Auctions

Artist Pension Trust Pulls 18 Lots From Sotheby’s Following Mass Artist Freakout

The sudden withdrawal throws investment model into question.

The sudden withdrawal throws investment model into question.

Eileen Kinsella

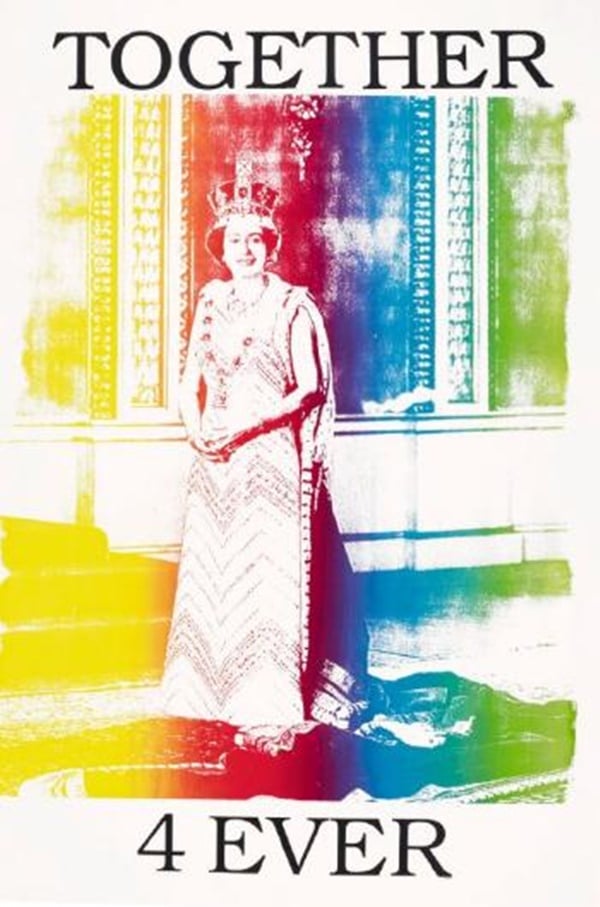

Call it a case of “the perils of blatantly treating art as an investment vehicle.” The Artist Pension Trust (APT), an entity formed with the goal of pooling work by many artists as a way to provide them future financial security, has yanked a total of 18 lots from a planned contemporary art sale at Sotheby’s. The move evidently came after complaints by the artists and galleries involved, and thereby puts a question mark over the ability of APT to manage its fund as it chooses.

All together, the works had an estimated value of up to £200,000 ($253,000).

The news was first reported in the Telegraph by Colin Gleadell. The lots, which were withdrawn from Sotheby’s “Contemporary Curated” sale in London, included work by David Shrigley, Jeremy Deller, Richard Wright, Jane and Louise Wilson, Liam Gillick, Martin Boyce, and Douglas Gordon—all Turner Prize nominees or winners—as well as by Ryan Gander, and Bob and Roberta Smith (aka Patrick Brill).

Another work by Deller that was not labeled “Artist Pension Trust” did sell at the “Contemporary Curated” sale—albeit for less than half of its modest asking price £1,500-2,000 estimate.

The website for Sotheby’s April 12 Contemporary Curated sale in London.

Sotheby’s did not immediately respond to artnet News’s request for comment, but blocks of lots are now missing from the auction house’s website.

It remains unclear whether APT or its respective artists were forced to pay withdrawal or penalty fees for removing the works from the sale.

“We had conversations with some of the artists, and the closer the auction got, the more the artists and their galleries said that auction was not in their best interests,” Al Brenner, CEO of the new MutualArt Group, the result of a recent merger of MutualArt and Artist Pension Trust, told the Telegraph. Brenner added that some of the artists’ respective galleries “said they could get better prices.”

According to Gleadell, gallerists left out of the initial process “are clearly looking to re-establish control, but whether they would be prepared to accept the agreed split, giving 60 per cent to APT and the other artists in the pool is another matter.”

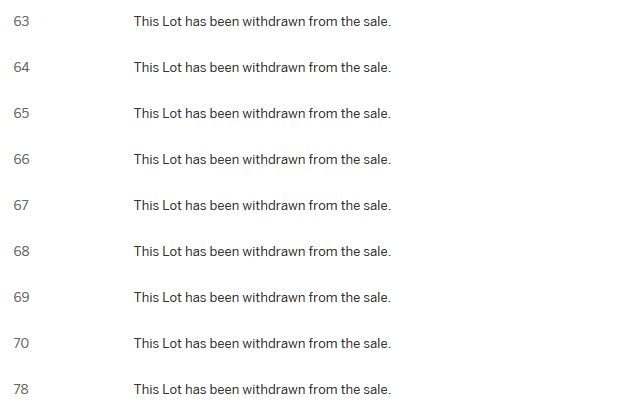

Artist Pension Trust founder Moti Shniberg.

Photo: © 2014 Patrick McMullan Company, Inc.

APT was founded nearly a decade ago by Moti Shniberg with the goal of offering “long-term financial security and international exposure to select artists around the world based on a unique tailor-made financial mode,” according to its website. (A serial entrepreneur, Shniberg is infamous for having filed a trademark claim on “September 11, 2001” on the afternoon of September 11, 2001.)

The idea is for participating artists to contribute work to the trust, which is then carefully sold off over the course of later years to raise funds that are pooled and eventually distributed to participating artists. According to APT, it has amassed what amounts to the largest global collection of contemporary art, comprising 13,000 artworks from 2,000 select artists in 75 different countries. Further, they aim to add some 2,000 works a year, growing to a total of 40,000.

The first sales from the trove took place last year. Since then, over 60 works have sold for approximately $1.2 million, most of them as private sales. Hoping to fetch higher prices, the trust started auctioning works last month, putting 15 works into a Sotheby’s sale in New York, prominently advertising them as “First-Ever Auction of Artworks from Artist Pension Trust.” All but two APT lots were sold at that time.

The APT endeavor has been closely watched as one of the most high-profile examples of the financialization of art, and is considered to be fraught with difficulties, and its control, or lack thereof, of sale “timing” was always one (see Bloomberg’s report, “The Problem With Selling the Largest Private Art Collection in the World,” from 2014.)

The withdrawal from auction indicates that APT is actually listening to its member artists’ concerns over disposing of their works at auction. It does, however, raise questions about what the artists thought they were signing on for in the first place when they agreed to contribute work with the knowledge that the ultimate goal is very specifically a sale to raise cash.

As Gleadell points out, “the reluctance of artists to sell at auction highlights why financial models are difficult to apply to art.”

Brenner told the Telegraph he is not planning more auctions, though “it might be a different story in Asia where artists are much more auction friendly.”