

In the more forgiving version, art sellers’ efforts to expand the buyer base just need some tweaks and/or more time to take root. After all, you don’t transform a centuries-old market overnight. Whether we’re talking about online sales, digital marketing campaigns, the development of in-house publishing and/or podcasting divisions, a push into artist-branded merchandise, or any other strategy that would have seemed impossible or embarrassing in the 20th century, art sellers’ recent outreach efforts will be worth it in the longer run.

The Verdict: Here’s one adage that has proven true in too many situations: things change slower than you think, then faster than you could possibly imagine. Overall, then, this theory probably has some merit. I just don’t think it’s as influential as the remaining two.

The scrum at Art Basel 2019. Photo by Andrew Goldstein.

4. Art Sellers Care About Growing the Market, But the Buyer Base Is Already Near Its Upper Limit.

Economics plays an important role in this theory. Until wealth distribution meaningfully reverses the winners-take-all course it’s been on for decades in rich countries, or until a much larger pool of upper-middle class buyers somehow emerges in ascendant nations (or both), the buyer base for art can only expand incrementally.

But there’s a more subversive prospect in play here, too: that not nearly as many people will ever care about fine art as most art professionals want to believe. We already know that those of us devoting a meaningful chunk of our lives to galleries, museums, auction houses, biennials, et al. make up a self-selecting splinter group of the world population. We also have a natural tendency to assume that because we feel so passionately about this stuff, everyone else should, too—and if they don’t, it’s only because the rest of us haven’t reached them in the right way yet.

What if this thinking is just dead wrong? In other words, maybe the main reason for the trade’s decade-long inability to scale up isn’t that art pros have been using the wrong methods of outreach; maybe it’s because there simply aren’t that many more people interested in becoming paying customers in the first place.

The Verdict: To me, there’s more truth than trolling to this theory. But I’m also powerless to prove it.

Clothing featuring Basquiat’s imagery. Photo: Katya Kazakina.

5. The Art Market Is Growing, But Traditional Sales Data No Longer Captures It.

Love it, hate it, or begrudgingly accept it, popular definitions of “art” in 2022 are broader than ever, even within the hallowed halls of the art establishment.

The evidence is everywhere: The leadership of a mega-gallery launched a company largely dedicated to selling tickets to experiential installations. One of the most important painters of the last 50 years has become the posthumous kingpin of a merch empire. Thousands of visitors regularly pay to visit major art fairs as if they were museums. Some top artists are signing with Hollywood entertainment agencies to direct movies and TV shows. Public institutions are now selling NFTs of works in their collections. I could keep going…

Some of these endeavors are meant to create bridge transactions: smaller purchases that eventually lead to actual art sales later on. But most people paying to see, say, a teamLab exhibition will never even buy a limited-edition print, let alone a painting or sculpture from a dealer or an auction house. Does that mean their money and interest is worthless, though? And if we were able to factor in more of this ancillary spending, how much different might our perception of the market’s growth be in 2022?

The Verdict: It’s arguable that traditional acquisitions are all that should be counted when we try to quantify the size of the art market. Yet taking such an old-world view closes us off to more and more of what the art business is becoming in the 21st century. That fact doesn’t mean we should ignore that art sales have been stuck in place for close to a decade. It does, however, make it more important than ever to keep in mind what, exactly, we mean when we try to measure progress.

[The Artnet Intelligence Report / The Art Market]

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: what you see depends on where you decide to look.