Galleries

Major Unidentified Lucio Fontana Painting Authenticated After Decade of Research

Coline Milliard

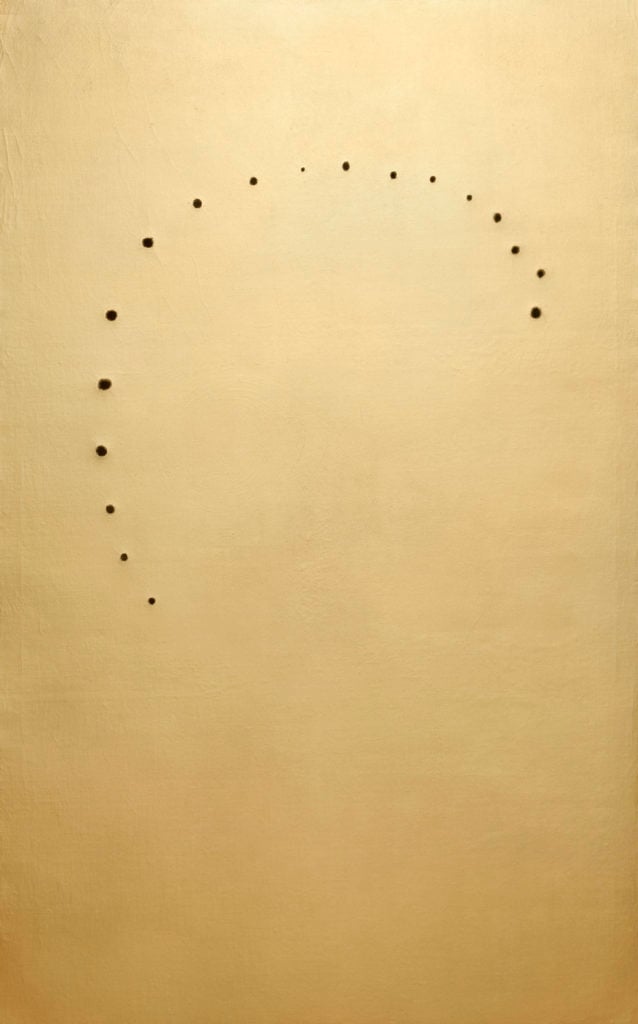

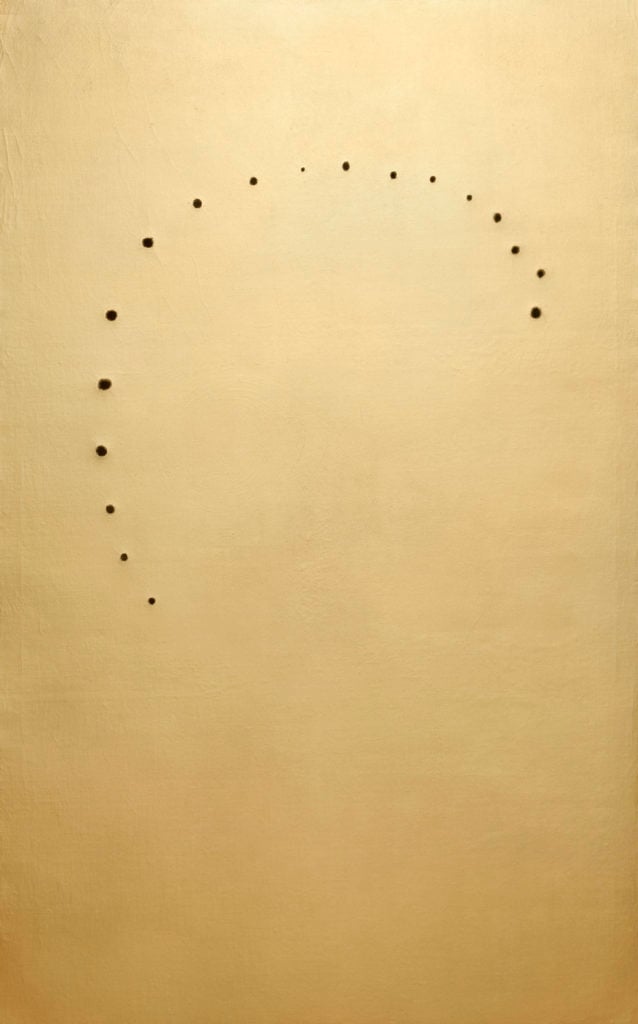

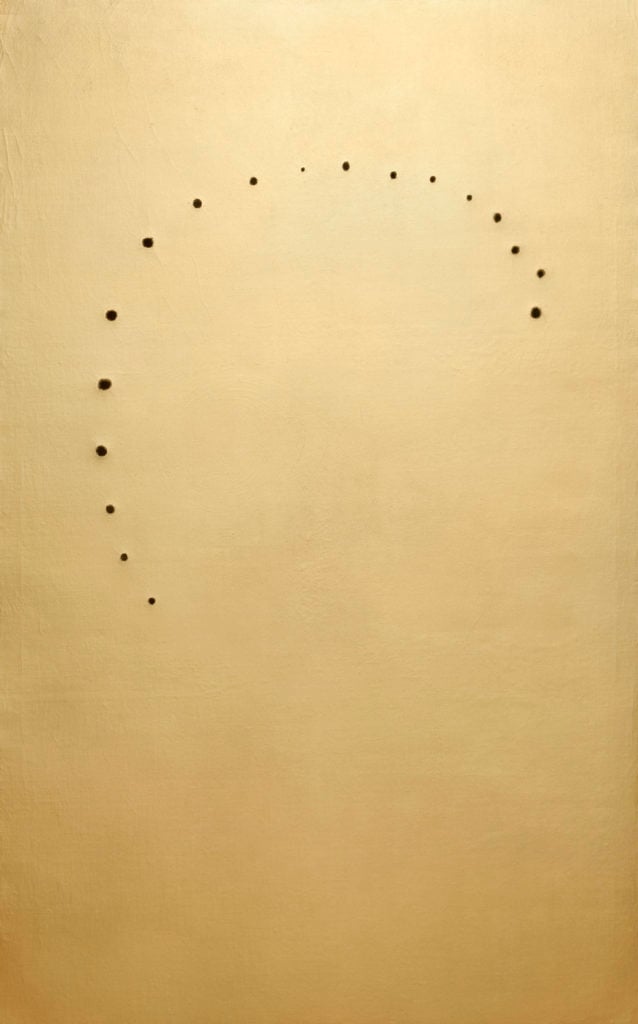

Lucio Fontana and Le Jour, 1962

Courtesy Filip Tas

In the early noughties, founder of Tornabuoni Art Paris Michele Casamonti was invited by a collector to take a look at his Lucio Fontana. What followed is an extraordinary research project that led to the authentification of a major piece, until now so little known that it had slipped through the net of the Italian artist’s enormous catalogue raisonné.

Talking to artnet News, Casamonti recalls the moment he first cast an eye over the piece. “When I arrived in the house, I found myself facing a gigantic painting, relatively spectacular and I say ‘relatively’ because it was almost suspicious to see such a large Fontana, what’s more, a golden one, and one which, crucially, was unidentified.”

The owner (a European collector who has chosen to remain anonymous) informed the dealer that his father purchased the piece, but he didn’t know when. “I realized there was a page [of the Fontana story] waiting to be written,” says Casamonti. Entitled Le Jour and dated from 1962, the piece sheds light on an obscure episode of Fontana’s life: his trip to Knokke, Belgium, at the invitation of the artist Jef Verheyen, who was more than thirty years his junior. The young artist asked Fontana to intervene on a monochrome painting, and he obliged on November 12, 1962, during a performance at the house of Belgian collector Louis Bogaerts. The painting was titled Le Jour.

Best known for his “slashed paintings,” Fontana is one of Italy’s great modern artists. He was born in Argentina in 1899, but spent much of his life in Milan, where he become a champion of Spazialismo, or Spatialism, which aimed to expand the understanding of space. Fontana’s quasi cult status means that research on his work abounds, and Casamonti was puzzled by the lack of information on Le Jour. It took him more than a decade to piece the puzzle together.

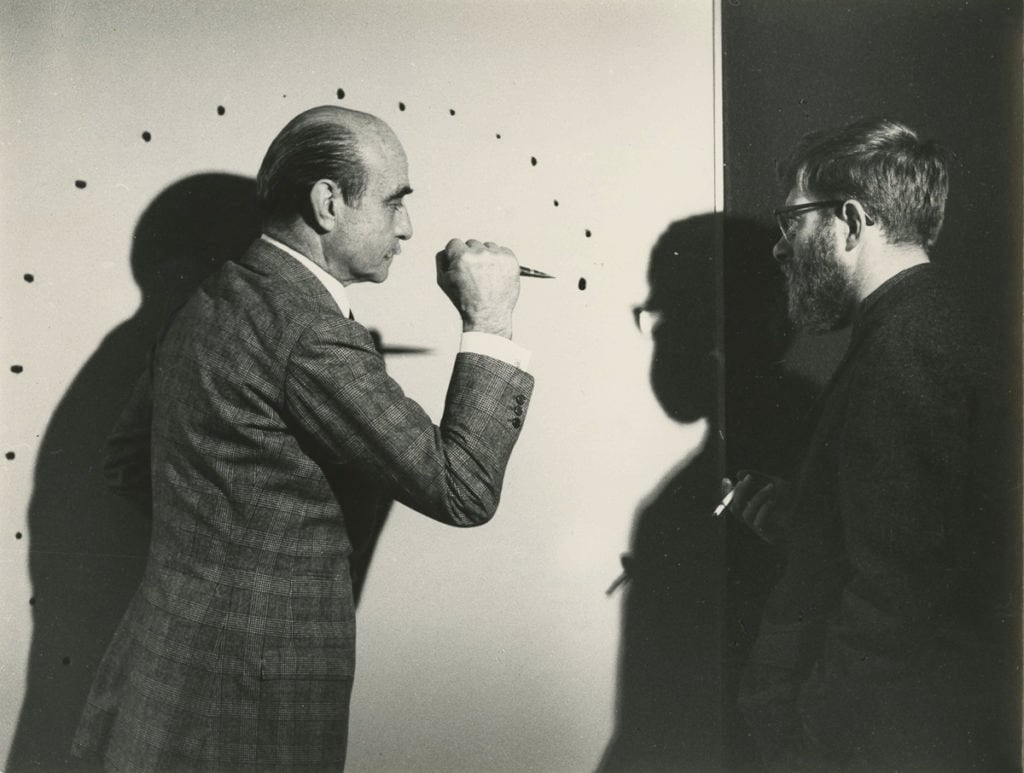

During his investigation Casamonti stumbled across a video of the artist executing the Le Jour and filmed at Bogaerts’ house. Only a handful of people knew about the film, originally broadcasted on the Belgian television BRT/ VRT on December 3, 1962. It cropped up in France in 2007, when the art critic Valérie da Costa screened it at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris.

Lucio Fontana, Le Jour, 1962Courtesy Tornabuoni Art

“It’s very interesting because it shows the physical position of Fontana in front of the canvas,” comments Casamonti. “It also shows how Fontana studies his gestures before realizing them. Preparation is almost more important than the execution, which is instinctive, total, and immediate.” The only filmic record of the artist at work, this video turned out to be the missing link.

“I insist,” says Casamonti, “we haven’t found an unknown Fontana in someone’s attic. Each element was known separately.” Fontana’s collaboration with Verheyen was already well documented. Léonore Verheyen, the daughter of Jef Verheyen, knew of the painting, which her father had exhibited as part of a triptych alongside two of his other works in the 1970s. But she had no idea of Le Jour’s current whereabouts. Spurred by the video, the dealer strung the clues together one by one. The Fondazione Lucio Fontana then conducted an extensive analysis of the painting, its materials, signatures, and compared the spaces between the holes in the video and in the actual painting before eventually giving its stamp of approval.

This is a real coup for Tornabuoni Art. Next spring, the gallery will be presenting the piece alongside the video in an exhibition focusing on the artist’s production between the year of his first concetti spaziale, 1950, and his death in 1968. The video will also be included in the major Fontana retrospective opening at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris on April 25, an exhibition for which Tornabuoni Art is one of the main lenders.

To describe the Fontana market as buoyant would be an understatement. According to data available on artnet Analytics, the 2013 return on a 2003 investment is 609%. While Casamonti remembers seeing his father, the founder of Tornabuoni Art, sell a Fontana for the equivalent of €7,000. Now, the auction record is for the 1963 Concetto Spaziale, La Fine de Dio, which fetched US$20,885,000 at Christie’s New York last November. Although the dealer declined to give any indication of price for Le Jour, which will be negotiated privately, one can safely assume that it will reach in the seven figures.

The Italian dealer is confident the buoyancy is here to stay. “This isn’t a fad,” he says, pointing out that although works are sold regularly at auction, they are rarely bought in. “Fontana is an artist who has his place in art history. He is, at the same time, pricey and not expensive. It’s true that some of his pictures are commanding really high prices. But the work isn’t expensive when compared with other great masters of the 20th century. I think the progression will continue.”