Galleries

The New Empire Builders: How Pace and Other Art Dealers Are Reinventing What a Gallery Space Should Do

Dealers are spending tens of millions on performance spaces and private viewing rooms, while smaller galleries close up shop.

Dealers are spending tens of millions on performance spaces and private viewing rooms, while smaller galleries close up shop.

Brook Mason

When Pace unveils its new eight-story gallery on 540 West 25th Street this week, the building will stand as a symbol of the lengths art dealers must now go to stay on top in the increasingly competitive elite art market.

The scale—and the costs—are staggering. Inside Pace’s 74,500-square-foot volcanic stone-clad building, which happens to be larger than the Met Breuer, are novel exhibition spaces and private viewing rooms; 2,200 square feet dedicated to showcasing new media work, performance, and public programming; a 10,000-volume research library open by appointment; and the kind of open storage that is becoming increasingly popular among new contemporary art museums. There is also a garden for sculpture on the roof, which can support art that weighs as much as 360 tons (not to mention a food truck for visitors).

This transformation does not come cheap. The building cost an estimated $80 million, according to reports, plus an additional $18.2 million to build out the interior. Oddly enough, Pace does not own even the building designed by New York-based firm Bonetti/Kozerski, but rather is leasing it from the developer Weinberg Properties.

Rendering of Pace Gallery’s new HQ at 540 West 25th Street, New York. Image: Bonetti /Kozerski Architecture.

In essence, the new, multi-faceted Pace building recasts the very notion of an art gallery and represents an increasingly pronounced shift in Chelsea away from smaller, modest showrooms and toward flashy, starchitect-designed bonanzas. Notably, the cost of Pace’s project is on the same level as the New Museum’s $89 million capital campaign.

But while the construction cost and the amenities are akin to those for any major museum, “the decided difference is that unlike museums, dealers are totally profit driven,” says Mark Walhimer, a partner at the consultancy Museum Planning, LLC.

It might seem counterintuitive that Pace and other major galleries are doubling down on brick-and-mortar at a time when retail is in crisis. There are now more than 20 empty storefronts on Madison Avenue. But the idea is that by transforming galleries into spaces for experiences and injecting dance, film, and music—a growing trend in the retail sector—galleries can become hubs of activity yet again.

For Pace, this concept has already proven lucrative. The mega-gallery may have roped in as much as $10 million in ticket sales alone from their teamLab exhibitions in Palo Alto, London and Beijing, which drew more than half a million people and charged $20 each for admission.

teamLab’s Universe of Water Particles on a Rock where People Gather, 2018. Image courtesy of Pace Gallery.

Incorporating dedicated space for performances and screenings is also a gamble that may help the gallery lure new multimedia artists, such as Nick Cave and William Kentridge, to join its roster.

But Pace has competition in the realm of high-gloss buildings. In all, at least eight Chelsea dealers—including Marlborough Gallery, Hollis Taggart, and others—are ramping up in scale and plunking down considerable sums for new quarters. Hauser & Wirth is adding 542 West 22nd Street, a new 7,400-square-foot building designed by Annabelle Selldorf that will include private viewing rooms.

David Zwirner is also in the process of building a five-story, $50 million flagship at 540 West 21st Street, due to open in 2021. It will be the first commercial gallery designed by the Pritzker Prize-winning architect Renzo Piano, who lent his talented hand to the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.

And Larry Gagosian, whose empire spans 178,000 square feet globally, with five spaces in New York alone, is also ramping up his Chelsea enterprise. He is now renting the former quarters of Mary Boone and Pace adjacent to his 26,000-square-foot gallery on West 24th Street. He paid $5.75 million to buy his Chelsea gallery in 1999, according to realtor Susan B. Anthony.

The largest galleries are not the only ones shelling out millions of dollars to remain competitive in the space race. Lehmann Maupin acquired three floors of a building in Chelsea—a total of 7,800 square feet—for $27 million, according to Ran Korolik, partner of the real estate firm the Victor Group, which developed the building. The new space opened last year.

The goal for these galleries appears to be to maximize the space available not only to artists, but also to collectors. Paul Kasmin’s latest space on 28th Street includes three private viewing rooms totaling 3,400 square feet, while a mere 460 square feet is set aside for public exhibitions and offices. Viewing rooms “allow us to spend uninterrupted time with collectors and curators in order to discuss a single work in detail,” says Nick Olney, a Kasmin director.

The facade of Kasmin Gallery, Photo Courtesy Kasmin Gallery, © Roland Halbe.

That expansion connects to Kasmin’s 509 West 27th Street flagship, which is studded with a stunning 28 skylights and cost a reported $8 million, according to one source.

Are such gargantuan expansions sustainable, considering their hefty price tags? It seems likely, as West Chelsea continues its transformation into a high-gloss destination for billionaires and millionaires (as well as tourists) thanks to the massive $20 billion Hudson Yards development.

But as mega-galleries erect giant art fortresses in Chelsea, smaller dealers are cashing out and fleeing to less competitive and expensive shores. Longtime Chelsea dealer Julie Saul has picked up stakes and is now dealing privately. Andrea Rosen and Luhring Augustine recently sold their joint 24th Street space to a developer for $28 million (though the latter gallery is currently leasing back the space and staging shows there). And Murray Guy, Mike Weiss, Kansas, and even the 25-year stalwart CRG Gallery have shuttered their doors in recent years, while Cheim & Read vacated its Chelsea storefront for a small gallery uptown.

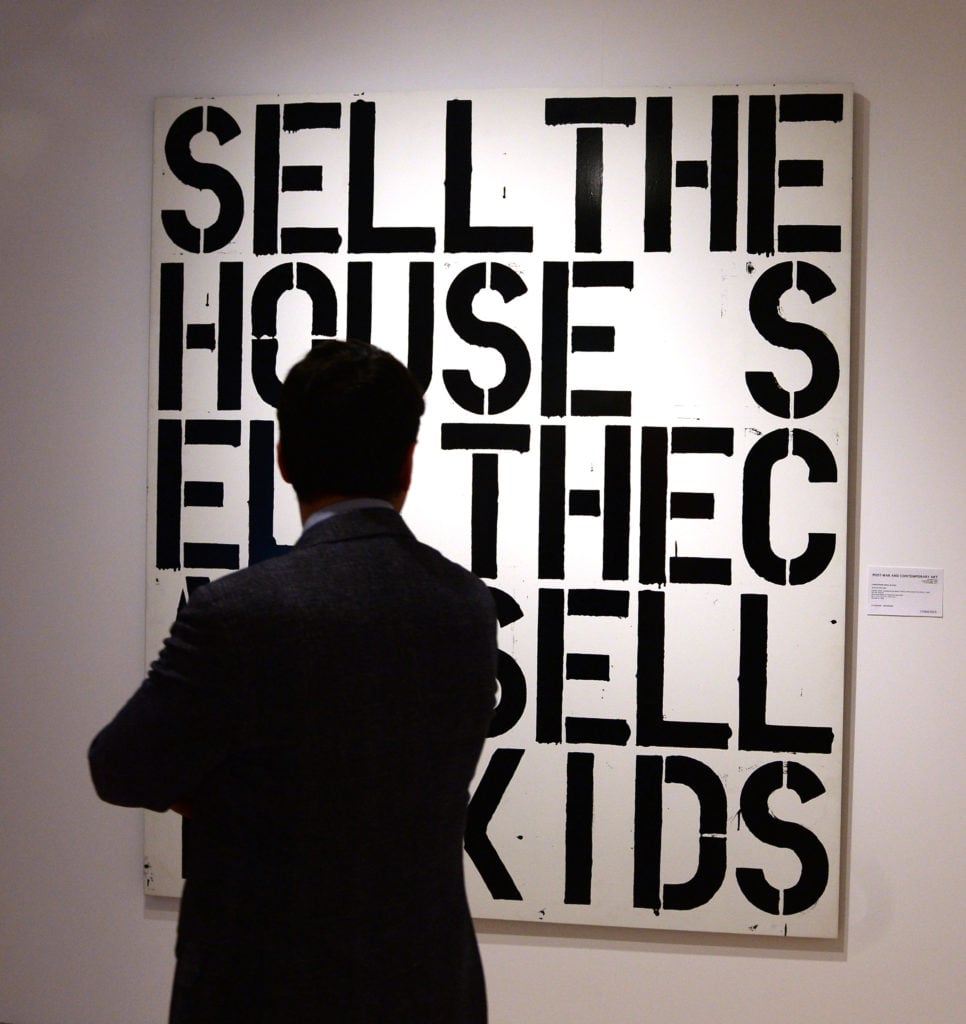

Christopher Wool’s Apocolypse Now at Christie’s. (Photo by rune hellestad/Corbis via Getty Images)

Meanwhile, a number of dealers, including P.P.O.W., Andrew Kreps, and Bortolami, have opted to relocate to Tribeca. “Chelsea just got to be too corporate for us and our identity,” P.P.O.W.’s Wendy Olsoff recently told ARTnews. “It just didn’t match anymore.” Another Chelsea stalwart, Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, will begin programming in Tribeca next month.

Still, boosters of the neighborhood maintain that Chelsea will always have a place in New York’s cultural ecosystem, even as scrappier galleries leave in droves. “The bottom line is that the buildings with multiple tenants will dwindle as residential and office buildings will take over,” says Louis Puopolo, co-head of operations at real estate firm Douglas Elliman. “Even though it will be the survival of the fittest, Chelsea will remain vibrant as a gallery district.”