Analysis

LVMH Shelled Out $47 Million to Keep a Caillebotte Masterpiece in France. So Why Are People Complaining?

LVMH is entitled to a major tax break after buying the painting.

LVMH is entitled to a major tax break after buying the painting.

Eileen Kinsella

Luxury goods conglomerate LVMH, which is owned by the French billionaire art collector Bernard Arnault, made headlines around the world last week when it was revealed that the company had shelled out €43 million (nearly $47 million) to acquire Gustave Caillebotte’s famous Impressionist painting The Boating Party for the Musée d’Orsay.

In early 2020, the painting was deemed a national treasure and thus denied an export license. France then had a period of 30 months to come up with the necessary funds to buy the work and keep it in the country. With an annual acquisitions budget of just €3 million, the likelihood that the state-owned Musee d’Orsay could come up with the funds was slim to say the least.

So voilà! LVMH came to the rescue. The painting was unveiled, to much fanfare, at a museum ceremony last week attended by Musée d’Orsay president Christophe Leribault, minister of culture Rima Abdul Malak, and Jean-Paul Claverie, advisor to Bernard Arnault.

(L to R) Christophe Leribault, president of the Musee d’Orsay, minister of culture Rima Abdul Malak, and Jean-Paul Claverie, advisor to Bernard Arnault, president and director general of LVMH.

“Thanks to the exclusive patronage of LVMH, I am delighted that this masterpiece will enrich the heritage of the nation and can be presented in several cities in France,” said Malak.

“LVMH thus affirms, once again, its commitment to the preservation and promotion of the national artistic and cultural heritage,” said Claverie.

Amid the celebration, some were quick to point out that under French patronage laws, LVMH is entitled to a massive tax break—as much as 90 percent of the purchase price (so long as that amount falls within the limit of 50 percent of the tax due). Does that strip away some of the benevolent luster of such a massive donation? It depends on who you ask.

It's not a "€43m donation from LVMH" since the operation allows the conglomerate a 90% tax cut on the 43m: in fact it's almost only the French tax payers who pay for it @garethharr @TheArtNewspaper https://t.co/S7Zf4EJM8K

— Magali Lesauvage (@MagLesauvage) January 31, 2023

Journalist Magali Lesauvage tweeted: “It’s not a ‘€43m donation from LVMH’ since the operation allows the conglomerate a 90% tax cut on the 43m: in fact it’s almost only the French tax payers who pay for it.”

“This law on corporate sponsorship in France is widely criticized,” said Paris attorney Beatrice Cohen. “It creates a dichotomy between the essence of sponsorship, i.e. the donation, and the fiscal compensation that is granted to the sponsor, which some consider to be disproportionate, believing that it is more a matter of defiscalization and publicity for the sponsor than a real involvement in cultural sponsorship; private individuals do not benefit from such ‘fiscal advantages.'”

Call it a “friendly tension,” between tax collecting entities and French cultural organizations, said Paris attorney Anne-Sophie Nardon, who specializes in art law.

“The program is very popular, but it’s not popular with the treasury department,” she said, noting that the tax break means a loss of revenue for them. (We reached out to France’s ministry of finance, but a representative directed us to contact the ministry of culture.)

“It seems fair,” Nardon said of the inter-agency tension, “that even if the price is high, the company that is offering/donating money for the purchase of the painting should benefit from the tax deduction. This has been a huge help for the Louvre, for instance, which has been able to acquire several national treasures because of this patronage law.”

Overall, she calls it a “win-win” strategy.

“This law established in French public life the idea that philanthropy was not only useful but necessary and that it was up to it to promote the general interest, alongside of course the public authorities and among others the state,” said Jean-Jacques Aillagon, the former culture minister who spearheaded the now two-decade-old law, and who is an advisor to Francois Pinault. “The results of this law are regularly established by the government but also, for cultural patronage, by private organizations such as Admical. This assessment is positive.”

Aillagon was not involved with any of the recent negotiations for the Caillebotte, but told Artnet News in an email that he was “delighted” to see the painting join the Musée d’Orsay’s collection.

Asked how he responds to critics of the patronage structure, Aillagon said: “There is a misunderstanding here. The 90 percent tax reduction is not a gift to the company that buys a national treasure, but the authorization given to it by the state to allocate part of the tax it owes to an action that the state has declared to be in the general interest, on condition that it adds a sort of voluntary tax, in this case the 10 percent of the price of the work not covered by the reduction.”

“I would like to add that this system allows our museums and libraries to benefit indirectly from an increase in their acquisition budgets, which are often very modest,” he said. “In France, their ability to acquire works of art is also supported by the dation system, which makes it possible to pay inheritance tax by handing over works of art. This is essentially how the collections of the Picasso Museum were built up, first by the estate of Pablo Picasso himself, and then by his heirs.”

Claverie, who advised Arnault on the transaction, also sees the structure as a win-win. He noted that this acquisition is the highest price paid to date to keep a “national treasure” in the country.

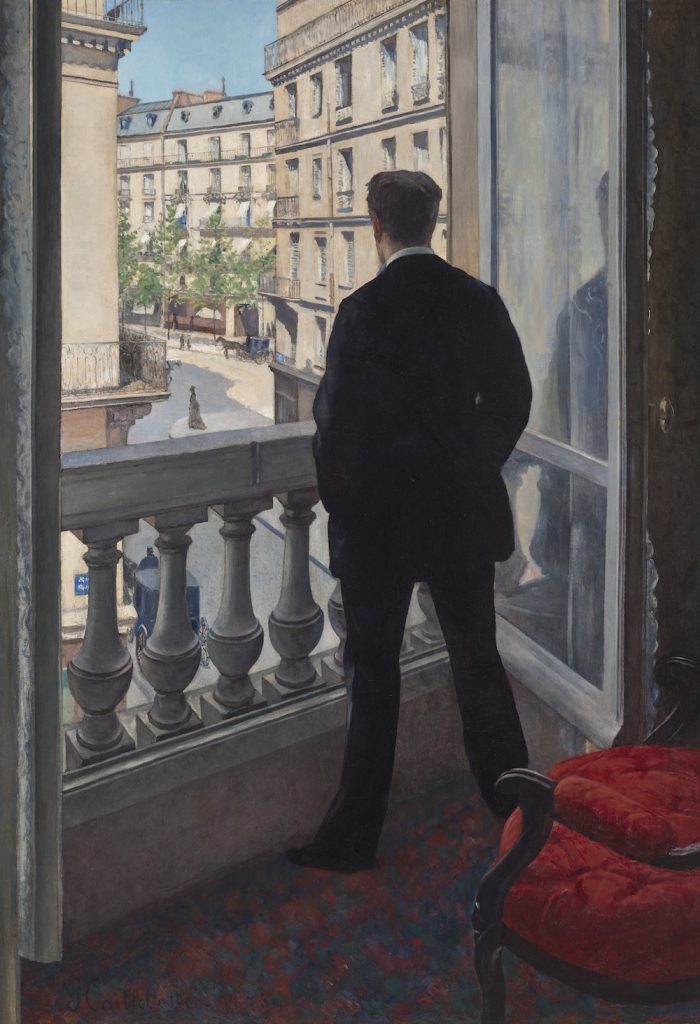

Gustave Caillebotte, Jeune homme àsa fenêtre (1876). Image courtesy Christie’s.

It also marks the second-highest price ever publicly recorded for a Caillebotte painting. The record of $53 million was set in November 2021 when Christie’s sold Jeune homme à sa fenêtre (1876), part of the collection of late oil magnate Edwin Cox, to the Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

Claverie noted that Boating Party is one of the last masterpieces in private hands in France, noting that the image is famous and has appeared in dozens of catalogues and art history books, but had rarely been seen in person because it was in private hands. “Now they can come to the Musée d’Orsay and see it in real life. It’s an enrichment but also a discovery and a gift to the people.”

Claverie noted that the work is part of LVMH’s broad philanthropic efforts, which extend to music, medicine, and a variety of other programs. “We were very, very enthusiastic about this acquisition and gift to the national collection.”