Market

Richard Diebenkorn’s Daughter Challenges Ann Freedman’s Story at Knoedler Forgery Trial

Gretchen Diebenkorn Grant said the works she saw "had no soul."

Gretchen Diebenkorn Grant said the works she saw "had no soul."

Eileen Kinsella

The second day of the high-profile Knoedler forgery case, which is being held in the Southern District Court in Lower Manhattan, started with opening arguments by the defense for Knoedler & Co. and its former president, art dealer Ann Freedman, and ended with testimony from prestigious art world figures who appeared on behalf of plaintiffs Domenico and Eleanor De Sole.

The De Soles are suing for roughly $25 million for a painting they spent more than $8 million on, believing it was the work of Abstract Expressionist master Mark Rothko.

The witnesses on Tuesday afternoon included esteemed art historian and MoMA chief curator emeritus John Elderfield, as well as Gretchen Diebenkorn Grant, the daughter of iconic California painter Richard Diebenkorn.

During their respective testimonies, they described several instances in the the mid-1990s, during Freedman’s tenure as president, when they viewed purported Diebenkorn works at the gallery that they considered “dubious” or “not right.”

The works in question came from Long Island dealer Glafira Rosales, who brought the works to Knoedler under the premise that they had been handled by the Vijande Gallery in Spain. They were among a group of about 40 works that were eventually confirmed as forgeries painted by an amateur Chinese painter in Woodhaven, Queens.

A courtroom sketch of Gretchen Diebenkorn Grant on the witness stand at the Knoedler gallery trial.

Photo: Elizabeth Williams, courtesy ILLUSTRATED COURTROOM.

Under cross examination, Freedman’s attorney, Luke Nikas, attempted to demonstrate that “from the very beginning,” Freedman had disclosed that Rosales was the source of the “Vijande” gallery works by producing a Knoedler letter that said Elderfield had deemed the works attributable to Diebenkorn.

When Elderfield took the stand, he talked about his extensive knowledge of Diebenkorn’s famous “Ocean Park” series, describing numerous visits to the artist’s Santa Monica studio during which he looked at artworks and slides and observed not only original works but also the process by which they were created.

He described a 1994 visit to Knoedler with the artist’s widow, Phyllis Diebenkorn, during which he observed two paintings executed in the style of the “Ocean Park” series in Freedman’s office.

“My reaction was that they were very dubious,” said Elderfield on the witness stand. “I said to Phyllis, ‘Can we talk about these?’ I felt they were not done by the same artist whose work I’d seen very extensively. …These seemed flat and bland…the line on top didn’t read like a windowpane,” as genuine Ocean Park series works do. Years later, upon learning that the works had been sold, Elderfield described his reaction as “surprised and dismayed.”

When Gretchen Diebenkorn took the stand, she discussed numerous visits to Knoedler during the 1990s, during which she saw the same works shown to Elderfield. Asked about these same works, she responded, “They had no soul. They didn’t breathe.” She said there were times when “the work just didn’t look right.” She also said that she had noted their lack of provenance and pointed out as much to Freedman.

On one occasion of viewing such work and telling Freedman that she had concerns, Diebenkorn said Freedman didn’t react as one might expect. “She didn’t say ‘Oh dear,'” said Diebenkorn. “Subsequently the work was sold.”

“John Elderfield and Gretchen Diebenkorn Grant clearly said, as we promised in the opening, that the first works from Rosales were not right, and that’s what they told Freedman at the time,” Emily Reisbaum, an attorney for the De Soles, told artnet News via email. “We were surprised that defendants also brought out that Knoedler and Freedman handled another set of fake Diebenkorns, from Dino Rossi.”

The name Dino Rossi, who apparently was a source of other questionable works unrelated to the ones Rosales proffered, appeared in a 1995 letter from the gallery to Phyllis Diebenkorn.

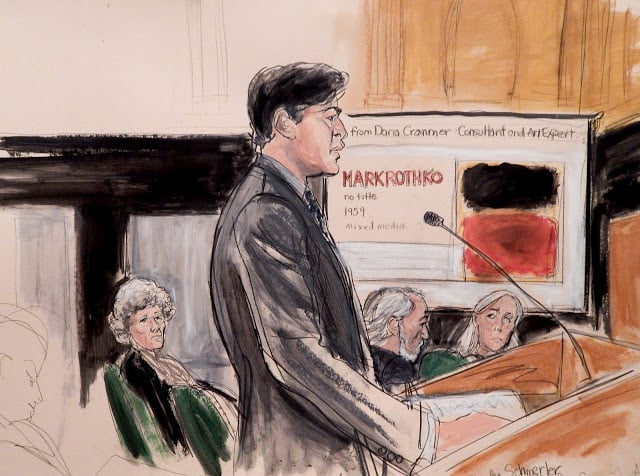

A courtroom sketch of defense lawyer Charles Schmermer at the Knoedler gallery trial.

Photo: Elizabeth Williams, courtesy ILLUSTRATED COURTROOM.

Asked about the letters dated from 1995 that he presented to the witnesses, Nikas told artnet News via email, “The documents demonstrate that Ann Freedman disclosed to the Diebenkorn family from the very beginning that Glafira Rosales was the source of the Vijande Gallery works. And Ms. Freedman distinctly remembers the family approving the works.”

In an April 2012 story in Vanity Fair, prior to the confirmed existence of a forger and when Freedman was still claiming that the Rosales works were authentic, writer Michael Shnayerson looked into the story of the Vijande Gallery in Spain, where Rosales had purportedly gotten these Diebenkorns.

According to the report, Freedman turned to Rosales in 2006 for help in shoring up the provenance of one of these paintings that had been acquired by the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, in Kansas City:

Rosales interviewed one Cesareo Fontenla, a Spaniard from Madrid, who answered a series of questions from Rosales about how he came to acquire the paintings from Vijande before they went to Knoedler.

Fontenla declared he had a restaurant called Taverna César, located on Fleming Street, near La Castellana Plaza, in Madrid, from the late 1970s until 1985. It was an artists’ hangout: everyone from Francis Bacon to Andy Warhol had come through its doors. Many were brought to the restaurant by gallery owner Fernando Vijande. In 1981 and 1982, Fontenla said, he acquired the Diebenkorn works from Vijande, “some as part of a trade for a work by Dalí, and some in payment for Mr. Vijande’s account at the restaurant.”

The gallery did exist, until Fernando Vijande’s death, in 1986. But Rodrigo Vijande, the late dealer’s son, finds Fontenla’s story incredible. “I would say I know at least 90 percent of the artists who went through the gallery,” he says when reached in Spain. Diebenkorn wasn’t one of them. Nor has Rodrigo ever heard of the Taverna César. “Both galleries that my father owned in Madrid were right where he lived, in front of his house, on Núñez de Balboa, in the center of Madrid,” Rodrigo notes. “Fleming Street is about two or three miles away.” Not, perhaps, an implausible distance except, says his son, that the gallery owner didn’t drive. That was why he lived some 50 yards from his galleries.

It’s unclear to what extent the Vijande gallery provenance will be further explored at trial given that all of the works that have been connected to Rosales and Knoedler have been proven to be forgeries.

The trial continues today.