Analysis

Kenny Schachter Gives the Dirty Details Behind the Big New York Auctions

Warhols and Twomblys and Wools, oh my!

Warhols and Twomblys and Wools, oh my!

Kenny Schachter

Jim Shaw, Dream Sculpture (2006),

Image: Courtesy of Phillips

I covered the fall New York art auctions—focusing more than usual on the art itself for a change—for another art publication, and the editors there knew full well in advance that my writing voice verges on…hysterical, littered with random gossip and innuendo that for the most part is entirely true no matter how cartoonish it may appear at first blush. (The last thing anyone wants to hear from me is my opinion about the actual art: only who’s showing, buying and selling. Period.) I’m no Cindy Adams, who signed off her NY Post gossip columns: “Only in New York, kids, only in New York.” But the art world is a not a place unto itself, kids, it’s a veritable planet.

There was a sculpture by Jim Shaw (b. 1952) subject of a retrospective at New York’s New Museum, at Phillips day sale entitled Dream Sculpture from 2006 made of hay, wood and metal estimated at $40,000-$60,000, which failed to sell, one of 208 works by the artist to appear at auction. I’m not saying it was a factor in the lack of performance of the work, but a slightly conceited—bordering on arrogant—(very) young collector I know kind of tampered with it and another work after an alcohol-soaked lunch before the sale.

During the preview, the guy took some hay lifted from Shaw’s Dream and inserted it into a collage on canvas by Korakrit Arunanondchai (b. 1986). Plainly visible central to the composition of piece, which hadn’t been removed when I saw the artwork a day later, was a chunk of hay stuffed into the burnt denims affixed to the face of Arunanondchai’s canvas. I can imagine the hay being individually wrapped if the work is ever subsequently lent to an exhibition, forever preserved in its wrongfulness. Morally, I should have removed it, but I was too embarrassed.

Oh yeah, the protagonist-collector, who has on occasion referred to himself as a genius (always a reassuring sign), also called himself Stingel-damus, after Nostradamus (1503-1566), the self-proclaimed seer of prophecies, due to how many Rudolf Stingel’s he squirreled away before the recent price surge. Clever genius.

Speaking of Stingel, an uptown gallery that may have an exquisite exhibition by the artist (up through January), albeit the single most unstable conservationally, comprised of brittle Celotex insulation board, foam and silicone, but I won’t say who. The whippersnapper, who went straight to the gallery after spending a night and early morning at a rave (or whatever kids do when they’re out all night), was lamenting the fact that I’ve given too much ink (or the digital equivalent) to one Larry G and should mention him more. Well, here you are, dude.

How about a twisted tale from a trusted source, make of it what you will—there I’ve disclaimed. There is a high profile, in-the-auction-rooms young Turkish spec-u-lector, Kemal Cingillioglu, with more than a lot of money at his disposal, hailing from a family that is heavily into energy production, distribution, banking, insurance, leasing, factoring, and real estate. You get the idea.

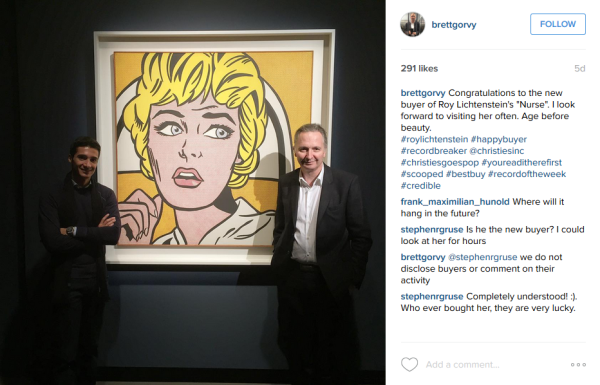

He is spearheading, with his dad, a major push into art and seemingly under the spell of Brett Gorvy, Chairman and International Head of Post-War and Contemporary Art at Christie’s. Charming as he is, Brett Insta-famously posted an image of the $95 million Lichtenstein (the unpublished estimate was $80 million) flanked by himself and Cingillioglu on Instagram, with the caption that he looks forward to seeing the Lichtenstein often in the days to come, intimating that Cingillioglu was the buyer and creating an Insta-pickle in the (mostly) discreet art world. We need human delete buttons to prevent more tripping over ourselves.

Cingillioglu was the seller of the Andy Warhol Marilyn, guaranteed for $44 million that breathtakingly managed to make $8 million evaporate in less than a New York minute when it came up well short, selling for $36 million, the third time the painting exchanged hands (or storage facilities, I should say) in two years.

More beguiling was the gossip swirling before the sales that Gorvy coaxed Cingillioglu into buying a mega-wattage Cy Twombly “blackboard” painting at monster-millions and before he could say, “What’s my guarantee?,” Sotheby’s beat them to the punch and secured another for auction before Christie’s could sign off. Unquestionably the market could not support more than one $70 million scrawl per sale cycle and they had to bite the bullet and hang on for the next roll of the dice when the market may drift further into iffy land. Or it may not, but it’s doubtful the “collector” was amused to lose that race.

To try and cover their ass, another source revealed that Christie’s hit up the obvious bidders of the Twombly at Sotheby’s—the air is thin above $10 million, the players are widely known by all (except me)—to simultaneously shop the Cingillioglu painting, and that could account for the fact some market watchers found the $70 million surprising: on the low side (!), as others were dissuaded from fighting over one when another was right behind it in the pipeline. You get an idea of how deals are churned and murkily rolled sale to sale, sometimes substituting art for currency itself: canvas coinage.

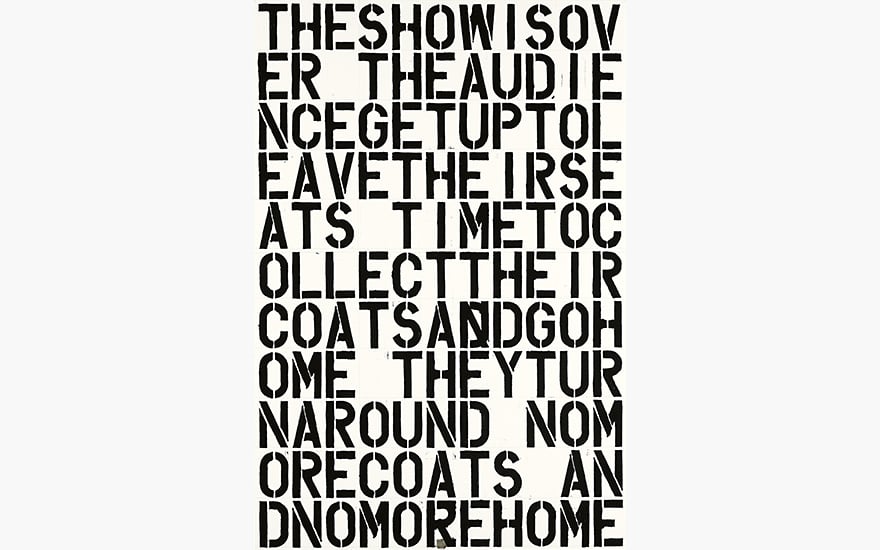

Christopher Wool, Untitled: The Show Is Over.

Image: Courtesy of Christie’s

In the Christie’s “curated” Artist’s Muse auction manufactured around the sale of the $170 million Amedeo Modigliani (1884-1920), as good a reason as any to conjure an auction with no connections to the intended subject matter, which inexplicably included a Warhol gun (thought the artist was particularly disinclined towards revolvers) and a Christopher Wool (b. 1955) text work. The Wool on paper, entitled The Show is Over from 1990, contained the text: THE SHOW IS OVER THE AUDIENCE GET UP TO LEAVE THEIR SEATS TIME TO GET THEIR COATS AND GO HOME THEY TURN AROUND NO MORE COATS AND NO MORE HOME. Well, estimated to sell for a steep $5,000,000-$7,000,000, the Wool actually made it home—but the home from where it came, not to a new owner. And the story of how it went down is a doozy.

A maverick private dealer with a reputation for good art and short temper was selling the above-mentioned Wool on behalf of a prominent A+ old school collector before the sale and was informed from a prominent gallerist in LA that he had a certain client, a television talk show host, who I will only say isn’t a man, isn’t Rosie O’Donnell, and is a known contemporary art collector. The deal was done for $3.8 million but unbeknownst to the celebrity, who is a real-life client of the gallery, she was a straw dog for a consortium of dealers, including another in New York who also works with all the same participants in the shenanigan. The investor group (do we need these in our profession?) turned down $5.4 million and a guarantee at $5 million, twice: once from the house and another from a third party. Greed knows no bounds: it was bought in, unsold. And having lost face with the prominent collector, the maverick dealer—pumped with dealer rage (who once threatened to break my knees, another story, kids)—told the LA gallery owner he’d stab him if he showed up for the New York auctions. Needless to say, he wasn’t seen.

Wool’s CATS IN BAG BAGS IN RIVER, enamel on aluminum also from 1990, sold for $17 million at Christie’s second evening sale of contemporary art (a single evening sale used to do the trick). Now the cat is out of the bag: From my research, I located the painting on the Rubell Family Collection (RFC, sounds like KFC) Museum web site. True there is often more than one iteration of many of the catchiest Wool text works, but I’m not sure Cats is one of them. Granted, it’s not a flip when you’ve owned it since it was ten dollars a million years ago, but it’s not a keep either. Or a museum move if that’s what you hold yourself out to be. And from what I understand, it’s not an isolated example of the family employing Christie’s removal service. I guess $17 million is an awful lot of hotel rooms in South Beach or Washington, D.C.

In my earlier auction report, I mentioned the records of Math Bass (b. 1981) at $81,250 (est. $25,000 to $35,000) at Phillips, Petra Cortright (b. 1986) at $40,000 (est $25,000-$35,000) at Sotheby’s day sale and Aaron Garber-Maikovska (b. 1978) at $97,500 (est. $15,000 to $20,000) at Sotheby’s. I am the most paranoid, idealistically cynical person you will meet but it never even occurred to me that those results might still have been manipulated to such heights after the collapse of the zombie formalist flip-flop market. Maybe, but I just don’t buy it as when the bill comes, you have to pay, whether its your first or 12th.

I’ve been away from the New York for well over 11 years in London and must say I’m missing the gravitational pull of the city and stupefying mother’s lode of art institutions, galleries, artists and collectors. Speaking of which, I’m actually considering a move back—horror of horrors for those who finally grew used to my absence, though I’m still mightily ubiquitous on a computer near you. A realization I made after launching my apartment hunt in the quest to return next year (more or less) is that Richard Prince and Christopher Wool, like it or not, are the official house artists of the city, hanging in fully five of the nine venues I visited.