Art Fairs

Despite a Booming Local Art Scene, Mexico City’s Flagship Fair, Zona Maco, Sees Sales Fizzle

The fair's return to the Centro Citibanamex was not quite a return to form.

The fair's return to the Centro Citibanamex was not quite a return to form.

Caroline Elbaor

Having squeaked past a problematic pandemic year in 2021 with a scaled-down, strictly local presentation, Zona Maco, which bills itself as the largest art fair in Latin America, returned to the Centro Citibanamex convention center February 9–13. But the fair’s 18th edition, which welcomed more than 200 galleries from 26 countries spanning the Americas, Europe, and Asia, was ultimately an unsteady return, plagued by wide disparities in sales from one gallery to another.

For all its emphasis on international significance, this year’s iteration, which welcomed 57,000 visitors, was largely a local affair, attracting primarily Mexican collectors and resulting in Mexico City-based galleries reporting the strongest sales and overall positive experiences.

The aisles at Zona Maco, held February 9–13 at the Centro Citibanamex in Mexico City. Courtesy of Zona Maco.

“This fair is a very important fair for us as a local gallery,” Polina Stroganova, director and senior partner at Proyectos Monclova, told Artnet News. “Being locals, the fair gives us the possibility to make a statement presentation with works that we would not be able to feature in fairs abroad due to logistics.”

In addition to hosting the winning work for the sponsored Tequila 1800 prize, Yoshua Okón’s Elephant (2019), Proyectos Monclova sold works by Helen Escobedo, Néstor Jiménez, Gabriel de la Mora, Hilda Palafox, Gustavo Pérez, and Eduardo Terrazas. “This year we felt a little less attendance from abroad, but certainly a very good presence from major local collectors,” Stroganova added.

Néstor Jiménez, Una sólida muralla que nos separa de la ilustración, from the series “Ojalá mueran todos” (2021), presented by Proyectos Monclova, Mexico City. Courtesy of Proyectos Monclova.

Galería RGR, also of Mexico City, partnered with Koenig Galerie of London and Berlin for a joint presentation to show artists including Alicja Kwade and Patrick Hamilton from their respective programs; through this collaboration, a representative from Koenig said they hoped to tap into RGR’s established collector base but declined to reveal any sales.

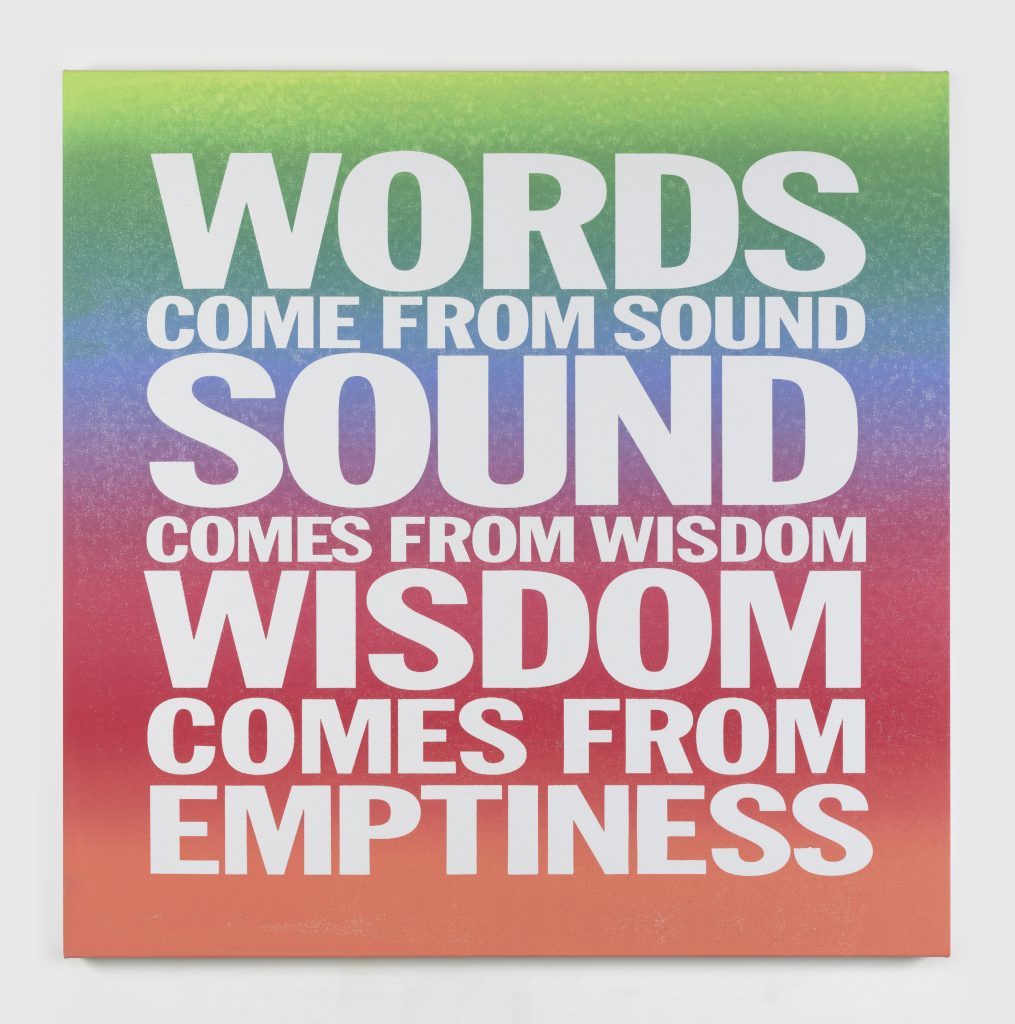

Morán Morán, originally based in Los Angeles, just opened an additional space in the Polanco district of Mexico City and was on hand with works by Diana Al-Hadid, John Giorno, Luis Gispert, Robert Mapplethorpe, Anders Ruhwald, and SoiL Thornton. “The city has a great museum and collector community,” director David Daniels explained. “Plus, we have clients from here, and it was just a good opportunity for Morán: we did the first Mapplethorpe exhibition in Mexico. We can bring artists to Mexico City that don’t get seen here, so it’s a good opportunity to expand the audience, but also to bring something new to town.”

Yoshua Okón, Elephant (2019), presented by Proyectos Monclova, Mexico City, won the Tequila 1800 prize. Courtesy of Proyectos Monclova.

Other international gallerists cited the need to forge new relationships as their primary draw. “I want to leave a lot of art here in Mexico,” said Deborah McLeod, senior director of Gagosian Los Angeles, which returned to Zona Maco after a three-year absence. “Yeah. This is why I’m here,” she went on. “I want to meet new collectors.”

The powerhouse gallery brought a roster of artists, including Michael Craig-Martin, John Currin, Rachel Feinstein, Helen Frankenthaler, Jennifer Guidi, Spencer Sweeney, and Rachel Whiteread—all of whom were making their Zona Maco debuts in hopes of gathering local exposure.

But when asked about the state of sales at the booth of one U.S. gallery, the dealer soberly shook his head before miming a knife being drawn across his throat. Both gestures sidestepped the typical euphemisms galleries issue when sales are weak, the benign language of which is always a telltale sign.

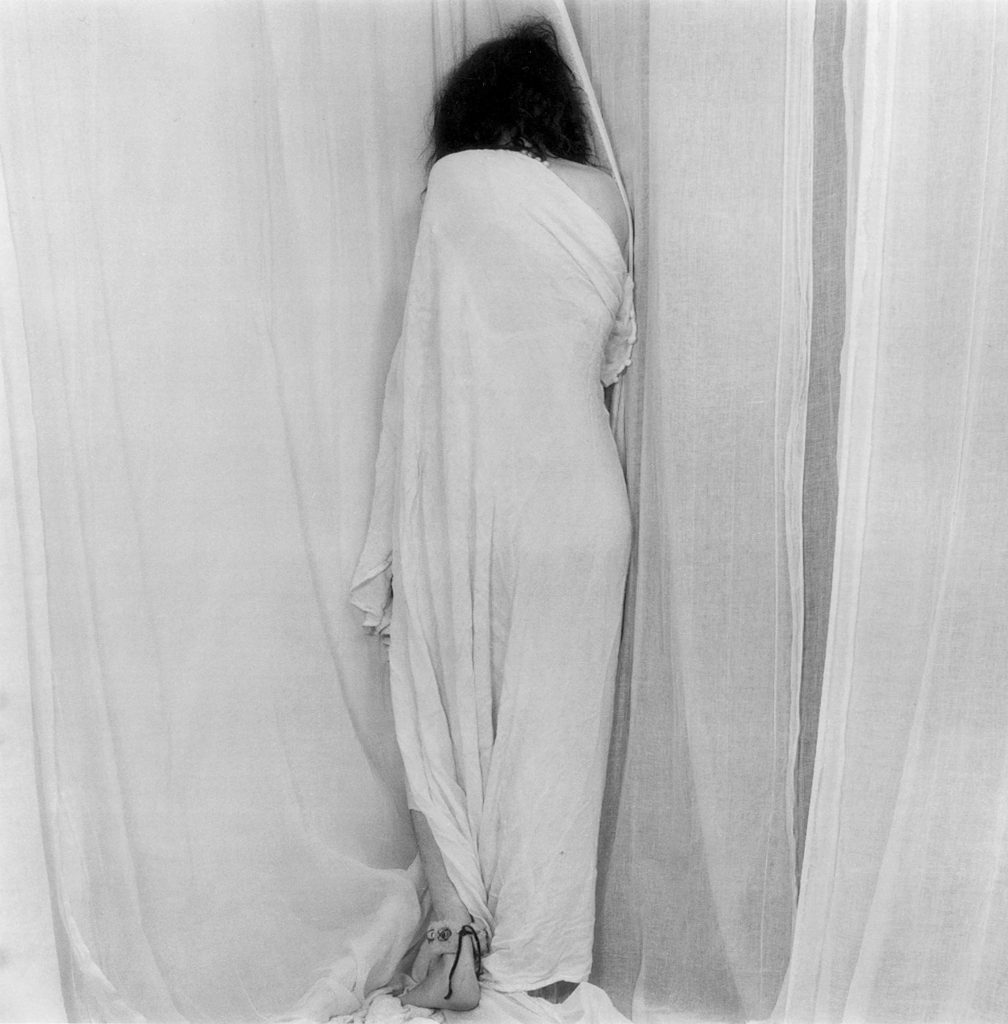

Robert Mapplethorpe, Patti Smith (1978). Courtesy of Morán Morán, Los Angeles and Mexico City.

Throughout, an underlying sense of frustration permeated this year’s fair, due in large part to the shoddy wi-fi disrupting smooth communication in the sales process. Fair-wide wi-fi does not exist: instead, exhibitors must purchase a code for use during the fair, with the price increasing per user. Fair visitors simply have no option at all.

Despite gallerists having shelled out the required additional expenses for internet access, the wi-fi nevertheless presented significant issues. Nearly every exhibitor mentioned the complication in some form; no gallery I requested images from was able to do so from the fair venue, instead having to send from other locations after hours.

At one point, when speaking with a dealer from Kurimanzutto, I asked for a checklist to be sent in real time. Because she could not do so, she noted how “strange this fair in particular is” for its seeming inability to arrange for proper internet access.

Another exhibitor, speaking on the condition of anonymity, explained: “It’s a known fact that there has never been good wi-fi in this fair.” In order to efficiently conduct business, she spoke with organizers, and as a result, was granted free internet access on an extra device. That luxury, however, was withheld from others, suggesting that the wi-fi pricing was determined not by infrastructure but profit motive.

John Giorno, WORDS COME FROM SOUND SOUND COMES FROM WISDOM WISDOM COMES FROM EMPTINESS (2015). Courtesy of Morán Morán, Los Angeles and Mexico City.

An additional exhibitor, who hails from Mexico City, implied that many gallerists end up using their own personal phone data while manning their booths. “We are not as much affected, being local,” she said. “The absence of proper Wi-Fi for visitors is not ideal, and we have forwarded this concern to the organizers.”

When asked for comment, a Zona Maco representative stated: “Wi-fi service is provided and charged directly by Centro Citibanamex convention centers.”

Despite these setbacks, the fair occupies an important calendar slot just before Frieze Los Angeles (February 17–20), and Mexico City itself remains a major destination for artists and collectors, having managed to sustain a contemporary art boom that began before the pandemic.

As a Galería RGR dealer described, “Mexico City is back to form, with all the galleries doing killer shows that are super strong, super hot. The market started coming back again, after the dip that began in March 2020, we started to see momentum building in April 2021. The city is back.”