Art & Exhibitions

artnet Asks: Albert Oehlen and Wolfgang Voigt on the Intersection of Art and Techno

The long-time friends' collaboration includes a dead tree and a hard bass.

The long-time friends' collaboration includes a dead tree and a hard bass.

Henri Neuendorf

Albert Oehlen’s latest exhibition is all about juxtapositions. The show consists of a single work, Baum 3, which was created in collaboration with legendary German techno producer, Wolfgang Voigt, and is based on Oehlen’s ongoing tree series.

Driving to the Jablonka Gallery’s Böhm Chapel in Cologne’s industrial outskirts, the irony isn’t lost on artnet News that the quintessential bad boy of German art is showing his latest work in a former church. Approaching the chapel, a deep, pulsating beat becomes gradually palpable. Inside, the silhouette of a tree flickers on a large, free standing canvas featuring a pink square painted on its top-left corner. Walking around the semi-translucent canvas reveals a barren, unrooted tree clasped to a platform behind it. A stage light flashes in a rhythm matching Voigt’s pulsating bass drum to cast the tree’s silhouette.

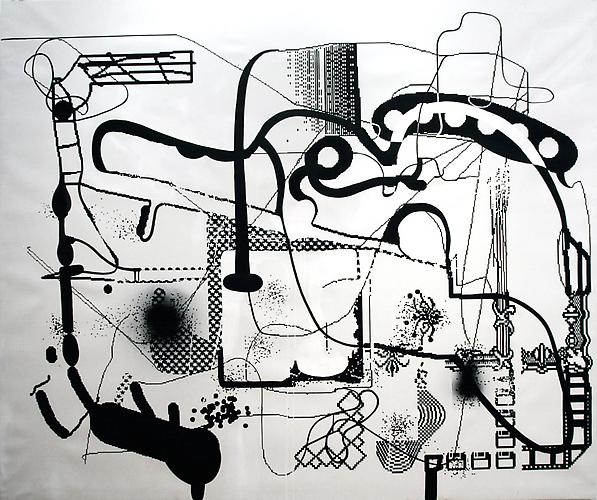

Installation view, Albert Oehlen and Wolfgang Voigt Baum 3 (2015)

Photo: Philip Niederlag, Courtesy Jablonka Galerie, Köln

In the early days of his career in the 1980s, the German painter Oehlen was one of the most provocative artists in Germany. He developed an unorthodox painting style and participated in bizarre projects in a deliberate ploy to offend Germany’s art establishment.

Often mentioned in the same breath as his friend and compatriot Martin Kippenberger, who also showed with then Cologne-based dealer Max Hetzler, the two moved to Spain in the late ’80s to further develop their practice. It’s during this time that Oehlen started to adopt a more abstract approach to painting, which he has by-and-large maintained to this day.

Installation view, Albert Oehlen and Wolfgang Voigt Baum 3 (2015)

Photo: Philip Niederlag, Courtesy Jablonka Galerie, Köln

Oehlen has always pushed the boundaries of painting to its limits, experimenting with different styles and materials from rudimentary finger painting and oil colors, to computer graphics, digital printing, and spray painting.

Wolfgang Voigt revolutionized music much in the same way. He was a pioneer of the techno genre and co-founded the influential techno label Kompakt with fellow producers Michael Mayer and Jürgen Paape. He’s considered one of the founders and leading producers of minimal techno, and is known for his tireless productivity; since the early 1990s, he has released an astonishing 160 albums.

In 1993, Voigt opened the popular record store Delirium in Cologne from which Kompakt was born. It was here that he first met Oehlen, who would occasionally stop by to buy records. artnet News spoke to the two old-time friends and first-time collaborators before the opening of their joint exhibition.

Albert Oehlen Self-Portrait with Soiled Underpants and Blue Mauritius (1984)

Photo: Art in America

[To Oehlen] In the ’80s you had a reputation of an enfant terrible. Were your paintings provocative because of you, or were you provocative because the of the paintings?

Oehlen: No idea, I don’t remember how it was. I know that I have this reputation, but I’m not sure why. There was a picture called Self Portrait With Soiled Underpants, which is my best known picture and I’m fairly certain it was only provocative because of the title. Salvador Dalí made a similar painting, and it upset [surrealist artist and writer] André Breton but nobody after that. I don’t know where the provocation lies. Although I think the most aggressive aspect of my early work was actually ignoring aspects of painting that the people considered imperative: that one should have a feeling for color, for composition; certain things that make up a bourgeois understanding of what art should be, and which I deliberately neglected, but in this case really in order to provoke. This actually worked, although it wasn’t interpreted as a deliberate provocation, instead people got upset and thought it was stupid. [laughs]

In the late ’80s you adopted a more abstract style—what led you to this change?

I would say I painted abstractly to take a step, and there are various reasons for this which I cannot reveal, or don’t have to. But one reason is that I thought, oh, I’m doing the same thing as art history. This aspect which was part of the change was something that I found interesting.

Albert Oehlen Untitled (1993)

Photo: Art in America

How has your relationship to painting changed over the years?

My relationship, if it’s changed? I never really changed my attitude. But I would brazenly say that I changed my painting!

You’ve always worked by yourself and never used assistants. Why? That isn’t really common these days.

The reason is that I like to be alone. And it’s hard to find a person whom I could trust that much. Look, it’s not just that he or she could watch me paint in the studio, they’d be able to look inside my brain, to see me think! I don’t grant that to just anybody. I did however have assistants a couple of times where it worked and where I specifically experimented with this scenario; the purpose was not to produce faster or more, rather to test this constellation. I worked with Merlin Carpenter who’s a well-known artist now and with Daniel Richter for a short time, for two weeks, and later with some of my students.

Albert Oehlen Untitled (1992)

Photo: Skarstedt Gallery

You’re one of the first painters to use modern technology in painting, for example in your computer paintings in the ’90s. Do you think artists should integrate technology into their work?

I’m actually not competent with technology at all. The use of computers had a certain ironic aspect because the end result of the experiment—even after the first painting—was that I painted the whole thing anyway. It was a game, an illusion. From my perspective there’s nothing to be gained. The only thing that I do with the computer these days is use photoshop to evaluate a work in progress; to see if its really worth painting the entire left side of the canvas pink, or if I’ll very quickly regret it.

How did this collaboration between the two of you come about?

Wolfgang Voigt: Even before the current installation, we’ve been in touch for a while, Albert has long been interested in my music, and in techno. Over the last year we started to talk about art and were interested in each other’s way of working and thinking about the intersection of music and art. What’s possible? What’s not possible? We discussed musical stuff, which led to some funky remix projects that I released on my label. The current project is based on a series that Albert has been working on for a long time—now in its third edition—and because it’s always had a musical, acoustic aspect he invited me to this confrontational collaboration, an interweaving of the sonic and visual senses.

Wolfgang Voigt at Kompakt Records, Cologne in 2012.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Have you always been following each other’s work throughout the years?

Voigt: I’ve always had an eye on the visual arts. As a child of Cologne in the ’70s and ’80s I was of course exposed to the artistic movement of the time. In my opinion, Albert was always one of the most extraordinary artists whose work always fascinated me. It was exciting because I recognized an intuitive visual language in the pieces that didn’t require extensive discourse or a broad understanding of his work. As it turned out he was also listening to my music and interestingly was able to make very insightful comments about it which I hadn’t gotten before.

[To Oehlen] I read that you didn’t even go to the clubs, but were familiar with Voigt’s music, how did you come across his work?

Oehlen: I enjoy listening to music while I work, and I especially like his stuff. That doesn’t mean that I listen to it all day [laughs] but when I listen to techno then his stuff is my favorite. He does a lot of projects, and I knew, even without knowing him, just by looking at the titles and names he used, that this is somebody who thinks artistically, and this made me want to get to know him.

Installation view, Kunsthalle Zürich, Zurich, 2015

Photo: Stephan Rohner courtesy of the artist and Kunsthalle Zürich

Regarding the installation—you’ve used the motif of the tree repeatedly since the 1980s, what is it about this motif that makes you want to keep revisiting it?

Oehlen: The thought of what would happen if one interpreted the crazy, chaotic and disorganized formation of the branches as an analogy of the artist in front of the empty canvas not knowing where his brushstrokes will lead. No detail is fixed, no aspect is fixed. It’s reminiscent of what the helpless artist does in front of the canvas. And then of course with this project, the contrast; the prophet of the straight line [looks towards Voigt, laughing], and me, the prophet of great confusion…

Voigt: It’s the friction between the concrete and the abstract, the audible and the visual let loose against each other. The tree, symbolic of natural naivety is juxtaposed against the aggressive bass drum, it makes one think the tree has to be taken out of harm’s way. This friction in this sacred space creates a symbiosis.

Oehlen: It’s an ascension and a sacrifice at the same time, it has this double aspect.

If you could own any artwork in art history, what would it be, and why?

Oehlen: I have no idea, if one can look at an artwork one can have it, that’s my understanding of art.

Voigt: I would like to answer similarly, it changes all the time, I would think it fatal to choose only one artwork.

Oehlen: Actually, today I would chose the Philip Guston picture with the nails—hammer and nails, I’m not sure which one it is, but there’s a Guston picture with a hammer and nails.

Voigt: I’d like a different one every three years!