Auctions

A 19th-Century William B. T. Trego Painting Was Long Thought Lost Until a Public Library Put It Up for Auction. It Fetched More Than $14,000

The painting sold for 190 percent of its high estimate.

The painting sold for 190 percent of its high estimate.

Sarah Cascone

At just 19, painter William B.T. Trego burst onto the U.S. art scene with a prize-winning work at the Michigan State Fair titled The Charge of Custer at Winchester—even though he was so paralyzed that he could barely hold a brush. That was in 1879.

Last month, that painting, which art historians had believed to be lost for generations, emerged unexpectedly at auction in Cincinnati at Hindman. The rediscovered canvas, expected to fetch just $3,000 to $5,000, sold to a private collection for $14,490 with buyer’s premium—an impressive 190 percent above the high estimate, with the price driven up by eight competing bidders.

It was the second-highest result ever achieved by the artist, according to the Artnet Price Database, falling short only of the $42,000 sale of Cavalry Charge of the Union Army at Christie’s New York in 2007.

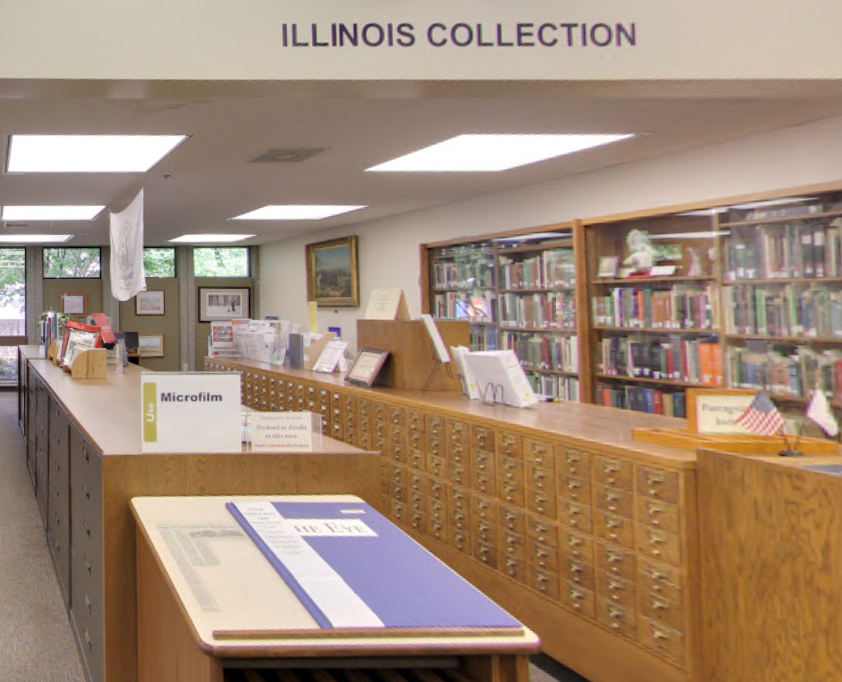

Where had the painting been all these years? Hiding in plain sight, hanging near the microfilm machines in the Illinois section of the Bloomington Public Library, about two-thirds of the way between Chicago and Springfield.

The Bloomington Public Library, Illinois. Photo courtesy of the Bloomington Public Library, Illinois.

“I was and still am stunned by the reappearance of the painting, as it had achieved a kind of legendary status among those of us who care about Trego’s work,” Joseph P. Eckhardt, the author of the artist’s catalogue raisonné, told Artnet News in an email.

The rediscovery was also a surprise for Hindman, which immediately started getting calls about the work when it published the lot listings for the March 30 auction.

“It’s always fascinating to find something that had been thought to be missing for so many years,” Ben Fisher, Hindman vice president and senior specialist of American furniture, folk and decorative arts, told Artnet News. “This is just a very powerful image—you have a really great rendering of Custer on horseback with his sword raised, charging into battle. It’s just phenomenal.”

The Charge of Custer at Winchester was one of about 40 pieces from the library’s 150-work art collection that the institution opted to sell to fund an expansion and renovation project. Appraisers had taken a look back in 2006, and found the signed Trego canvas to be the most valuable of the lot—but the library had no knowledge of its prior history and its import to the artist’s oeuvre.

The provenance for the painting has some gaps. Until the recent auction, the only record was an American diplomat named John C. White purchasing it for $1,000 in 1884. The only thing known about him is that he was the secretary to the American Legation in Brazil in 1879.

“John C. White is a bit of a ghost,” Fisher admitted. “But I think the odds of him being from Bloomington are pretty strong!”

William B.T. Trego’s The Charge of Custer at Winchester hanging in the Illinois Collection at the Bloomington Public Library, Illinois. Photo courtesy of the Bloomington Public Library, Illinois.

It was a man name Adlai Ewing—related in some way to Adlai Ewing Stevenson, vice president under Grover Cleveland, and his grandson Adlai Ewing Stevenson II, Democratic presidential nominee in 1952 and ’56—who gave the painting to Bloomington. It remains unclear when Ewing, who died in 1920, made the donation, or when or how he acquired it himself.

“I looked hard and I couldn’t find documentation—I even went through the minutes from all the library meetings,” Rhonda Massie, the library’s marketing manager, told Artnet News.

But despite the mystery, the library is thrilled to have played a role in this rediscovery—and with the above-estimate result of the sale.

“I thought it was pretty exciting!” Massie said.

The Charge of Custer was the first work the young artist had ever publicly exhibited, and it was hailed by the critics. The Cleveland Press called it “one of the best historical paintings of the kind that has ever been produced by an American artist.”

Its sale gave Trego the money he needed to enroll at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art, studying under Thomas Eakins for three years before later moving to Paris to take classes at the Académie Julian.

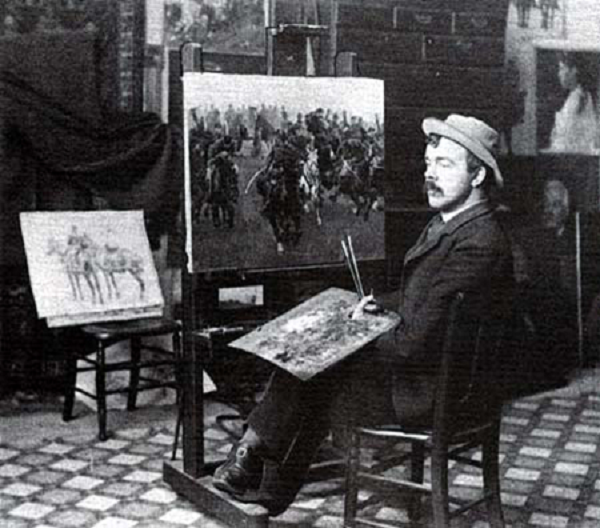

This artistic success was remarkable, given that Trego had become partially paralyzed in his hands and feet after a severe illness—likely polio—at the age of two. The son of artist Jonathan K. Trego, the younger Trego was fortunate that his father recognized and fostered his talent despite these physical infirmities, encouraging him to pursue making art.

“His output was not voluminous,” Eckhardt said, “partly because of his handicap, and partly because he insisted on working slowly and carefully in the old academic techniques his father taught him.”

Despite his early success, Trego fell on hard times in his later years, especially after the deaths of his parents.

“Sadly, the quality of Trego’s artistic work and imagination peaked at almost the exact time that his preferred genre—military history painting—lost favor with the public, and he found in the mid-1890s that sales and new commissions were increasingly hard to come by,” Eckhardt said. “Trego found himself alone in an empty house he couldn’t afford or maintain. Increasingly ill with post-polio syndrome, and on the verge of moving in with relatives, he ended his own life in June 1909.”

The artist William B. T. Trego in his studio in 1893. Public domain, U.S.

It was actually a public library that led Eckhardt to Trego. When he retired from Montgomery County Community College in Blue Bell, Pennsylvania, in 2007, Eckhardt donated all the art books from his office to his local library in North Wales, Pennsylvania. The librarian told Eckhardt that North Wales had been home to an important American artist, and shared some clippings about Trego’s life.

“I was blown away by the story of a severely disabled artist whose talent and force of personality had enabled him to make a successful career for himself in the late 19th century,” Eckhardt said.

He began researching Trego with the idea of writing an article. That project snowballed, and in 2011, Eckhardt curated “So Bravely and So Well – The Life and Art of William T. Trego,” the first comprehensive exhibition of the artist’s work, at the Michener Art Museum in Doylestown, Pennsylvania. The show was timed to the publication of the catalogue raisonné on the museum website, as well as a biography of the artist of the same name.

Part of the hope for the ambitious, multi-part project was that the catalogue raisonné could become a resource for tracking down the many Trego works whose whereabouts had been forgotten as the artist had fallen into obscurity in his later years and the century-plus following his death.

“In the past 12 years, several dozen have been found, including a wonderful self-portrait Trego painted while a student under the tutelage of Thomas Eakins,” Eckhardt said.

The artist’s catalogue raisonné details 179 paintings, drawings, sketches, sculptures, and photographs—only 17 of which have ever come up at auction, making the recent sale something of a rarity.

“The Charge of Custer is the biggest prize we’ve reeled in yet,” Eckhardt added. “There is no other painting in this artist’s oeuvre that could delight me more by showing up so unexpectedly.”