Galleries

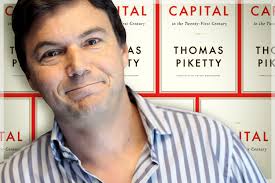

Lessons from Thomas Piketty About Rampant Art World Inequality

What does the French economist's bestseller portend for artists, dealers, curators?

What does the French economist's bestseller portend for artists, dealers, curators?

Benjamin Genocchio

When I hear consternation about Thomas Piketty’s surprise new bestseller Capital in the Twenty-First Century, it’s hard for me to believe that it’s somehow “breaking news” to anyone in New York’s art world that capital is concentrated in the hands of the few and is becoming even more concentrated in those hands. Don’t get me wrong here, for this isn’t an angry rant about class warfare. If you are interested above all in making, accumulating, and spending money, by definition you gravitate (in many but of course not all cases, it seems to me) either towards Wall Street or any industry that feeds off the tech boom or maybe even Big Pharma. Long story short: You don’t work in finance if you don’t like or understand or hope to accumulate money.

If being around creative, aesthetically minded, often visually gifted people is important to you, then the art world is the place to be—even if financially you are punished for it. Most artists and art world workers are at peace with the choice they have made: Lifestyle over income. For most of us worker bees in the art world, a degree of control over work and personal time is more important than, strictly speaking, earning money.

Most artists and art world workers are happy and willing to interact with the oligarchs and financial types because those people are the patrons who fund the exhibitions that help sell artworks. People in the art world understand the reality: Fundamentally it is a small wealthy elite that makes the wheels turn, supporting art museums and buying art, creating jobs so a whole lot of people like us get to do what we love. As has been for all time, it seems to me. No problem there.

The income inequality, whether growing or not, and which we benefit indirectly from, isn’t so troubling as what I will call the “opportunity inequality” that has come with increasing stratification of wealth. Opportunity inequality means bigger and more voracious galleries, individual mega-artists and museums getting all of the money, and fewer chances to succeed for the young seat-of-the-pants galleries that have traditionally been incubators for new artists. At least that’s how it seems to me it is shaking out here in New York. Which is why perhaps new opportunities are coming from different parts of the country—or different countries. Or different models, like these communal artist groups that pop up in various biennales.

Also, since the government has cut back on funding to art and artists, philanthropists have increasingly had to pick up the slack and are demanding more for their museum dollar—wings and rooms named after them, and increasingly requesting museum shows drawing upon their own collections. You could probably make an argument that what has changed is that it is now too expensive in New York (real estate, operational costs) for anyone but Big Business art world enterprises to survive. You either get with the money program, in short, or get pushed out of the industry. Little wonder art schools teach artists how to survive in the system. There is no more outside.

As actual real estate for art in New York disappears, online real estate for art expands, to some degree. I notice the online appetite for street art has expanded, also for prints and photos. So it is not all negative, with the art world evolving online to attract a different kind of collector. Innovation is all around us, sure, but the concentration of opportunity and power in the hands of a few dealers, collectors, and artists is a problem. It has, overall, been tremendously limiting, even stifling of creativity.

Fifteen years ago, when I first came to New York, small nonprofit organizations such as Artists Space, Art in General, apexart, Exit Art, and the Drawing Center were fundamental presences in the New York art world. They received state and city grants—foundation support too. They were integral to what made the art scene turn round each day and each year. Today you barely hear about them as they struggle for attention, even survival, in a vastly changed media and fundraising climate for artists and nonprofits.

Structural change in the art world also challenges traditional roles and responsibilities for institutions: The expansion of Chelsea into a big box megagallery sales center over the past two decades has created a bustling and very competitive marketplace that is most responsive to global art that can be rapidly bought and sold. We all benefit from this power center for art sales, but has it become like the Dow Jones of the art world, where stocks are bought and sold? You are, as an artist, a part of a “tradeable asset class,” or you aren’t.

All this is to say that it’s difficult to ignore that the current age of oligarchy in which we are living, as Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century articulates, widens the fissures between the lucky few who have an opportunity to live creatively and those who don’t. That’s what I mean by opportunity inequality. I see it grow every day.