Auctions

12 Crucial Takeaways From Last Week’s $1.9 Billion New York Auction Cycle

From the biggest flop to the best buy, here are our parting observations from last week's auction marathon.

From the biggest flop to the best buy, here are our parting observations from last week's auction marathon.

Artnet News

A staggering $1.9 billion worth of art was bought and sold at auction in New York last week. Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips stuffed 10 sales of Impressionist, Modern, and contemporary art into five very busy days. The combined haul across all three houses was $1.9 billion, up $300 million from the equivalent sales in May 2017, which made $1.6 billion.

What should market-watchers take away from the onslaught? Here are some parting observations.

A bidder at a Christie’s postwar and contemporary art sale in New York City. Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images.

After the so-called marathon auction “gigaweek,” Christie’s came out on top with a combined total of $959.6 million for evening and day sales, while Sotheby’s came in second with a total of $858.6 million, and Phillips, a distant third with $155.6 million. Though the ranking order was the same last May—Christie’s followed by Sotheby’s and then Phillips—all three auction houses posted sharp overall gains, with Christie’s up 15 percent (from $833.9 million), Sotheby’s up 35 percent (from $635 million), and Phillips up 21 percent (from $128.9 million). Notably, these figures all represent gross totals and don’t factor in any financing deals, third-party guarantees, or other arrangements that auction houses often use to secure high-profile material and that sometimes dip into their profit margins. (We also didn’t include Christie’s Rockefeller Collection sales, which took place earlier this month, to keep it a fair fight. You can read our recap of that extravaganza here.)

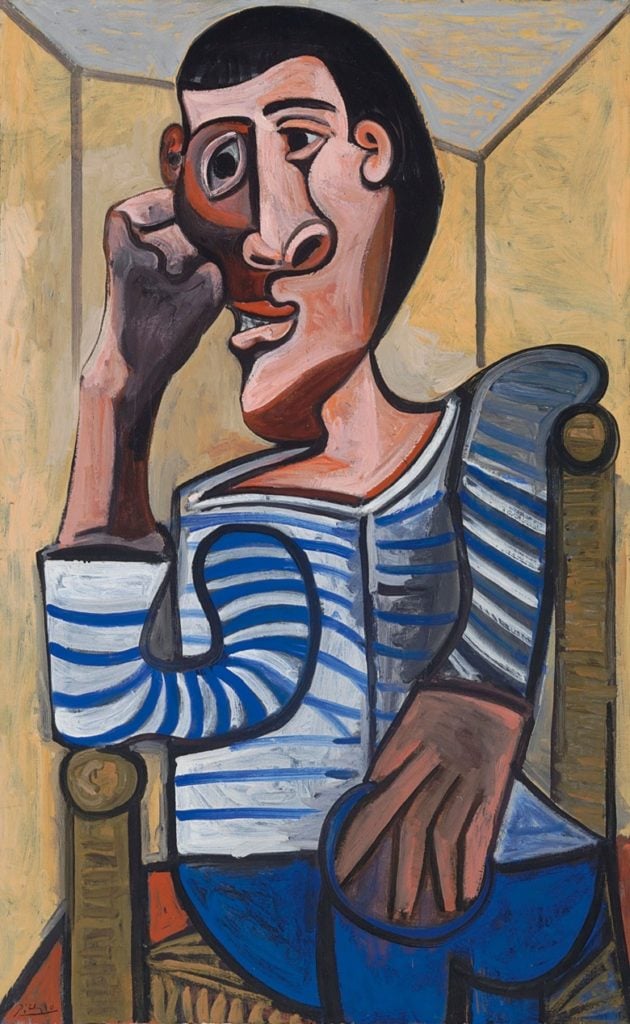

Pablo Picasso, Le Marin (1943). © 2018 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Image courtesy of Christie’s.

It’s difficult to find an auction situation more awkward than when bidding for a premier lot fails to meet expectations, but one of the few events that qualifies is the late withdrawal of a work due to damage. We were reminded of this last Friday, when Christie’s was forced to pull Picasso’s Le Marin (1943)—estimated, and guaranteed, in the region of $70 million—from its Impressionist and Modern art evening sale due to an accident “during the final stages of preparation.” (Word is an errant pole fell and punctured the canvas.) Adding insult to injury (or perhaps injury to injury): the artist’s 1964 painting Femme au chat assise dans un fauteuil was withdrawn soon after “by mutual agreement” with seller Steve Wynn, who had also consigned Le Marin. Together, the two works sapped an estimated $105 million from an otherwise successful sale.

Sotheby’s Impressionist and Modern art evening sale on May 14, 2018. Photo: Eileen Kinsella.

Although multiple expected star lots met or exceeded their high estimates this week, these results tended to come courtesy of only a handful of bids. Other pieces anticipated to soar into the stratosphere never reached cruising altitude. But activity was much more frenetic for works lower on the value scale: either modest pieces by all-time greats, such as Claude Monet and Mark Rothko, or significant works by artists still new to blue chip status, such as Kerry James Marshall and Mark Bradford. Overall, this trend suggests that one of the market’s current drivers is a focused pursuit of undervalued assets with long-term staying power, not price-blind trophy-hunting or the pump-and-dump strategy that has created and demolished so many young reputations in earlier market cycles. The main question now is: Will the same mindset still be dominant by November?

Left: Gerhard Richter, Abstraktes Bild (1991). Photo courtesy of Sotheby’s. Right: Richter’s Abstraktes Bild (811-2) (1994). Photo courtesy of Phillips.

This prize goes to the two most similar artworks with the widest variance in results. This season, both Sotheby’s and Phillips offered comparably sized, early 1990s Abstraktes Bilds as the cover lots for their respective contemporary evening sales. But while Sotheby’s 1991 Richter, estimated at $15 million to $20 million, sold for $16.6 million with buyer’s premium, its counterpart at Phillips—just 20 inches longer and completed three years later—passed at $10 million against a $12 million to $18 million valuation. The fork in the road proves once again that the only guarantees in the auction market are the ones made in writing (which the Sotheby’s consignor, unlike the Phillips one, received).

Alex Rotter, not texting. (Photo by Ilya S. Savenok/Getty Images for Christie’s)

In what is surely an auction first, Christie’s chairman of postwar and contemporary art Alex Rotter accepted a bid via text during the house’s evening sale on Thursday night. Amid the competition for Francois-Xavier Lalanne’s Surreal sculpture The Mayersdorff Bar (1927–2008), which ultimately sold for $4.6 million with premium, Christie’s auctioneer Jussi Pylkkanen asked Rotter, who was half turned away from the action and hunched over his phone, “Alex, are you texting or are you bidding?” The answer, as it turns out, was both. The bid came in via text at $3.3 million, to which Pylkkanen replied: “That’s a first.” One small step for iPhones, one large step for auction house specialist-kind.

Protestors from the Berkshires gathered outside of Sotheby’s auction house. Photo: Caroline Goldstein.

Several high-profile museum deaccessions moved ahead last week despite vocal opposition—and even a protest outside Sotheby’s against the particularly contentious Berkshire Museum sell-off. It’s difficult to tell if the hubbub had any effect on the outcome. So far, Berkshire works have sold in the neighborhood of their estimates, generating a total of $3 million of a stated $50 million goal, with a number of works still to be sold. The advocacy group Save the Art–Save the Museum plans to protest outside Sotheby’s again on Wednesday morning, when more works, including a multimillion-dollar Norman Rockwell painting, are set to hit the block. Meanwhile, Philadelphia’s La Salle University sold five works at Christie’s Impressionist and Modern sale for a total of $2 million, well above the combined $1.4 million high estimate. The university plans to dedicate the proceeds to educational programs, a decision that has angered many former staff members and museum supporters. Finally, the Baltimore Museum realized nearly $8 million (without premium) in sales for five works at Sotheby’s: a Warhol, a Franz Kline, a Jules Olitski and two Kenneth Nolands. The funds will be used to build up its collection of work by women and artists of color.

Mark Bradford, Speak, Birdman (2018). Image courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

It was one of the few works on the auction block this week that bore the stamp “executed in 2018.” Not everything offered by this darling of the contemporary market went gangbusters this week, but this particular painting, donated by the Los Angeles-based artist to help raise funds for the new Studio Museum in Harlem building, was like a meteor. The first of five works offered for the initiative, bids came so fast and furious that auctioneer Oliver Barker had trouble keeping up. Estimated at $2 million to $3 million, he opened bidding at $1.6 million and after a volley of bids both in the room and from the phones, it was quickly hammered down for $5.8 million, or $6.8 million with premium. Not only did the work double its high estimate, it is now the third highest price for the artist at auction. All that, and the paint is barely dry!

Constantin Brancusi, La jeune fille sophistiquée (Portrait de Nancy Cunard) (Conceived in 1928 and cast in 1932). Courtesy Christie’s Images Ltd.

The American collectors Elizabeth and Frederick Stafford bought Constantin Brancusi’s small polished bronze portrait of the eccentric Anglo-American heiress Nancy Cunard directly from the artist’s studio for just $5,000 while vacationing in Paris in 1955. Brancusi typically cast very small editions, and today the majority of his works are in the collections of major museums. (This one was on view at the Met for some time.) La Jeune Fille Sophistiquée was owned by the Stafford family for a stunning 63 years, and was consigned to Christie’s by the couple’s children. Their patience paid off. The work sold last Thursday for a stunning $71 million—a new auction record for the artist.

Robert Motherwell, At Five in the Afternoon (1971). Photo courtesy of Phillips.

Any artwork that sells for $12.7 million (and sets an auction record for the artist) isn’t exactly cheap. But hear us out: Given its quality, scale, provenance, and backstory, Motherwell’s At Five in the Afternoon qualifies as a bona-fide bargain for its new owner. A well-executed example of the artist’s famous “Elegy” series, the painting is in fact a copy of a smaller version of the same composition that Motherwell lost to ex-wife Helen Frankenthaler in the couple’s divorce settlement. Motherwell was so upset to lose the little artwork he loved so much that he painted a new version for himself—only much, much bigger.

The work is an homage to Spanish poet Federico García Lorca, who was thought to have been killed by right-wing extremists in 1936. (The painting is named after Lorca’s poem Lament for Ignacio Sánchez Mejías.) The work eventually found its way onto the wall of renowned Chicago collector Holly Hunt, who bought it from Motherwell’s gallery in 1981. Last Thursday’s sale at Phillips marked the first time it has appeared at auction. But don’t be surprised if you see it again—and it makes makes, much, much more.

David Hockney’s Pacific Coast Highway and Santa Monica (1990). Image courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Rarity can sometimes have a counterintuitive effect on a blue-chip artist’s market. For someone like David Hockney, top-notch works don’t trade on the open market as often as fans might think. (Why? For one, people tend to hold on to the best examples from sought-after series. Furthermore, some collectors prefer to sell through the artist’s primary market dealers and know they can get a price far above the public auction record for particularly rare works if they sell privately.) As a result, Hockney’s auction high coming into this season was a relatively modest $11.6 million. But that changed twice in a single night last week at Sotheby’s. First, a Hockney work on paper fetched $11.7 million and then, just 10 lots later, a major 1990 painting, Pacific Coast Highway and Santa Monica, soared to $28.5 million. Keep in mind, however, that neither example represents Hockney’s most famous swimming pool or double portrait series. If one of those ever makes it to auction now, hold onto your hats.

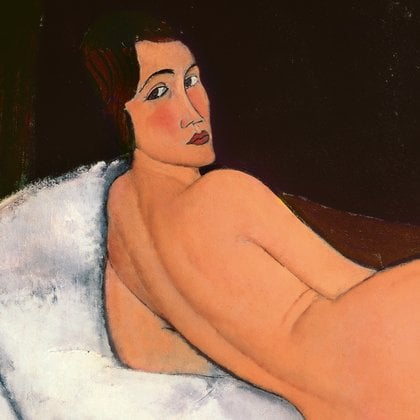

Detail of Amedeo Modigliani, Nu couché (sur le côté gauche) (1917). Courtesy Sotheby’s and Tate Modern.

As much as it is completely ludicrous to call a $157 million final result a disappointment, the pre-sale hype for Amedeo Modigliani’s Nu couché (sur le côté gauche) (1917) was so high that by the time the actual auction arrived, the extremely thin, lackluster bidding was not only surprising, but extremely anticlimactic. Auctioneer Helena Newman opened bidding at $125 million and talked it up (including some so-called “chandelier,” or imaginary, bids) to $139 million, where it was finally hammered down to a Sotheby’s specialist on the phone with a client, who sources say was the third-party guarantor.

Though the hammer price was far short of the expected $150 million, at these nosebleed levels, hefty premiums go a long way. The final price marks the highest ever achieved by Sotheby’s and the fourth highest ever recorded at auction.

The mechanics of today’s auction market, in which much of the action is determined in advance, contributed to the counterintuitively underwhelming feeling. “I think Sotheby’s did a remarkable job securing such an extremely high third-party bid for the seller,” said David Norman, a private dealer and former Sotheby’s executive. “While I think evidence often bears out that non-guaranteed lots with reasonable published estimate outperform guaranteed lots, this was a case where I think they found maybe the one (and only?) person who would commit to that price (assumed $150 million) and they may not have gotten to that price in an open competition.”

This season, the Modgiliani is the only new member of the so-called “$100 million club.” Only in today’s upside-down market could that be called an anticlimax—but here we are.

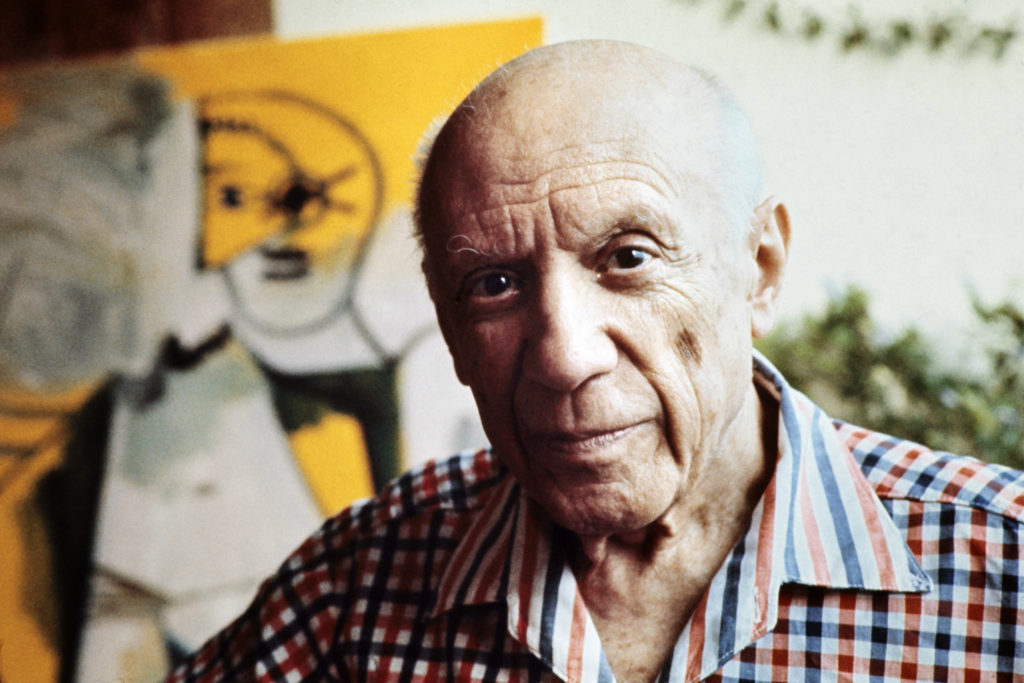

Pablo Picasso in Mougins, France in 1971. Photo: Ralph Gatti/AFP/Getty Images.

Although Modigliani generated the highest overall dollar value thanks to the sale of Nu couché, it seems disingenuous to hand him the title based on a single lot and the tepid bidding it inspired. Instead, the “best-selling” description applies more comfortably to Picasso, whose 29 sold lots brought a combined $116.7 million (including fees) into the three major houses last week. The Spanish master also posted an impressive sell-through rate of 78 percent (excluding lots withdrawn pre-sale). Most powerful, Picasso works generated 14.5 percent of all sales value in Christie’s and Sotheby’s Impressionist and Modern auctions this cycle, according to the artnet Price Database. (He was absent from Phillips’s 20th century and contemporary art sales this time out.) The results once again suggest that Picasso is to some degree playing the role of Atlas for the entire category, carrying the world on his back.